Population projections: recipes for

action, or inaction?

Jane N. O’Sullivan

Dr O’Sullivan is Honorary Senior

Research Fellow at the School of Agriculture and Food Sciences, University of

Queensland.

j.osullivan@uq.edu.au

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

DOI: 10.3197/jps.2016.1.1.45

Licensing: This article is Open Access (CC BY 4.0).

How to Cite:

O’Sullivan, J.N. 2016. 'Population projections: recipes for action, or inaction?'. The Journal of Population and Sustainability 1(1): 45–57.

https://doi.org/10.3197/jps.2016.1.1.45

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Introduction

Population projections, for the world

or for individual countries, are often cited as context for discussions of the

future. The most commonly cited projections are those of the Population

Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs

(UNDESA) (2016), but some, including the International Panel on Climate Change

(IPCC) socioeconomic pathways, use projections from the International Institute

for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) (2007).

From food, water and energy security

to the strength of the workforce, population projections contribute to the

landscape against which various scenarios are played out. Yet oddly, despite

the unreliability of past projections, current projections are usually taken as

immoveable fact in such analyses. The scenarios tested rarely include any

alternative population paths, and even more rarely consider that any policies

or programme options might influence the population path. Where alternative

paths are considered, such as the IPCC scenarios, they are viewed as outcomes

of socioeconomic pathways, not as determinants of those pathways.

An analogy may be the role of day

length in the yield of solar energy. There is an unquestionable link, but

because we can’t alter day length, it is not a variable that is given any

consideration in analysis of renewable energy options. It is there in the

technical calculations, but not in the discussion of determinants or strategic

implications. So it is with population, in most treatment of future challenges

and opportunities.

Cognitive Dissonance: The Fixed Point

That Keeps Moving

Last July, the United Nations

announced their 2015 global population projections to a near-empty room. A few

brief news items dutifully reported that the new estimate for the year 2100 was

11.2 billion people.

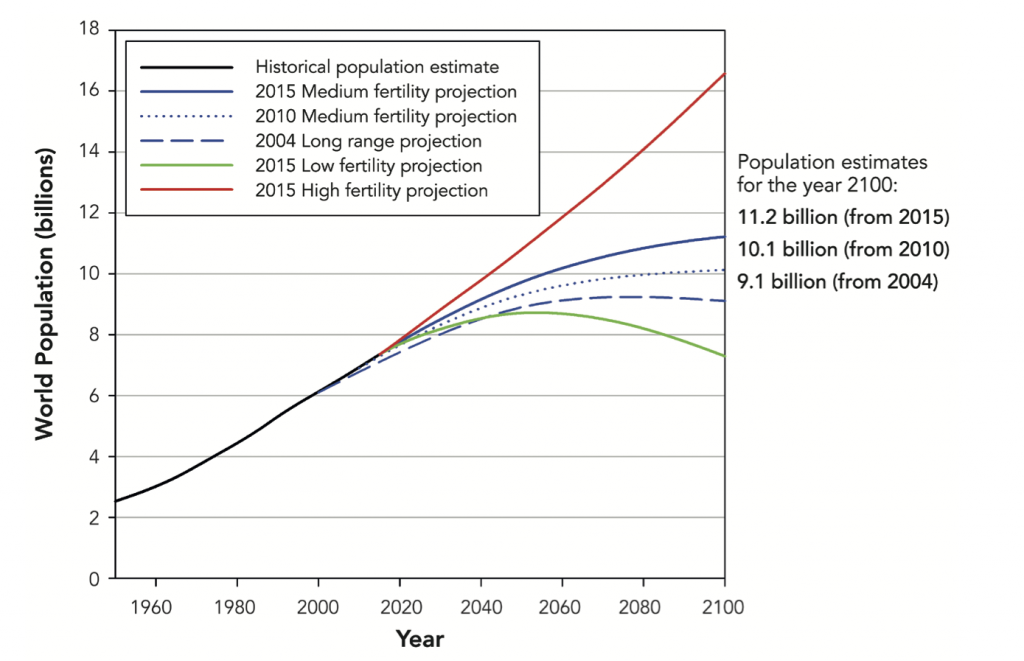

Nobody mentioned that this was more

than a billion higher than the UN’s 2010 projection, only five years ago, which

was already a billion higher than its 2004 forecast (Figure 1). Nobody

speculated how much higher it might be revised before we actually get to the

end of the century. Nobody questioned why upward revisions have become a

regular occurrence. Since 2002, each UN projection has been higher than the

last.

