Prospects for accelerated fertility decline in

Africa

John

Cleland

John

Cleland is Professor Emeritus of Medical Demography at the London School of

Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. He is a former president of the International

Union for the Scientific Study of Population, a fellow of the British Academy

and received a CBE for services to social science.

John.Cleland@lshtm.ac.uk

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

DOI: 10.3197/jps.2017.1.2.37

Licensing: This article is Open Access (CC BY 4.0).

How to Cite:

Cleland, J. 2016. 'Prospects for accelerated fertility decline in Africa '. The Journal of Population and Sustainability 1(2): 37–52.

https://doi.org/10.3197/jps.2017.1.2.37

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Abstract

The future size of world

population depends critically on what happens in sub-Saharan Africa, the one

remaining region with high fertility and rapid population growth. The United

Nations envisages a continuing slow pace of fertility change, from five births

per woman today to three by mid-century, in which case the population of the

region will increase by over one billion. However, an accelerated decline is

feasible, particularly in east Africa. The main grounds for optimism include

rising international concern and funding for family planning (after fifteen

years of neglect), and favourable shifts in the attitudes of political leaders

in Africa. The examples of Ethiopia and Rwanda show political will and

efficient programmes can stimulate rapid reproductive change.

Keywords: Africa; population projections;

fertility; desired family sizes; population policies.

Introduction

The

future of the world’s population depends on many factors that are impossible to

predict with certainty. A devastating pandemic is a distinct risk. The 1918 flu

pandemic is estimated to have killed about 4% of the world’s population. A

repetition today would imply the death of 280 million, a huge number but one

that represents only about four years of growth at current rates. Another

possibility that would have a profound impact on future population growth is a

substantial rise in China’s low birth rate in response to the ending of the

One-Child policy. But the biggest uncertainty is the future of fertility in

sub-Saharan Africa, the one remaining region with high birth rates and rapid

population growth. Compared with projections based on an assumption of a

continued gentle decline, an accelerated decline in fertility would reduce

Africa’s projected population size by 200 million by mid-century, rising to 800

million by the end of the century (Gerland, Biddlecom and Kantorova 2016).

The

central aim of this paper is to analyse the prospects for future fertility

change in sub-Saharan Africa. This will require an examination of past trends,

an attempt to understand the factors underlying the persistence of high

fertility and the conditions favourable to decline, and identification of

policies and programmes that can most effectively change the future course of

childbearing.

Projected population growth,

2015-2050

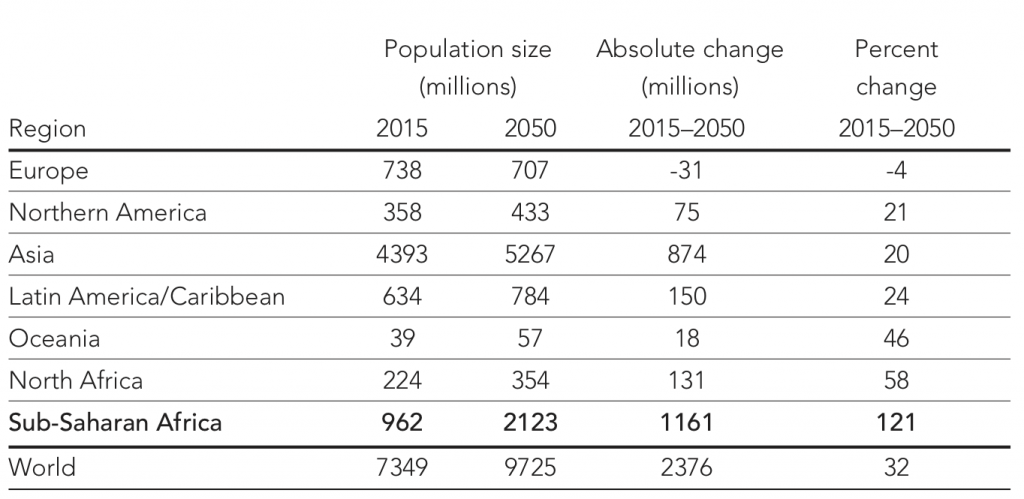

Table

1 shows the most recent medium (ie most likely) population projections up until

mid-century published in 2015 by the United Nations Population Division.

Longer-term projections exist but are highly speculative because they have to

make assumptions about the childbearing of individuals not yet born. Over a

horizon of a few decades, UN projections have a good record of predictive

validity at global and regional levels. While by no means immutable, they

deserve to be taken seriously.

