Limits to growth: Human economy and planetary

boundaries

Kerryn

Higgs

Kerryn

Higgs is an Australian researcher and author who published Collision Course: Endless

growth on a finite planet (MIT

Press) in 2014. She completed her PhD with the School of Geography and

Environmental Studies at the University of Tasmania, where she is now a

University Associate in the School of Social Sciences. She is also an Associate

Member of the Club of Rome.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

DOI: 10.3197/jps.2017.2.1.15

Licensing: This article is Open Access (CC BY 4.0).

How to Cite:

Higgs, K. 2016. 'Limits to growth: Human economy and planetary boundaries'. The Journal of Population and Sustainability 2(1): 15–36.

https://doi.org/10.3197/jps.2017.2.1.15

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Abstract

The idea of physical limits to

human economic systems is advanced by physical scientists and ecological

economists, as well as appealing to the common sense proposition that unending

growth in physical processes such as material extraction and waste disposal

will ultimately be inconsistent with any finite entity, even one as large as

the Earth. Yet growth remains the central aim of business and government almost

everywhere. This paper examines the history of the idea of economic growth and

the many influences and interests that supported — and still support — its

enshrinement as the principal aim of human societies. These include the

apparatus of propaganda in favour of corporate interests; the emphasis on

international trade; the funding of environmental denial; and, underlying all

these, the corporate requirement for profit to continue to increase. The

dominance of these influences has serious consequences for the natural world

and growth has failed to solve the problems of poverty.

Keywords: Limits to Growth; propaganda;

consumerism; environmental denial; planetary boundaries.

The

authors of The Limits to Growth (Meadows

et al., 1972) were not the first to draw attention to physical limits on the

expansion of the human economic system, but they enjoyed substantial attention,

especially in 1970s, and brought the concept into mainstream thinking. The

project came out of the concerns of the founding members of the Club of Rome

and drew on the discipline of systems analysis being developed at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

The

Club of Rome, founded by Italian industrialist Aurelio Peccei and Scottish scientist

Alexander King, brought together a select group of prominent, mostly wealthy

individuals who wanted to address what they called the problematique,

translated as “the predicament of mankind”. Peccei saw post-war economic and

industrial advance as a double-edged sword and described himself as “perplexed

and worried by the orderless torrential character of this precipitous human

progress” (Barney, 1982, p.607). Soon after it was founded in 1968, the Club

commissioned the Limits to Growth project at MIT with researchers Donella

Meadows, Dennis Meadows, Jørgen Randers and William Behrens.

The

MIT team identified five major aspects of this predicament: accelerating

industrialisation, rapid population growth, extensive malnutrition, depletion

of non-renewable resources, and environmental decline. They formulated this

question: how could growing populations, locked into ever-expanding

industrialisation, avoid immense environmental degradation, exhaustion of the

resources on which everything depends, and the social chaos that would be

likely to follow decline or collapse? To answer this question, they devised

World3, a computer program that combined extensive data about the many

interacting aspects of the economy and the environment, with different scenarios

about changes that might be made. These scenarios ranged from business as usual

(the standard run), through several combinations that assumed extremely

advanced technology, to scenarios where both population and physical throughput

were stabilised. The standard run led to collapse around the middle of the

current century. Even massive technological advance could not avert this

outcome, but there were scenarios that could: those that stabilised population

and wound back the scale and rate of material extraction and waste.

The

book remains the best-selling environmental book ever published, but its

reception in the political and economic mainstream was mixed. In the early

years, both US President Carter and Prime Minister Trudeau of Canada took it

seriously and launched parallel studies (Barney et al., 1981; Barney, 1982;

Voyer and Murphy, 1984). From the beginning, however, most economists ridiculed

the idea that human economic systems have physical limits (Beckerman, 1972;

Economist, 1972; Nordhaus, 1973; Solow, 1973), an attitude which came to

prevail. One characterised the World3 computer program as “Garbage in, garbage

out”. Robert Gillette (1972), who reported for Science at the launch of the book, noted that

the “assumption of inevitable economic growth” constitutes “the very

foundation” of the economics profession—which may help to explain the intensity

of the assault from economists.

In

recent years, several researchers (Hall and Day, 2009; Turner, 2014) have

compared the Meadows projections with what has actually happened. The

correlation between the standard run (business as usual) and real world trends

over the intervening years is extremely close. Hall and Day (2009) could not

find “any model made by economists that is accurate over such a long time span”.