Figure 1. The United Nations population

projections, estimated in the 2010 and 2015 revisions (UNDESA 2011). Prior to

2010, the projections in the UN’s World Population Prospects series only

extended to 2050, but a long-range forecast in 2004 gave estimates to 2300

(UNDESA 2004).

What does this tell us about where

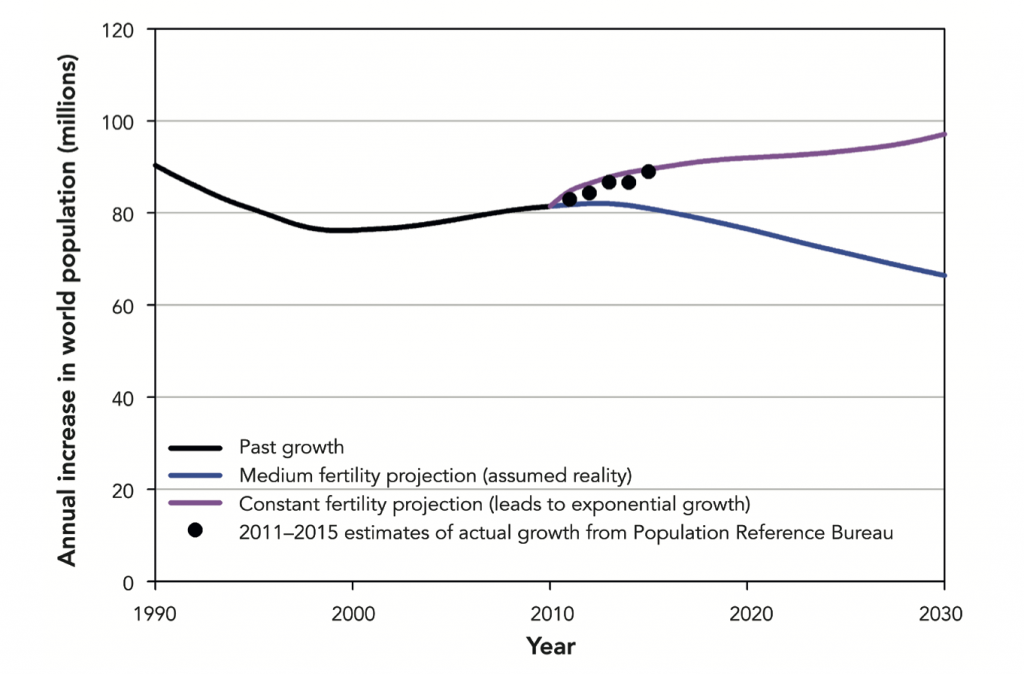

the global population is heading? Over short periods of time, trends are more

visible in the annual change in population, rather than the population itself

(Figure 2). Through the 1990s, the human population increased by a smaller

number each year, building belief that peak population was on the way. But from

2000, the increment started rising again. The UN’s medium fertility projection

expects the downward trend will resume forthwith, but annual tallies of actual

population increase, published in the Population Reference Bureau’s ‘World

Population Data Sheet’ (2015), have recorded increments well above the last

medium projection. The 2015 edition already raises the UN’s new year-2050

number to over 9.8 billion – having increased this estimate each year for quite

some time. Should we now believe they’ve got it right?

Figure 2. How have we tracked since the

last projection? The annual increment of global population from 1990 to 2010

(black), and those projected in the UN’s 2012 revision of the medium fertility

projection (blue) and the constant fertility projection (pink) (UNDESA 2013).