Table

1 shows an expected increase in global population of 2.4 billion between 2015

and 2050. The growth comes very largely from two regions, Asia with an extra

870 million and sub-Saharan Africa with 1.2 billion. The proportionate

increases in these two regions, however, are very different. In Asia, the

projected increase is a mere 20%, about the same as expected in northern

America, largely because of assumptions of continuing in-migration, and lower

than in Latin America or north Africa. The large increment of 870 million in

Asia is mainly a reflection of that region’s huge base population size. By

contrast, the population of sub-Saharan Africa is projected to more than double

in size, an increase of 120%. Whatever happens in regions other than Asia and

sub-Saharan Africa will make precious little difference to the global total in

mid-century. Differential growth has had and will continue to have a profound

effect on the regional balance of population. In 1950, sub-Saharan Africa

accounted for only 7% of world population. By 2050, this fraction will likely

rise to 22%. Over the same 100 years, Europe’s contribution is the exact mirror

opposite, a decline from 22% to 7%.

Table 1: Population Growth,

2015-2050, by region

Source: United Nations. 2015

World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision

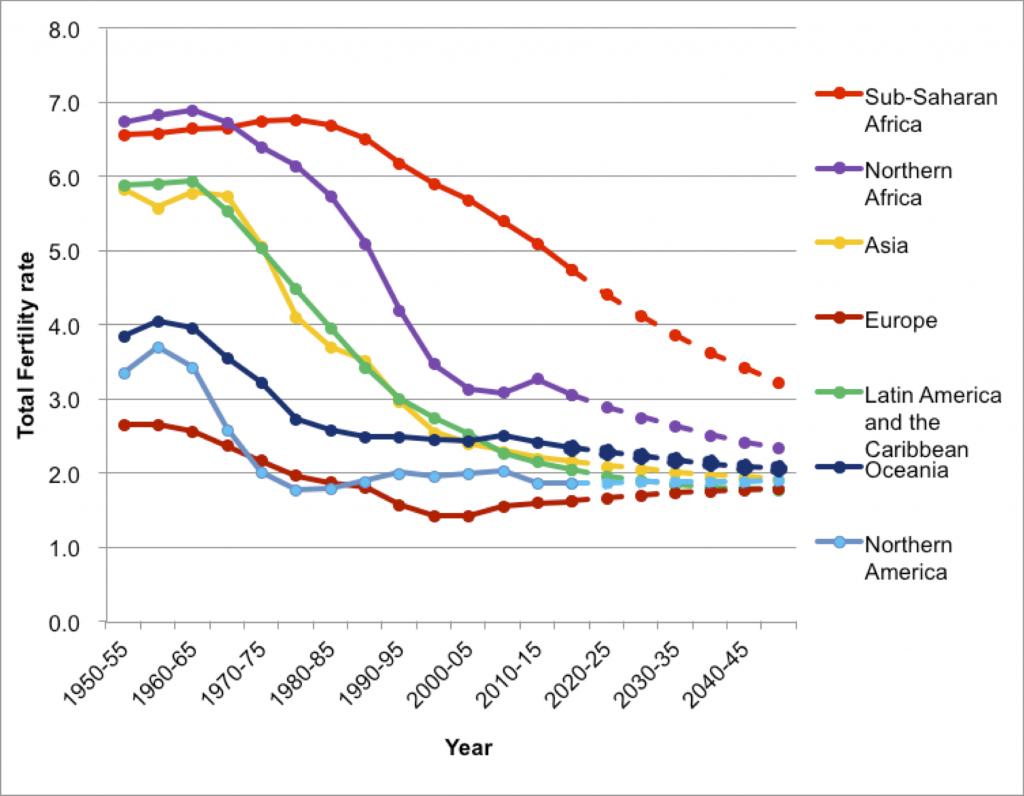

The main drivers of population growth are fertility and age

structure: the higher the proportion of population in the reproductive age

span, the higher will be the birth rate at the same level of childbearing per

woman. Figure 1 shows past and projected fertility for the same six regions as

in Table 1. In the 1950s, fertility in the four poorer regions was similar, in

the range of six to seven births per woman. In Asia and Latin America, sharp

declines started in the 1960s and fertility is now close to two births per

woman, the replacement level that in the long term ensures population

stability. Population growth continues mainly because of a conducive age

structure. In its projections the United Nations assumes a continuing fall in

fertility to below replacement. In the Arab states of north Africa the drop in

childbearing also started in the 1960s and the United Nations assumes a

continuing fertility decline, from a little over three births today to close to

replacement by mid-century. In sub-Saharan Africa, decline started later and

proceeded at a slower pace than elsewhere. The UN assumes that the gentle

decline will continue from the current level of about five to about three births

by 2050.