Given that the projections up to 2010 have proven accurate, it would seem wise

to question the pursuit of business as usual.

Unprecedented Growth since

1950

Growth,

of both economies and populations, was indeed “torrential” in the years after

the end of World War II, especially the first three decades. The world’s

population increased from just over 2.5 billion in 1950 to almost 4 billion in

1975.[1] In the same period, world GDP more than

doubled. Thus, by 1975, the base of both the economic system and human numbers

was already immense and doubling times were short. By the 1990s, annual

increase in world GDP has been estimated to approximate the entire global

output of 1900, about one trillion in 1990 US dollars (DeLong, 1998).[2]Although

economists like to argue that humans have been exploiting their resources and

pursuing economic growth since the Stone Age (Solow, 1974; Beckerman, 1972),

there has never been anything like the twentieth century.

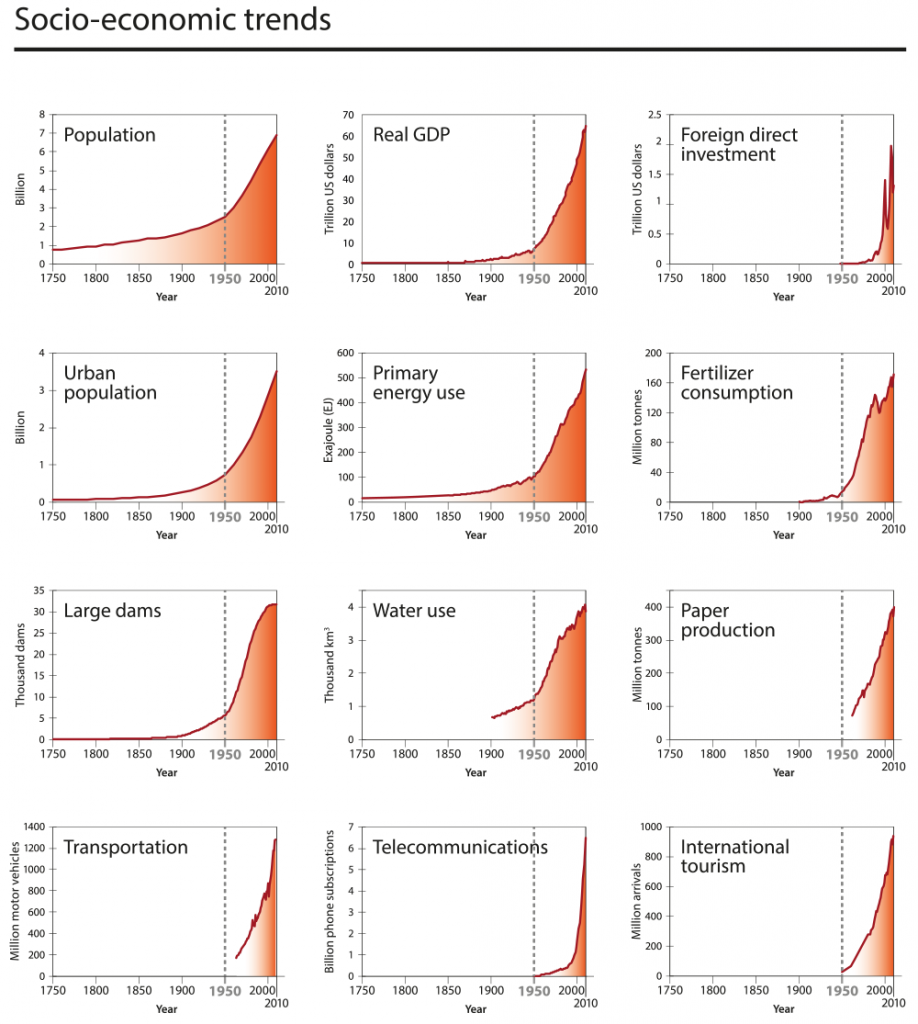

Australian

climate scientist Will Steffen and colleagues have shown just how unusual it

was, in the sets of exponential graphs known as “The Great Acceleration”

(Steffen, Broadgate, et al., 2015). The graphs start at the year 1750 and run

to 2010; the disjunction around 1950 is clear in all of them. Figure 1 shows

the economic aspects of the growth boom. Despite the financial crisis of

2007-2008, the continuation of this trajectory is sought, to the maximum extent

possible, by governments and international organisations.