The latter, in which each country’s fertility is held constant, grows to reach

28 billion in 2100 (unless checked by famine and war). Superimposed are the

estimates of actual increase from the Population Reference Bureau’s annual

World Population Data Sheets, from 2011 to 2015.

Indeed, these annual increments have

been closer to a projection based on no change in national fertility rates.

This ‘constant fertility’ projection would reach 28 billion this century if not

checked by catastrophic mortality.

It is sobering to reflect what such a

check would involve. It would require approximately 100 million extra premature

deaths per year, every year for decades, to bring down the global population

through more deaths rather than fewer births. In contrast, the recent Ebola

epidemic killed around 10 thousand people. The AIDS epidemic has killed around

40 million over 30 years. Since a population of 28 billion is extremely

unlikely to be supported by Earth’s resources, catastrophic mortality is the

path we are currently choosing.

The Projections Don’t Match Reality

The UN’s medium fertility projection

has been based on an assumption that all high fertility countries will progress

steadily to below two children per woman. On release of the 2012 revision,

director of the UN’s Population Division, John Wilmoth, noted that recent falls

had been lower than expected, but the projections continue to be on the same

basis as before. He concluded,

The medium‐variant projection is thus an

expression of what should be possible … [it] could require additional

substantial efforts to make it possible. (emphasis in the original)

(2013 p. 1)

The UN’s projections expect all

countries to follow a similar smooth S-curve shape of fertility transition, if

at different rates (Raftery et al. 2012). The main reason that the projections

keep being revised upward is that a lot of countries are not following this

story-line. Since the mid-1990s, fertility declines in most mid-transition

African and Asian countries slowed or stalled. This has been attributed to a

marked decline in international support for family planning programmes (Sinding

2009). Bongaarts found that “among countries in [fertility] transition, more

than half are in a stall” (2008 p. 109) A number of countries, including

Indonesia, Egypt, Algeria, Kazakhstan, have seen fertility rebound to a higher

level. Several sub-Saharan countries have not really begun to decline. These

realities are not possibilities in the model used for projections.

A few high-fertility countries, like

Rwanda, Ethiopia and Malawi, are now tracking downwards faster than anticipated

by the UN. They may seem unlikely candidates on the basis of the most

often-cited drivers, such as wealth, women’s education and industrialisation.

But in each case, there have been conspicuous recent efforts from both

governments and NGOs to address population pressure through family planning

programmes and women’s empowerment (USAid 2012; PHE Ethiopia Consortium 2016).

Like the family-planning adopting countries of the 1970s and 80s, they are

finding that deliberate interventions to engage communities and increase access

and acceptability of contraception can be highly effective, despite low levels

of wealth and education.

Yet this good-news story is missing

from the UN’s commentary. Instead we are given a fatalistic view. Indeed, the

latest communications from the UN make no reference to ‘additional efforts’. It

presents the medium projection as the most likely “based on an implicit

assumption of a continuation of existing policies” (Gerland et al. 2014 p. 2).

What We Measure Limits What We Do

This fatalism infects most efforts to

anticipate the future. As mentioned above, a wide range of studies use the UN’s

population projections as the multiplier of human demands and impacts, when

testing which policy options might maximise future prospects. By choosing not

to vary population pathways, they provide no advice on the benefit or otherwise

of addressing population growth. Indeed, they rarely discuss population growth

as a factor affecting outcomes.

There are rare exceptions, and their

findings are salient. O’Neill et al. (2010) estimated the difference in

projected greenhouse gas emissions between scenarios assuming UN’s medium

population projection and those assuming the low projection, taking account of

impacts of changing age structure, household size and urbanization. They concluded

that achieving the low population projection could provide 16-29% of the

emissions reductions needed by 2050, and could reduce fossil fuel demand by

37-41% by the end of the century. In a recent study, Bajželj and co-workers

(2014) found that greenhouse gas emissions from the food system were sensitive

to population outcomes by a factor of 1.9, meaning that 10% higher population

would result in 19% more emissions from the food system, assuming the same

wealth and dietary preferences. The World Resources Institute’s exemplary

series “Creating a Sustainable Food Future” (2013) found that achieving

replacement level fertility (around two children per woman) in sub-Saharan

Africa by 2050 would spare an area of forest and savannah larger than Germany

from conversion to cropland, and in doing so save 16 Gt of carbon dioxide

emissions (Searchinger et al. 2013). The Futures Group found that a modest

acceleration in contraceptive uptake in Ethiopia could completely compensate

for the anticipated impacts of climate change on food security in 2050

(Moreland and Smith 2012).