Figure 1: Trend of total

fertility rate by world region, 1950-2050  Source:

United Nations.2015 World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision

Source:

United Nations.2015 World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision

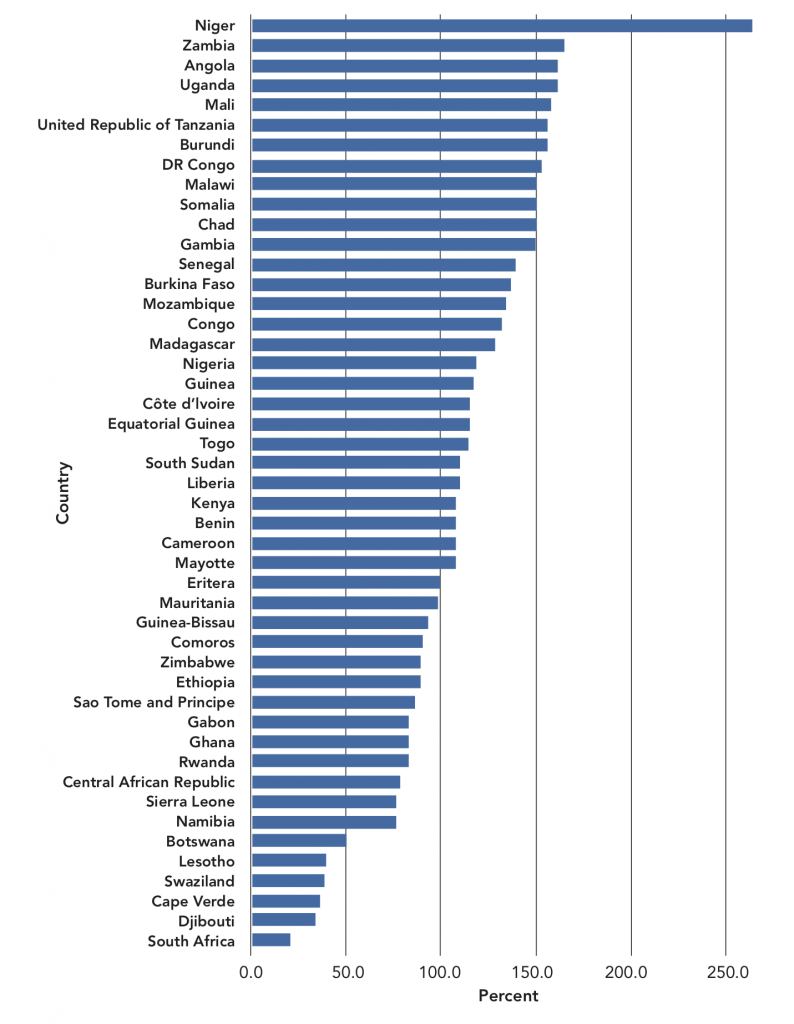

Of

course, these regional averages disguise country variations. In Asia, the main

exceptions to prevailing low fertility and population growth are Afghanistan,

Iraq and Yemen where the child-bearing level is still around four births.

Fertility also remains above three in Pakistan’s substantial population. In

sub-Saharan Africa, fertility ranges from close to replacement in the Republic

of South Africa to over seven births per woman in Niger. This variability is

expressed in Figure 2 in terms of projected percent increase in population

between 2015 and 2050. Figure 2 makes clear that most countries in Africa are

expected to experience a doubling of population, or more, in the next 35 years.

Only 11 of the 46 countries are projected to grow by appreciably less than

100%.

Figure 2: Percent increase in

population between 2015 and 2050

Source: United Nations.2015

World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision

Niger

with a projected increase of 250%, from 20 million to 72 million demands

special consideration. This is a relatively rare example of a projection that

makes no sense. Niger has a very fragile environment, highly susceptible to

climate change, and suffers periodic food crises. It is impossible to envisage

that the country can support such a growth in population, even at the most

basic standards, or that international food relief can come indefinitely to the

rescue on such a massive scale. The inevitable resolution will be mass

migration, mostly to neighbouring countries. Whether this can happen without

major strife is one of the great uncertainties but the topic is so politically

sensitive that it is ignored in international discourse. Niger is only an extreme

example of a Malthusian crisis that will affect the whole of the Sahel, the

strip of arid and semi-arid land stretching from the Atlantic to the Horn of

Africa (Potts, Henderson and Campbell 2013). As shown in Figure 2, population

projections for Mali and Chad are also very high.