Figure 1. The Great

Acceleration, social and economic aspects, courtesy Will Steffen.

The

economists’ intense attack on Limits

to Growth reflects

the rift between the core assumptions of mainstream economics and those of the

physical sciences. Basic economics textbooks depict a standard model where the

circular flow between production and consumption has no natural context:

producers and consumers are seen to function without any reference to the

physical world of resources and wastes. Ecological economists, on the other

hand, and most physical scientists, accept Nature as the essential foundation

of the human economy; in this framework, production requires resource inputs from the

physical world and sinks where its wastes can be absorbed: depletion and

pollution are inescapable.

In

mainstream economics, economic growth is understood to be the result of two

factors: capital and labour. This picture was developed while energy and

resources were plentiful; economists could ignore the physical basis of

economic activity, including the role of energy. Physical scientists, on the

other hand, regard energy as the “master resource”, since no other commodity

can be produced without it (Cleveland, 1991; Zencey, 2013).[3]One

of the ecological economists, Kenneth Boulding, warned in 1966 that the

“cowboy” economy (which had commanded the limitless resources of an “empty

world”) was over; humanity faced a new situation which he called “spaceship

Earth”, a world that was rapidly filling up. Odd as it may seem, economics has

yet to fully acknowledge that energy is just as essential to production as are

labour and capital, even though the massive economic growth since 1950 has

depended on it.

Economic growth as a corporate

goal: inventing consumerism

Notions

of limits to economic growth threaten many powerful groups that depend on

continually rising profits and the expansion of the physical economy. One of

the crucial innovations of capitalism[4] was the system of accumulation, where

production surpluses are largely devoted to expansion of the enterprise. Growth

is indispensable to such a system, and the corporations that emerged around

1900 were determined to maintain it. The immense productive powers developed

over the nineteenth century had met the basic needs of most of the US

population by the early twentieth century and the captains of industry feared

that the system had triggered a permanent crisis of overproduction. The American

capitalist economy confronted the plenty it had created as a threat to its very

existence.

A

consumer solution, however, was simultaneously emerging. Edward Bernays[5]

(2005), one of the pioneers of the public

relations industry, pointed out in 1928 that mass production can only be

profitable if it ensures steady or increasing demand, which, he suggested,

could be accomplished “through advertising and propaganda”. Although the

practice of inciting consumption has earlier roots (Higgs, 2014, pp.68-69), the

first major surge of mass consumption was promoted in America in the 1920s. A

“new economic gospel of consumption” was urged (Cowdrick, 1927); new needs

could be created, with advertising enlisted to “augment and accelerate” the

process (Hunnicutt, 1996). People could be encouraged to give up thrift, value

goods over free time and, with ever-increasing aspirations, they would always be

chasing a receding goal. Just before the Wall Street Crash, President Herbert

Hoover’s Committee on Recent Economic Changes (1929) welcomed the “grand…

expansibility of human wants and desires”, celebrated an “almost insatiable

appetite for goods and services”, and foresaw “new wants that make way

endlessly for newer wants, as fast as they are satisfied”. People were

encouraged to board an escalator of desire (a stairway to heaven, perhaps) and

progressively ascend towards the luxuries of the affluent.

Although

the Great Depression interrupted this process, it resumed after World War II

with an intensity stimulated by corporate advertisers using debt facilities and

the new medium of television. As retail analyst, Victor Lebow, put it in 1955:

Our

enormously productive economy demands that we make consumption our way of life…

that we seek our spiritual satisfaction, our ego satisfaction, in consumption.

… We need things consumed, burned up, replaced and discarded at an ever

accelerating rate (Kettles, 2008, p.47).

Vance

Packard (1959) described the advertising men of this new era, putting “sizzle

into their messages by stirring up our status consciousness”, making what were

once luxuries into the “necessities of all classes”. Sold as status symbols

perhaps, it was endless material objects that were being consumed.