Mathematical Complexity Doesn’t

Necessarily Improve Accuracy Of Projections

The change in rhetoric, which saw the

medium projection shift from ‘what should be possible’ to ‘the most likely’, is

linked to a methodological change. The most recent UN projections adopt a

Bayesian probabilistic methodology. This is a step up from the previous method,

in which high and low fertility projections merely assume a fertility rate 0.5

units (children per woman) higher or lower than the medium course in every

country – greatly underestimating the range of possibilities in high-fertility

countries, and exaggerating them in low-fertility countries.

The new methodology makes more

nuanced assessments of likely variation from the central (“medium”) projection,

but the medium projection itself is determined in much the same way as it was

before. It finds the average course that countries have taken in the past, from

whatever time their fertility started to fall in earnest, and presents this as

the most likely course that each high-fertility country will follow from now

on. The model forces the stereotypical S-shape of fertility transition by

encoding it as a double-logistic mathematical function, and researcher judgements

define the spread of each variable in the function.

Hence it is still a narrow

interpretation of possible futures. The mathematical form cannot accommodate

stalls and reversals in fertility decline, and the researcher assumptions do

not allow for further delays before individual countries establish a downward

trend. Nor does the formula consider as likely, the very high rates of

fertility decline that family planning countries have achieved in the past.