Explanations for the slow

fertility decline in sub-Saharan Africa

What

distinguishes African reproductive systems most clearly from those in other

parts of the world is the stated desire for many children, expressed by both

women and men in countless surveys. The earliest surveys in Asia and Latin

America, conducted in the late 1950s and 1960s typically showed that most

couples wanted to have two to four children; many women in their 30s wanted to

stop childbearing altogether. In sub-Saharan Africa, desired family sizes were

(and remain) much larger and fewer women wanted to stop. For instance, World

Fertility Surveys, conducted in the 1970s and early 1980s, show that desired

sizes among young women in seven African countries ranged from 5.2 in Ghana to

8.3 in Senegal. By contrast, in only one (Syria) of 14 Asian and Pacific

countries did the mean desired size exceed five children. In 13 Latin American

and Caribbean countries, the highest desired size was 3.8 in Mexico

(Lightbourne 1987).

What

accounts for this huge difference in attitudes towards childbearing? Answers

can be sought in evolutionary history. Homo sapiens evolved in Africa, facilitating the

co-evolution of a uniquely wide range of parasitic diseases, leading to

exceptionally high mortality. Africa’s population is characterised by a mosaic

of different ethnicities with rather little historical evidence of large

empires that could impose eras of peaceful co-existence. Mortality was thus

further raised by incessant raiding and warfare between different tribes. These

two factors go a long way to explaining Africa’s small population size until

recently. They may also account for reproductive attitudes. Survival of the

group depended on a high birth rate and, in particular, on the ready

availability of young men to protect against aggressive neighbours.

The

speculations in the preceding paragraph are consistent with more commonly

expressed explanations. John Caldwell has argued forcefully that features of

social organisation, underpinned by traditional African religion, served to

engender and sustain pronatalism (Caldwell and Caldwell 1987; Caldwell,

Orubuloye, and Caldwell 1992). Drawing on anthropology and his own extensive

field studies in Nigeria, Caldwell viewed the extended lineage, rather than the

nuclear family, as the key feature of social organisation. The lineage includes

both the living and the dead. The dead retain their individuality for as long

as they are specifically remembered and may be reborn into the lineage. The imperative

for both living and dead is survival of the lineage. Reproduction is enforced

with spiritual power and reproductive failure is interpreted as ancestral

disapproval.

The

dominance of the lineage also has more prosaic economic implications. Mortality

decline invariably precedes drops in fertility and, as a consequence, the

number of children who survive to adulthood rises. Whereas in Asia, the burden

of rearing an increasing number of surviving children fell directly on the

nuclear parents, in Africa the burden is diffused among relatives. More

affluent lineage members are under an obligation to help those less fortunate

with, for example, school fees. Child fostering is common. A related factor

concerns land tenure in much of Africa, which is controlled by communities and

allocated to individuals according to need. These features are likely to delay

a fertility response to improving survival.

Other

commentators have sought to account for the slow decline in fertility more

straightforwardly in terms of low socio-economic development. All the familiar

indicators—life expectancy, GDP per head, percent urban and educational level—

are less favourable in Africa than elsewhere. A recent examination suggest that

the level of development at the start of the African fertility transition in

the 1990s was lower than in other developing regions at the start of their

transition in the 1970s (Bongaarts 2016). Nevertheless, at the same level of

development, fertility in African countries is about one birth higher than

elsewhere. In other words, there is a unique “Africa” effect on childbearing.

Yet a

further explanation is the relative lack of firm policies and programmes to

reduce rapid population growth by promotion of contraception. Opinion is

divided about the effectiveness of family planning programmes to reduce

fertility. Most economists are sceptical and view demand for smaller families

stemming from modernisation as the overridingly important factor. But they

ignore the fact that contraceptive practice represents a radical innovation

that concerns core features of human life—sex and procreation. Like most such

innovations, contraception is often greeted with deep suspicion and anxiety and

sometimes with outright hostility. Information and educational efforts, together

with family planning services, organised by governments or large

non-governmental organisations, can allay suspicion and subdue opposition and

thereby hasten mass adoption of contraception and fertility decline. Strong

government actions were a major influence on fertility transition in Asia,

though less so in Latin America where initiatives were spearheaded by

non-government organisations such as Profamilia in Colombia and Bemfam in

Brazil.