The

prospect of ever-extendable consumer desire, characterised as “progress”,

promised a new way forward for modern manufacture, a means to perpetuate

economic growth. Progress required the endless replacement of old needs with

new, old products with new. Notions of meeting everyone’s needs with an

adequate level of production did not feature. In this sense, the twentieth

century capitalist era unleashed desire with its complex individual peculiarities

and set it loose in the marketplace of material goods, supplanting basic

survival needs as the purpose and driver of economic growth. Up to now, there

has been little change in this strategy. As we run up against the limits of

material production, nothing could be more inimical to finding solutions.

Economic growth as policy goal:

the idea takes over

In

the reports of the IMF, World Bank, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD) and G20, and in the speeches of our politicians, economic

growth is seen as imperative, and it may seem that government—and

international—economic policy has always embraced this view. However,

Australian economist H W Arndt (1978) demonstrated that the idea of economic

growth as a policy objective appeared quite abruptly in the 1950s—as did the

idea of “development”. Governments pursued neither material development nor

economic growth during the first half of the twentieth century, academic

economists rarely discussed it, and neither businessmen nor politicians thought

governments had any role in promoting it (Arndt, 1978).

At

his inauguration in 1949, President Harry Truman signalled a departure from

this position[6],

announcing the intention of the US to extend modern industrial production to

every corner of the earth: “More than half the people of the world are living

in conditions approaching misery…. Greater production is the key to prosperity

and peace…. [and will require] a wider and more vigorous application of modern

scientific and technical knowledge” (Truman 1949).

Soon

afterwards, a new field of economics emerged, defining the well-being of the

world’s people in terms of economic growth and the exploitation of resources.

The new “development economists” echoed Truman’s vision of technology as the

engine of human progress, and stressed capital accumulation as the central

facilitator. Energy did not play any role in their theories. Walt Rostow (1960)

held that “the age of high mass-consumption” is the ultimate stage of progress.

W Arthur Lewis (1954) argued that traditional cultures and subsistence

livelihoods must be swept away and replaced by the industrial money economy, a

necessary and inevitable process.

“We

are interested”, Lewis wrote, “not in the people in general, but only in the 10

per cent of them with the largest incomes…. The central fact of economic

development is that the distribution of incomes is altered in favour of the saving

class”. In this respect, the development economists adopted a “trickle down”

approach to solving the misery Truman lamented. Lewis focussed on consolidating

the wealth of the rich, who would instigate an economic “take-off”; at a later

stage, he believed, the resulting economic growth would reach the poor. In

recent times, neoliberal ideology embraced the same idea, with its claim that

cutting taxes for the wealthy leads them to invest and therefore benefit

everyone. Neither the expectations of the development economists nor the claims

of the neoliberals are supported by empirical evidence. In both cases, wealth

has “trickled up” (Higgs, 2014, pp.119-123).

Quest for the bigger pie

Several

imperatives underpinned the new scramble for economic growth in the post-war

world. After the Great Depression, full employment was regarded as an essential

policy objective and economic expansion was believed to be the only practical

way to achieve such a goal. In the “developing” world too, where national

liberation movements had to be accommodated or neutralised, growth was

preferred to redistribution of land or resources. Although growth has increased

the numbers of the middle class in some developing countries, especially China,

and despite persistent claims that economic growth has “lifted millions out of

poverty”, the reality is not so rosy. More than half the world’s people still

live in poverty, without reliable material security, even if the definitions

used by the rich world’s institutions tend to obscure the fact. Prosperity is

concentrated among a privileged minority (Higgs, 2014, pp.105-162; Hickel,

2017).

The

so-called “bigger pie” was promoted as the obvious solution to all social

problems—debt, unemployment, poverty, and even the environmental damage involved

in baking it. It still remains the primary strategy for the institutions of the

OECD world, whether businesses, national governments, or the international

bodies allied to business. In these forums, no-one asks where we are to find

the ever less accessible ingredients for this ever more gargantuan pie.

Post-war

theories of economic growth harboured two key assumptions—and continue to do

so. Firstly, economic growth is regarded as an inevitable stage of human

civilisation, a natural and linear progression from more “primitive” social

forms. Secondly, economic growth is seen as a process of indefinite duration,

with no limits in space or time. On a graph, it is a curve which continues

upward forever, permanently exponential. Such beliefs are a form of magical

thinking. They ignore problems of resource scarcity, especially that of energy,

they ignore waste and they ignore the destruction of the natural world in which

everything is based.