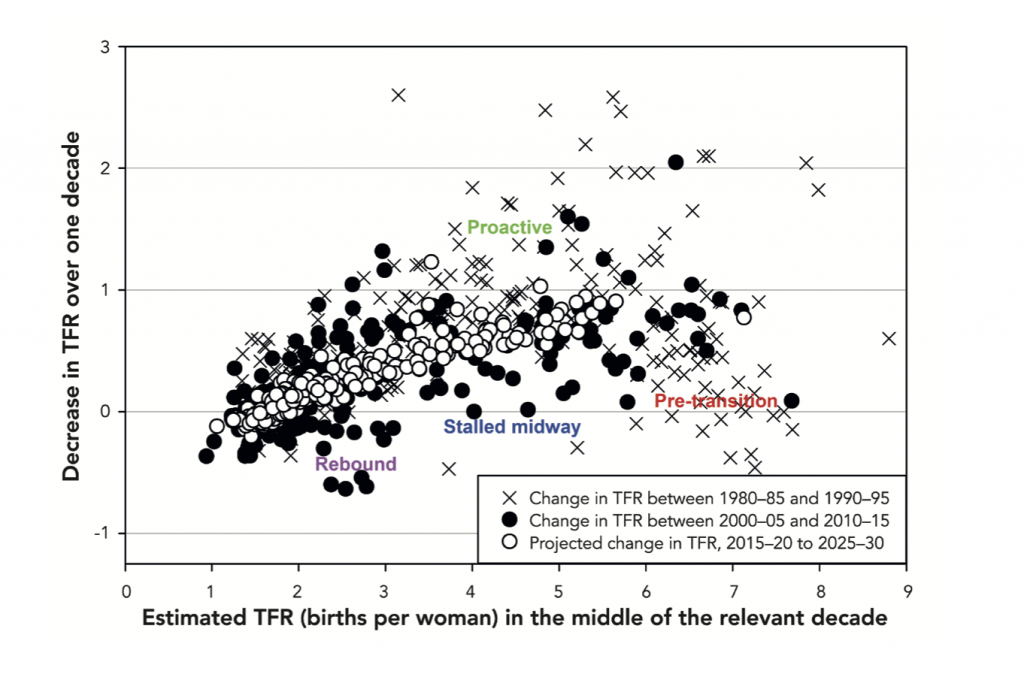

The narrowness can be seen in the

relationship between each country’s total fertility rate (TFR, average number

of live births per woman) and the rate at which it falls (Figure 3). For the

projection (open symbols), the rate of fall is tightly related to the fertility

rate. All remaining high-fertility countries are assumed to start their

fertility decline immediately and in earnest, despite their recalcitrance to

date. Data from the most recent decade (solid symbols) show much wider

diversity, with many countries falling faster, but also many near-stalled in

mid-transition or rebounding before reaching replacement level, and some have

yet to make a start. Data from the 1980s (crosses), when family planning

programmes were widely supported, show many higher rates of transition and few

stalls or rebounds.

Figure 3. The relationship between the

fertility rate of each country and the rate at which its fertility falls, for

the most recent decade (black dots), compared with the first projected decade

(open dots) and with the 1980s (crosses). Over time, the fertility of

individual countries undergoing fertility transition moves from right to left.

The projections depend on what is anticipated to be the average pathway, the

variation around that average pathway, and when each country embarks on their

transition.

History’s Lessons Unheeded

The UN’s deterministic approach to

projection overlooks the role of choices, rather than chance, in the different

paths each country has followed.

It was programme choice which saw

Thailand’s fertility fall rapidly in the 1970s, Iran’s pull abruptly away from

those of its neighbours, Costa Rica lead the pack in Central America, and

Rwanda now diverging so strongly from neighbouring Burundi and Uganda. These

choices are not being talked up by the UN. Indeed, by presenting the

projections as “probabilistic”, the impression is given that direct action is

futile. There are no policy levers attached to model, determining whether

fertility rate is higher or lower than the average – only unidentified external

factors acting randomly.

For lack of volition, most of the

highest fertility countries do not yet have fertility falls as fast as the

medium projection expects. Why, then, does the medium projection assume that

all remaining high fertility countries will commence steady fertility decline

immediately, when history tells us that these abrupt starts have depended on

policy change? Since these countries have the greatest influence on future

global population, we can only expect that the next revision will also be

upwards.

This is the crux of the matter: assuming a continuation of existing policies, the UN’s

methodology poses that it is most likely that

the highest fertility countries, which have seen the slowest fertility

reductions to date, will show the fastest reductions from now on. Moreover,

despite many mid-transition countries having stalled or increased fertility in

the past decade, it finds that none are likely to do so in the coming decade,

without any change of policy.

I am reminded of the saying, probably

wrongly attributed to Albert Einstein, that “the definition of stupidity is

doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.” By

reapplying the same model for each revision, does the UN Population Division

expect its next projection to be any more reliable than the last?