Until

recently, the attitude of African political leaders to the idea of fertility

reduction and curbing population growth has been lukewarm or hostile, no doubt

in part because of the perception by leaders that most citizens wanted large

families (May 2016). Few governments have launched major family planning initiatives.

The main exceptions have been South Africa under the Apartheid regime, Rhodesia

(now Zimbabwe) under the illegal Smith regime and Kenya in the 1980s under

President Moi; it is no coincidence that these three countries have been at the

forefront of reproductive change in Africa.

Prospects for accelerated

fertility declines

The

UN medium projections, thus far, have been used to portray the most likely

future for Africa’s fertility trend and population growth. But, as already

mentioned, they are not set in stone. In this section, future fertility

prospects are assessed in three very different ways: trends in the desire to

stop childbearing; the reproduction of the best educated; and the lessons from

two countries that have achieved recent rapid declines.

Desire to stop childbearing

In

Asia, Latin America, and north Africa, the fall in childbearing was dominated

by family size limitation. Couples, typically in their early 30s, having had a

few children, decided that they wanted no more and adopted contraception to

achieve this desire. Some evidence suggests that the African fertility

transition is taking, and will continue to take, a very different form. Rather

than contemplating a permanent cessation of childbearing, it is suggested that

couples will postpone births and reduce ultimate family size by very long

inter-birth intervals (Moultrie, Sayi and Timaeus 2012). Such behaviour is

consistent with a large and convincing body of evidence that wide birth spacing

has long been valued in Africa and indeed has an important role in enhancing

child growth and survival. Historically it was achieved by prolonged postnatal

sexual abstinence.

Nevertheless,

it seems unlikely that low fertility will be achieved in Africa solely by

postponement and spacing. Women start families at an early age and, even with

average inter-birth intervals of 48 months, five children can be achieved with

ease. It is also telling that prospective studies in Nigeria, Ghana, Malawi and

work in progress in Kenya show that women or couples who state at baseline that

they want no more children do indeed achieve lower fertility in the subsequent

two or three years than those who state a desire for more children at some time

in the future. In rural North Malawi, for instance, 33% of women who stated

that they wanted no more children gave birth or became pregnant within the next

three years compared with 55% of those who wished to delay the next child by

three or more years and 63% of those who wanted a child within three years

(Machiyama et al. 2015). The proportion of those wishing to stop who

nevertheless became pregnant may seem large but similar results have been

obtained in Asia and north Africa and many possible explanations can be found:

change of preference; contrary desires of the husband; and contraceptive

failure, discontinuation or avoidance. The significance of the Malawi results

is that the family size limitation appears to provide a more compelling motive

for pregnancy-avoidance than postponement. Perhaps, after all, the pattern of African

reproductive decline will not be so different from that in other regions.