Arndt’s

fears that the limits critique would end the pursuit of economic growth were

groundless; in fact, the influence of such ideas waned as neoliberalism

increasingly monopolised the economic discourse, and began to dominate

government policy from around 1980 when Ronald Reagan was elected as US

President, and Margaret Thatcher had just settled into Downing Street.

Naturalising the “free market”

Neither

natural nor inevitable, the so-called free market has received massive advocacy

for more than a century—in order to create, retain and extend public

acceptance. The roots of this process lie back in the early decades of the

twentieth century, just as the modern corporation was emerging (Higgs, 2014,

pp.167-169). By the 1920s, with Edward Bernays in the lead, public relations

(PR) began to gain ground as a career path. As Bernays (2005, pp.37-38)

explained in 1928, with a candour rarely heard these days:

The

conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organised habits and opinions of

the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate

this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is

the true ruling power of our country. … It is they who pull the wires which

control the public mind.

Bernays

described himself as a “propaganda specialist” or a “public relations counsel”.

He and his colleagues were anxious to offer their services to corporations and were

instrumental in founding an entire industry that has since operated along these

lines, selling not only commodities but also opinions on a great range of

social, political, economic, and environmental issues.

One

early PR man, Ivy Lee, simply made up facts to suit the purpose (Higgs, 2014,

p.170), a precursor of the “alternative facts” which have become more palpable

than ever since 2016. Later, with the advent of Bernays, PR centred on the

careful construction of image: for example the idea that corporations exist to

serve, rather than turn a profit; the displacement of the term “big business”

with a new enemy, Big Government; the denigration of public servants and

politicians as “fat cats” while CEOs were depicted as models of generosity; and

the replacement of terms like capitalism, laissez faire and private enterprise

with the sanitised expression “free enterprise” (Higgs, 2014, pp.175-178).

The

work of hired propaganda specialists was augmented by that of think tanks later

in the twentieth century. Just a handful of these institutions predate 1970;

but by 2015, their number was estimated at almost 7,000 (McGann, 2017). Funded

by corporations that prefer to avoid regulation (for example tobacco, asbestos,

chemicals, fossil fuels, mining, car manufacturers), business-friendly

activists set out to “litter the world” with “free enterprise” think tanks

(Cockett, 1995, p.307). In the US, the family foundations where fortunes of

corporate leaders are often held also chipped in handsomely (Higgs, 2014, p.90,

pp.191-192).

These

ferociously proliferating think tanks have disseminated industry propaganda as

“independent research” ever since. Most are tax-exempt and vociferous claims to

independence disguise their political ties. One think tank operative, however,

told researcher Georgina Murray (2006) that it would be naive to imagine that

think tanks are established “by Santa Claus or the tooth fairy”. Rather, as

Irving Kristol (1977) admitted, they are always intended to “shape or reshape

the climate of public opinion”. Think tank staff enjoy immense influence in the

media of the English-speaking world, where they are depicted as scholars on a

equal footing with peer-reviewed academics and have also been recruited into governments.

Heritage, American Enterprise Institute and Hoover supplied 150 of Reagan’s

staff—and numerous Heritage operatives were “borrowed” by George W Bush. In the

UK, the Thatcher government owed much to the Institute of Economic Affairs and

the Centre for Policy Studies (Higgs 2014, pp.96-98, 214-215).

Think

tanks promoted the bogus standard of “balance” in place of impartiality and

accuracy, as they pursued “equal time” in media and educational institutions.

Analysis of the US prestige press between 1988 and 2002, showed that “balanced”

reporting successfully obscured the scientific consensus on global warming by

giving equal, or even greater, space to those who denied that climate change

was occurring (Boykoff and Boykoff, 2004). This trend is symptomatic of

multiple efforts to undermine any science that threatens polluting industries

(Higgs, 2014, pp.211-238) and demonstrates the efficacy of “balance” as a tool

of obfuscation.

The drive for “free trade”

By

the early 1980s, neoliberal ideology was established as the economic creed of

the governments of the UK, US and Australia and had begun to penetrate

international institutions. When assisting developing countries, the IMF now

insisted on Structural Adjustment Programs which required strict market policies

in exchange for its help. These programs were rarely in the interests of the

citizens of these countries: privatisation, deregulation, balanced budgets,

abolition of welfare measures and removing barriers to foreign investment

usually disadvantaged the poor.