The Future Will Be Shaped By Our

Choices

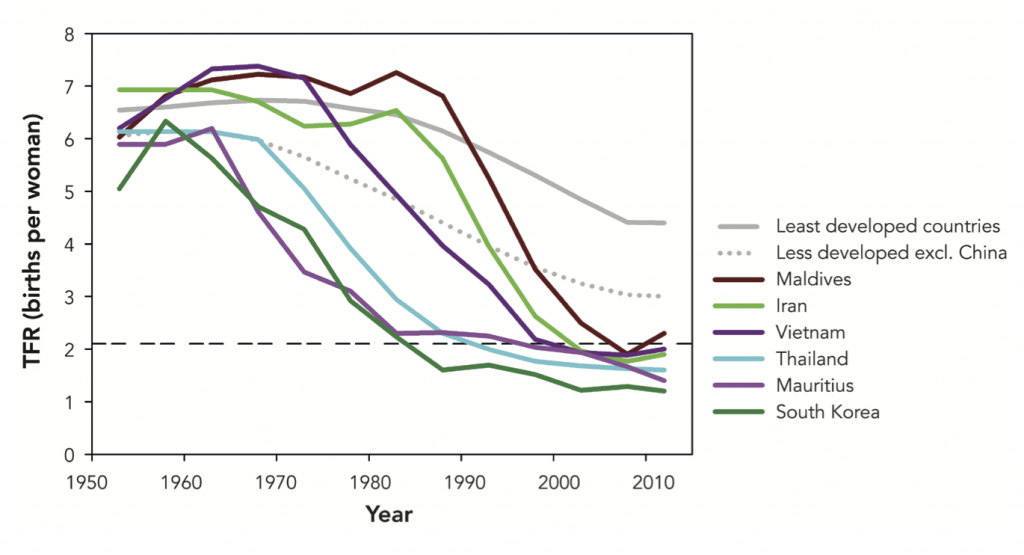

We could choose a different result,

but it would require doing things differently. Much faster fertility

transitions are possible, if family planning and small family norms are

promoted alongside women’s health and rights. Many developing countries have

successfully achieved below-replacement or near-replacement fertility in this

way. Figure 4 shows the time course of fertility for some of them. In each

case, the abrupt start to fertility decline coincided with initiation of

voluntary family planning programmes. Rates of fertility decline have been two

to three times those expected in the UN projections. No economic or educational

trigger was evident, but in each case economic development, including

improvement in educational and health outcomes, followed as a consequence of

lower population growth (O’Sullivan 2013).

Figure 4. Time course of total

fertility rate (TFR, births per woman) for selected countries which implemented

population-focused voluntary family planning programmes at differing times,

showing rapid change in fertility, compared with aggregate TFR for less

developed and least developed nations. Data from UNDESA (2011) and Population

Reference Bureau World Population Datasheet (2013).

These programmes involved providing

access to family planning information and services to all citizens, through

culturally appropriate channels. They also involved addressing barriers to

women exercising their reproductive choices, such as child marriage, women’s

access to education and economic autonomy, and attitudes of men towards women

and their roles. They did not rely on coercion, such as China’s one-child policy.

Indeed, China’s fertility decline was also driven by a voluntary family

planning programme, which preceded the one-child policy by a decade. By the

time the one-child policy was rolled out in 1979, the job was largely done.

However, over the past two decades concern about coercive fertility control has

been heightened to the extent that merely discussing the benefits of fewer

children is treated as coercive. It is assumed that access alone is sufficient,

and women will make the ‘right’ choice about family size without being given

any information on which to base that choice. Yet the main reasons given by

women for not using contraception are not related to access or affordability

(Ryerson 2010). The successful voluntary family planning programmes of the

1970s and 80s were generally characterised by widespread promotion of fewer,

more widely spaced children, and sound information about contraceptive options,

dispelling myths of their dangers.

Recently, Population Health and

Environment (PHE) programmes, which integrate family planning with livelihood,

public health and environmental management interventions, are showing that

coherent cross-sectoral programmes can greatly increase community acceptance

of, and even enthusiasm for family planning, overcoming cultural resistance

(PAI 2015). New contraception technologies, including implants and injectables,

are making family planning delivery much cheaper, more reliable and less

dependent on medical personnel. New communications technologies and more

literate populations exposed to cultures beyond their own allow information and

attitudinal change to spread more easily. These advances could mean that the

next generation of family planning programmes is even more effective than in

the past. Nor are such interventions costly: a UN study estimated that “for

every dollar spent in family planning, between two and six dollars can be saved

in interventions aimed at achieving other development goals” (UNDESA 2009 p.1).

It’s still possible for the world

population to peak under 10 billion. Each year such action is deferred

increases the achievable peak by around 100 million people. Time is of the

essence, but if political will could be rallied quickly enough, perhaps a peak

around 9 billion could yet be achieved.

Such an outcome would ease many

challenges, particularly food security, climate change mitigation and

adaptation, and biodiversity loss (Speidel et al. 2015). It could head off mass

mortality on a scale humanity has never seen. But first we have to care how

many people there will be.