To

the extent that the spread of family size limitation is essential for the goal

of low fertility, it becomes relevant to examine trends in the desire to stop

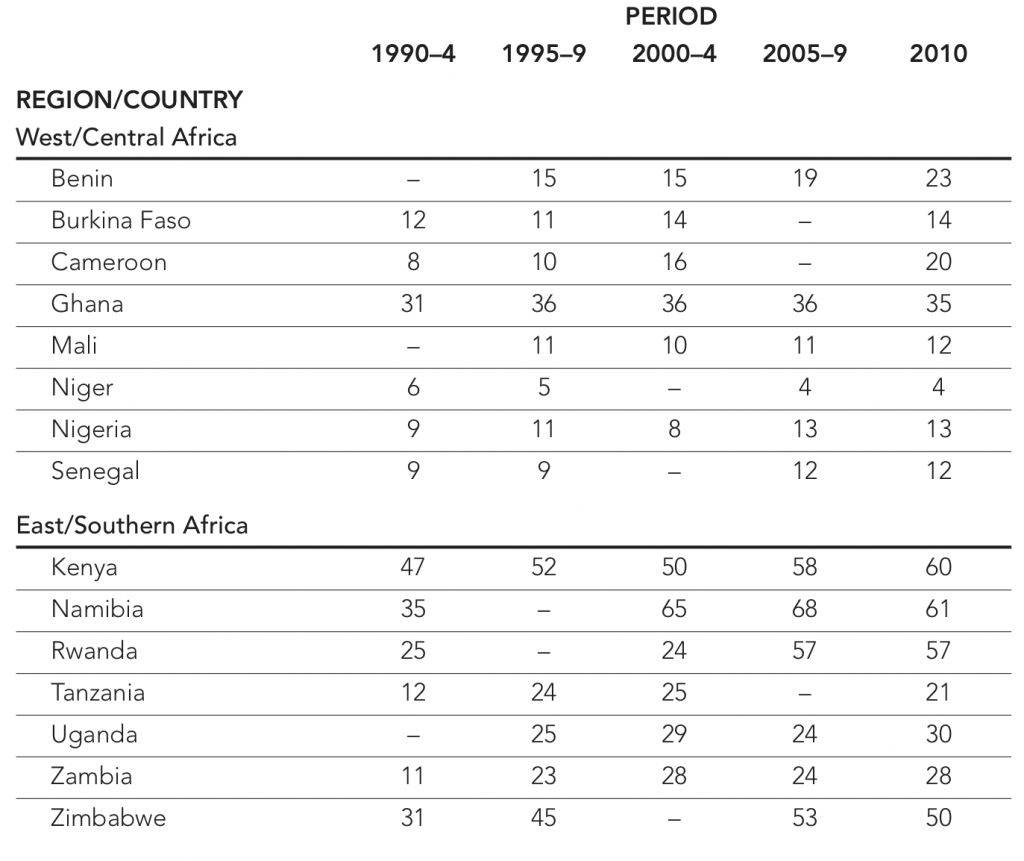

having any more children. Table 2 shows these trends for women who already have

three surviving children. The choice of three children is in part arbitrary but

also justifiable on the grounds that low fertility is unlikely until a large

fraction of couples are content to have a small family of three or fewer

offspring. Countries with at least four Demographic and Health Surveys have

been chosen for this analysis.

Table 2: Among women with three

living children, percentage who want no more

The

trends for west and central Africa are depressing in terms of prospects for

decline. In most countries, only a small minority of women wish to stop

childbearing after three children and trends over the past 20 years are modest.

Cameroon is a partial exception, with an increase from 8% to 20% between the

early 1990s and recent years. Ghana, the forerunner of fertility decline in

this sub-region, has a much larger proportion wishing to cease childbearing

though little change has occurred in the past two decades.

In

east and southern Africa, the impression is very different. In four of the

seven countries, half or more of women with three children express contentment

with this number. The exceptions are Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. In both

Tanzania and Zambia, a sharp rise from around 12 to 24% is apparent in the

1990s but there has been little further change since then.

Kenya

is a particularly interesting case. In the World Fertility Survey of 1979-80,

only 16% of all married women wanted no more children but within a decade this

proportion had swelled to 49%. This decade saw the implementation of a vigorous

family planning programme, with a strong informational and educational

component, led by President Moi and Vice-President Kibaki, and a surge in

contraceptive adoption. This sequence suggests that reproductive aspirations

can be abruptly de-stabilised by the advent of reproductive choice. Something

similar may have occurred in Rwanda. In this country the dramatic rise in the

percent wishing to stop at three children in the first decade of this century

coincided with a major re-invigoration of family planning under the auspices of

President Kagame. However, puzzles remain. In Zambia, use of a modern

contraceptive method rose sharply from about 20% in 2000 to 45% in 2013, about

the same level of use as in Rwanda, but without the revolution in reproductive

attitudes.

The

broad conclusion from this examination of reproductive preferences is that the

idea of family size limitation has taken root in much of east and southern

Africa and the prospects of further declines look bright. The opposite applies

to west and central Africa.

Fertility among well educated

women

The

reason for attempting to discern the future by examining current levels of

childbearing among well educated women is that they are usually in the vanguard

of change. Contraceptive adoption and a fall in fertility usually starts in

privileged strata before diffusing more widely. Thus the reproduction of women

with secondary or higher schooling in Africa may be a guide to behaviour in the

total population in the next couple of decades.

A

total of 13 west or central Africa countries have conducted Demographic and

Health Surveys, or similar, in 2010 or more recently. The percent of women aged

15-49 years with some secondary or higher education ranges from 9% in Niger to

63% in Ghana, with a mean of 29%. Among this group, the lowest fertility is

recorded in Cote d’Ivoire at 2.8 births. Fertility of over 4.0 is apparent in

Niger (5.0), Mali (4.6), Nigeria (4.5) and Gambia (4.5). The mean for all 13

countries is 3.8.