By

1986, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), founded in 1948, had

attracted 108 member countries and slashed tariffs by 75 per cent. Like “free

enterprise”, free trade is not so much about freedom, but about abolishing

rules for corporations and substituting rules for governments and citizens.

Already, under the GATT arrangements, rules relating to environment, health or

working conditions were excluded as not “trade-related”. The World Trade

Organisation, fiercely pursued by corporate lobbyists, was finally established

in 1995, and followed the same blueprint. Dispute panels of both entities were

run by corporate lawyers or economists with no input from environmental

experts.

Under

the trade regime of the GATT-WTO system, trade has priority over environmental,

health, and social justice considerations, regardless of the wishes of a

government and the people it represents. To enforce trade obligations, the

rules penalise countries if they choose to assess risk and protect citizens or

environment under their own standards. For example, it is regarded as

irrelevant if fish are caught with collateral slaughter of dolphins, or if

residues of pesticide or growth promoting hormones exceed local limits. The

burden of proof is reversed, so that citizens must prove commodities are unsafe

rather than manufacturers having to show they are safe.

Although

the GATT concentrated on removing tariffs on actual goods, the WTO and

subsequent multi-party agreements such as the North American Free Trade

Agreement, moved to abolish restrictions on capital flows, making it nearly

impossible to prevent stampedes of capital in and out of countries on

speculative errands. Overall, economic goals gained precedence over all other

priorities. By the new century, business priorities were entrenched in public

discourse, government policy, and international institutions (Higgs, 2014,

pp.246-254). Economic growth was established almost everywhere as the only way

to solve any problem. Environmental protection and social justice, both

national and worldwide, were now deemed to depend on it.

Approaching the planetary

boundaries: four major problems

Over

the twentieth century, physical production increased twenty-fold and human

population quadrupled. The consequences continue to cascade through the natural

and human world, literally liquidating life on earth. Although the roots of

this post-war growth lie deep in our history, it was not until about 1950 that

the scale of the human project began to outgrow planet Earth decisively. It

might not have mattered so very greatly at other points in history, but frantic

attempts to restart the growth curve of the past 70 years and to enshrine

economic growth as the central element in government policy are now in conflict

with physical reality.