Conclusion

Projections should arm us to prepare

for the future and take pre-emptive action to avoid threats. Recent population

projections have had the opposite effect. By failing to acknowledge the impact

of choices, they have undermined pre-emptive action. This fatalistic approach

has probably already contributed to a global slow-down in fertility decline

over the past two decades, which has already added billions to the likely peak

population. By giving little weight to the recent slow-down, projections have

recently over-estimated fertility decline. In turn, by presenting overly

optimistic expectations of fertility decline, they have given false reassurance

that population growth will end within decades regardless of what we do, allowing

legitimate concern about overpopulation to be dismissed as naïve and pointless

paranoia. Partly to avoid such condescension, many researchers avoid treating

population as a variable. They consequently fail to measure its profound impact

on so many of the challenges now faced by humanity and by the many other

species we are crowding out. A new narrative is urgently needed, to reinstate

the importance of population policies and programmes for human development and

environmental sustainability (Bongaarts 2016).

References

Bajželj B., Richards K.S., Allwood

J.M., Smith P., Dennis J.S., Curmi E. and Gilligan C.A. (2014) Importance of

food-demand management for climate mitigation. Nature

Climate Change 4, 924–929. http://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/v4/n10/full/nclimate2353.html

Bongaarts J. (2008) Fertility

Transitions in Developing Countries: Progress or Stagnation? Studies in Family Planning 39(2): 105–110.

IIASA (2007) Population Projections. http://www.iiasa.ac.at/web/home/research/modelsData/PopulationProjections/POP.en.html

Moreland S. and Smith E. (2012) Modeling climate change, food security and population: pilot

testing the model in Ethiopia. Futures Group. http://futuresgroup.com/files/publications/Modeling_Climate_Change_Food_Security_and_Population.pdf

O’Neill BC, Dalton M, Fuchs R, Jiang

L, Pachaui S, Zigova K (2010) Global demographic trends and future carbon

emissions. Proc Natl Acad Sci107:17521-17526.

PAI, Pathfinder International, Sierra

Club (2015) Building resilient communities: the PHE way. http://womenatthecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Building-Resilient-Communities-The-PHE-Way.pdf

PHE Ethiopia Consortium. (2016). What is PHE?. [ONLINE] Available at:http://www.phe-ethiopia.org/.

[Accessed 4 April 2016]

Population Reference Bureau (2015) 2015 World Population Datasheet.http://www.prb.org/Publications/Datasheets/2015/2015-world-population-data-sheet.aspx

Raftery, A.E., N. Li, H. Ševčíková,

P. Gerland, and G.K. Heilig. (2012) “Bayesian probabilistic population

projections for all countries.” Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences 109 (35):13915-13921. http://www.pnas.org/content/109/35/13915.full

Ryerson, W.N. (2010) Population, the

multiplier of everything else. In: The Post Carbon Reader:

Managing the 21st Century’s Sustainability Crises, Richard Heinberg

and Daniel Lerch, eds. (Healdsburg, CA: Watershed Media, 2010). http://www.postcarbonreader.com

Searchinger T., Hanson C., Waite R.,

Lipinski B., Leeson G. and Harper S. (2013) Achieving Replacement Level

Fertility. World Resources Institute working paper, Instalment

3 of “Creating a Sustainable Food Future” http://www.wri.org/publication/achieving-replacement-level-fertility

Sinding, S.W. (2009) Population,

poverty and economic development. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364:

3023-3030. http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/364/1532/3023

UNDESA (2004) World Population in 2300.http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/longrange2/2004worldpop2300reportfinalc.pdf

UNDESA (2009) What would it take to accelerate fertility decline in the least developed

countries? UN Population Division Policy Brief No. 2009/1.

UNDESA (2011) World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision. New

York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/publications/world-population-prospects-the-2010-revision.html

UNDESA (2013) World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision. New

York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/publications/world-population-prospects-the-2012-revision.html

UNDESA (2015) World Population Prospects, the 2015 Revision. New

York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/

Wilmoth, J. (2013) The 2012 Revision. Statement by Director,

Population Division Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations.

Press briefing upon publication of World Population Prospects: Thursday, 13

June 2013, UN Headquarters, New York.