In

east and southern Africa the percent of well educated women ranges from 11% in

Ethiopia to 73% in Zimbabwe, with a mean among 11 countries of 31%. In this

group the highest fertility is found in Burundi (4.6) and Uganda (4.5) and the

lowest in Ethiopia (1.9). Mean fertility is 3.5 births.

Several

observations may be made on the basis of this simple exploration. First,

achievement of secondary schooling does not automatically translate into low

fertility as evidenced in seven of these 24 countries. Second, the large

east-west divide seen in Table 2 largely disappears when attention is focussed

on behaviour of the well educated. The level of women’s education is similar

and, while fertility, on average, is lower in the east than the west, the

difference is small. Third, the indications for future fertility decline tend

to be positive. Close to one-third of women of reproductive age have received

secondary or higher schooling and their fertility is currently not much above

three births, compared with about five for all women. Secondary school

enrolments are destined to increase in the future and, more importantly, the

less well educated are likely to follow the reproductive path of their better

educated counterparts.

The lessons of success

Two

countries, Ethiopia and Rwanda, have experienced remarkably sharp recent

fertility declines. What can be learnt from these successes?

Ethiopia’s

population is estimated to be about 100 million, the second most populous

country in sub-Saharan Africa. Despite rapid growth in GDP in the past 10

years, it remains one of the world’s poorest countries and is the world’s

largest recipient of international food aid. School enrolments have improved

but adult educational levels are low. Half of women of reproductive age have

received no schooling and, as shown above, the percentage with secondary

schooling is exceptionally low.

Despite

these disadvantages, the country has achieved an impressive degree of

demographic modernisation. For instance, life expectancy improved by close to

16 years between 1990 and 2013, whereas the gain for Africa as a whole was only

about six years. Similarly, fertility fell from seven births per woman in the

early 1990s to 4.6 births in 2010-15, a drop of 35% compared with a drop over

the same period of 18% for the entire region.

Strong

policies and programmes can take much of the credit for these stunning

achievements (Halperin 2014). The 1993 population policy set explicitly

demographic goals of reducing fertility to four births and raising

contraceptive use to 44% by 2015. In 2004, the abortion law was liberalised. A

cadre of over 30,000 mainly female community-based health and family planning

workers was trained for one year and posted back to their own localities. One

lesson from Ethiopia, like that of Bangladesh in the 1980s, is that major

progress towards low mortality and fertility can be made in the absence of

broad socio-economic development given political will and programmatic

efficiency.

Rwanda,

a much smaller and more densely populated country than Ethiopia, is placed at

position 163 out of 188 on the human development index, the same as Uganda but

slightly higher than Ethiopia at position 174. The country adopted a

pronatalist stance in the aftermath of the genocide but in 2003, the policy

changed to the goal of reducing population growth and, as in Ethiopia, a strong

emphasis was given to outreach family planning services. Between 2005 and

2014/5, the percent of married women using a modern contraceptive method rose

from 10 to 48% and fertility fell from six to a little over four births per

woman, an astonishingly rapid transformation.

The

key lesson from Ethiopia and Rwanda appears to be that determined government

initiatives can bring about rapid reproductive change as part of a wider agenda

of health improvements, educational expansion and economic vibrancy. Both

political regimes run relatively efficient administrations that are capable of

mass mobilisation and implementation of effective nationwide programmes. Both

are autocratic, with little tolerance for opposition, and it remains uncertain

whether political evolution towards greater inclusiveness and freedom of

expression will occur. The civil insurrection in Ethiopia in October 2016 is

certainly a warning sign that a more inclusive approach is needed.

Nevertheless, the experience of these two countries is relevant to the more

secure and competent regimes in Africa.

Discussion

As

stated at the outset of this paper the future size of the world’s population

depends largely on what happens to fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. The skilled

and experienced team of demographers at the UN Population Division think that

the pace of decline will continue to be as gentle as in the past. They may well

be correct, particularly for west Africa. Some of the evidence reviewed here,

however, suggests that sharper declines could be achieved. In addition, rapid

urbanisation is expected in Africa. Though this will result in a proliferation

of slum populations, fertility is markedly lower in urban slums than in rural

areas and thus rural-urban migration will favour drops in childbearing. Further

expansion of secondary schooling will also accelerate the pace of change, as

will increased exposure to mass media.

Developments

in the application of birth control technologies are a further relevant factor.

Hitherto, injectable contraception has been dominant. Though highly effective,

this type of method requires re-supply every two or three months.