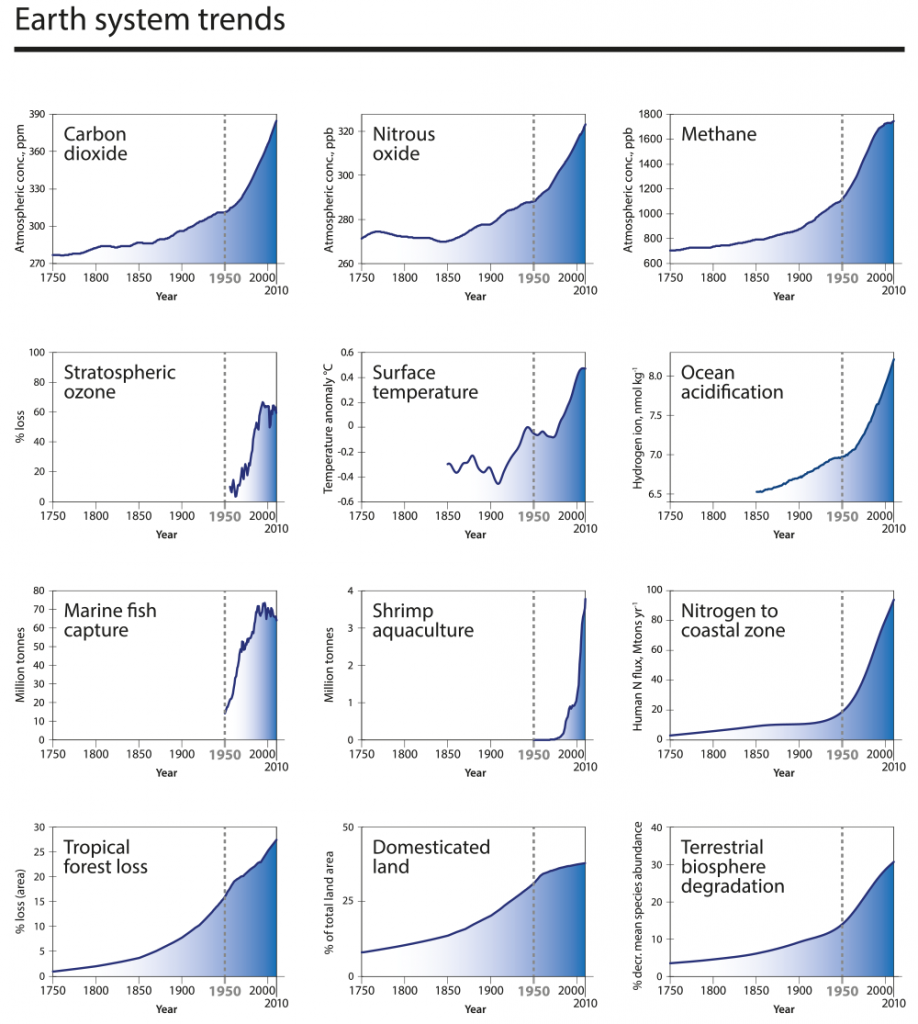

Figure

1 showed the economic aspects of the growth boom. Figure 2 shows the

corresponding

physical changes in the natural world. From the 1960s onwards, scientists such

as Rachel Carson sounded alarm about various problems associated with growth,

but this was not the case in governments, bureaucracies and public debate,

where economic growth was gradually being entrenched as the central objective

of collective human effort. The transition to service economies in developed

countries has not moderated the global trajectory of either economic or natural

impacts, since our consumption continues to increase, with even greater

quantities of far cheaper material objects imported from the countries that now

conduct manufacture.

Figure

2. The Great Acceleration, impacts on Nature, courtesy Will Steffen.

Figure

2. The Great Acceleration, impacts on Nature, courtesy Will Steffen.

The

concept of planetary boundaries has been developed by a team led by Johan

Rockström of the Stockholm Resilience Centre and Will Steffen from the

Australian National University. It is a work in progress and the exact extent

to which we are breaching these boundaries is still being quantified; the

team’s most recent paper (Steffen, Richardson, et al., 2015) argued that two

problems are already extremely dangerous and two others are well on the way.

Biodiversity

The

boundaries team argues that the most serious problem is loss of biodiversity.[7]

We are losing species 100 to 1,000 times

faster than the background rate through geological time and the world lost

something like 50 per cent of all its mammals, birds, fish, amphibians and

reptiles in the forty years following 1970. This research refers to numbers of

animals, not species, but smaller populations are increasingly vulnerable

(Ceballos et al., 2015; WWF, 2014).

Trade

plays a crucial role in obscuring the location of the ecological damage

embodied in consumer products. It allows the people who consume most of the

goods to transfer the damage involved to the generally much poorer people who

host the extraction of the materials they are made from and the factories where

they are made. Manfred Lenzen and his team (2012) estimated that some 30 per

cent of extinctions are related to trade. The website shipmap.org gives a

graphic picture of the immense scale of trade by sea; trade by air is also

extensive. My own country, Australia, occupies an unusual position for a

developed country. Mainly through agriculture—and to some extent mining—we

sustain more ecological damage on behalf of others than we export through

consuming products made elsewhere. Consumption in the US, Japan and Europe,

however, transfers significant ecological damage, especially to countries in

Africa and South-East Asia.

Disruption of biogeochemical

cycles

For

Steffen and colleagues the second most immediate danger lies in the impact of

fertilisers: the nitrogen and phosphorous cycles are radically disrupted. In

Nature, most nitrogen was inert in our atmosphere (though mobilised by bacteria

and leguminous plants). Mainly through making fertiliser, nitrogen is now

flooding through our rivers, groundwater and continental shelves, causing algal

blooms and dead zones where fish, molluscs and aquatic insects may die,

sometimes in large numbers.[8]

In the case of the other widely dispersed

fertiliser, phosphorous, there is an added danger—phosphate rock is a resource

in decline, with grim implications for agriculture (Cordell, 2017). Phosphorous

is an element, one of the indispensable building blocks of DNA, and no market

on earth will be able to manifest a substitute, though it could be recovered

from human waste.

Land use changes

Land

use change is in the “amber zone”, close to crossing the boundary into extreme

danger; it is also implicated in the threat to biodiversity. Humans are still

clearing millions of hectares of vegetation every year and draining wetlands.