Discontinuation because of side effects and health concerns is common and

switching to an alternative method is low. The link between contraception and

pregnancy-avoidance is thus weakened. In response, there is a new emphasis on

the promotion of long-acting reversible methods, intra-uterine devices and

implants, which have much lower rates of discontinuation than injectables,

perhaps because stopping requires a conscious decision to remove the device.

Use of implants, but not IUDs, is now rising rapidly in many countries. The

proliferation of medical abortion products, often available illegally across

the counter in medical stores, may already be having an effect on childbearing,

particularly among sexually active single young women for whom the stigma of

abortion is less than the shame and threat to prospects of motherhood

(Johnson-Hanks 2002).

The

most compelling grounds for optimism concerns politics, both international and

domestic. Just as the fertility transition was starting in Africa in the early

1990s, international concerns about high fertility and rapid population growth

waned. At the 1994 Cairo conference on population and development, the agenda

of population control was swept aside and replaced by a broader vision of

women’s reproductive health, rights and empowerment. Subsequently, the

desirability of curbing population growth, and even the word “contraception”

disappeared from international discourse. In Africa, family planning funding

was diverted to a new emergency, HIV. As high fertility and rapid population

growth jeopardises employment prospects, food security, improvement of human

capital and the environment, Africa’s long term prospects were severely damaged

by the new international consensus.

The

pendulum of international opinion has now swung back. The worst of the HIV

pandemic is over, new concerns have arisen about the world’s ability to feed a

growing population without further severe environmental damage, and the huge

surge in Africa’s population has raised alarms about mass migration from

poverty and hunger. In 2012, the London Family Planning Summit pledged to reach

an extra 120 million women with affordable contraception by 2020. Funding has

increased and the reluctance to talk openly about the subject has abated.

This

change at the international level will achieve little without changes at

national governmental level. Here also, positive developments are apparent. The

concept of a “demographic dividend” has traction among African politicians and

economists. This dividend, or boost to living standards, arises when the

falling fertility brings in its wake a rise in the ratio of adult workers to

dependent infants and children. Econometric evidence suggest that this change

in age structure made a large contribution to rapid improvements in income per

head in east Asia. This prospect is appealing to African elites. Poverty

reduction is a universal goal and the narrative of the demographic dividend

neatly circumvents explicit mention of curbing population growth, though, of

course, it will have exactly this effect. President Museveni of Uganda,

historically an opponent of family planning promotion, has been convinced and

other leaders are showing similar signs, spurred on by endorsements from the

World Bank and IMF (May 2016). We are entering an era when political will and

(hopefully) international funding may act in concert to accelerate reproductive

change. The re-imposition by President Trump in January 2017 of the global GAG

rule that prevents US funding of any non-government organisation that in any way

promotes or facilitates access to abortion is a backward step but in the past

this restriction has not made a decisive difference to overall funding for

family planning, in part because other donors made good the deficit.

References

Bongaarts,

J. 2016. Africa’s unique fertility transition. Population and Development Review DOI:10.1111/J.1728-4457.2016.00164.X

Caldwell,

JC and Caldwell P. 1987. The cultural context of high fertility in sub-Saharan

Africa. Population and Development Review 13(3):409-437

Caldwell

JC, Orubuloye IO, and Caldwell P. 1992. Fertility decline in Africa: A new type

of transition? Population and Development

Review 18(2):211-242

Gerland

P, Biddlecom A and Kantorova V 2016. Patterns of fertility decline and the impact

of alternative scenarios of future fertility change in sub-Saharan Africa.

Population and Development Review DOI:10.1111/padr.12011

Halperin

D. 2014. Scaling up of family planning in low-income countries: lessons from

Ethiopia. Lancet 383:1264-67

Johnson-Hanks

J. 2002. The lesser shame: abortion among educated women in southern Cameroon. Social Science and Medicine 1337-1349

Lightbourne

RE 1987. Reproductive preferences and behaviour. In Cleland J and C Scott (eds) The World Fertility Survey: An Assessment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

pp.838-861.

Machiyama

K et al. 2015. An assessment of childbearing preferences in Northern Malawi. Studies in Family Planning 46(2):161-176

May

J. 2016. The politics of family planning policies and programs in sub-Saharan

Africa. Population and Development

Review DOI:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2016.00166.x

Moultrie

T, Sayi T and Timaeus I 2012. Birth intervals, postponement and fertility

decline in Africa: A new type of transition. Population Studies66(3):241-258

Potts

M, Henderson C, Campbell M. 2013. The Sahel: A Malthusian challenge. Environmental Resource Economics 55:501-512.