Tropical forests of Asia and Africa are being replaced by palm oil plantations,

also expanding in Latin America, where clearing already provides cattle

pasture, soybean and sugar cane. Oil palm plantations involve the death of

immense numbers of individual animals and the annihilation of vast tracts of

tropical forest. In China and South Korea, wetlands that support migrating

birds are being drained and transformed into ports. Growing populations, in

both rich and poor countries, contribute to this pressure (Crist, Mora and

Engelman, 2017).

Global warming

Also

in the amber zone is global warming. We are well on the way to a very hot

planet and, to remain below the 2°C target, we require technologies which do

not yet exist for extracting carbon from the atmosphere. Even if the

commitments made in Paris are all honoured, it will already be 2°C hotter than

pre-industrial times[9]

by 2050 and at least 2.7°C hotter by

2100. The aspirational 1.5°C target is likely to be reached by the early 2030s

(Watson et al., 2016).

This

situation is better than the likelihood of 4°C which applied before Paris, but

there is no guarantee that we will limit the damage to 2.7°C. Even if we do,

that temperature will reduce crop yields, make many places unliveable, melt the

glaciers that supply water to billions in Asia and South America, destroy coral

reefs and many other species, and produce significant—even catastrophic—sea

level rise. James Hansen and his team (2015) regard 2°C as already posing a

dangerous sea level threat, as much as 3m this century. The Greenland icesheet

is melting at an accelerating rate. Not considered likely a decade ago, the

entire coast of West Antarctica is dotted with ice shelves that are shrinking

or collapsing as warm seawater intrudes underneath. Glaciers are speeding up as

a result; Pine Island glacier is considered to be melting irreversibly, as is

Thwaites and other adjacent glaciers (Rignot et al., 2014). It is expected to

take several centuries before really catastrophic sea level rise occurs, but

Hansen et al. (2016), as well as many glaciologists, warn that the melting of

the polar icesheets involves non-linear processes of disintegration, so the

timing is unknown and may be far quicker than assumed.

Pollution

Alongside

these four major crises (species loss; disruption of the biogeochemical cycles;

land clearing; and global warming), Steffen’s team is also aiming to quantify

how close we are to being overwhelmed by pollution and novel substances. This

aspect of their project is ongoing, but we do know that there are more than 5

trillion plastic fragments in the ocean, so prevalent that 90 per cent of sea

birds are now ingesting them, while deep sea creatures are eating micro-plastic

fibres disgorged by our washing machines (Eriksen et al., 2015; Taylor et al.,

2016). And we do know that the ocean is acidifying.

Conclusion

As

the historian Dipesh Chakrabarty (2009) noted, what is new about the pursuit of

the study of history in the twenty-first century is the need to address the

intersection between natural history and human history. The key to this

collision is the concept of scale, an insight brought to prominence by the

ecological economists. Herman Daly and his colleagues perceived that the scale

of the human project in relation to the scale of the planet had reached an

unsustainable ratio. Especially since World War II, the human project has

altered—and continues to alter—the actual physical condition of the earth.

While

deniers of ecological crisis like to argue that notions of human impacts on the

geophysical scale are laughable, this attitude reveals an ignorance of natural

history. It is scientifically uncontested that humble cyanobacteria

microscopically producing oxygen over two or three eons created an oxygen-rich

atmosphere suitable for complex life, including ours. If algae can have

planetary impacts—expressed very slowly, but unquestionably a geophysical

force—big animals such as humans are obviously in a position to change the

planet rather faster.

Herman

Daly’s ten-point program (2008) is an excellent example of the sweeping changes

ecological economists consider necessary, most of them totally unacceptable to

corporate capitalism. His policy summary includes ecological tax reform;

limitations on unequal income distribution; the re-regulation of international

commerce; the downgrading of the IMF, World Bank, and WTO; the abolition of

fractional reserve banking; stabilisation of the population; and the transfer

of the remaining commons to public trust. Under the current economic system,

there seems little to no chance that any of these measures would be adopted by

governments that exist at the pleasure of market forces.

And

yet, structural change is indispensable. Some propose a transition to

socialism, others hope to tame the capitalist economy and establish a steady

state economy. Both options seem equally hard to imagine in the neoliberal era.

However, to hijack Margaret Thatcher’s famous expression, “there is no alternative”.

We

need a different kind of economy, one designed to meet needs rather than create

them; we need to abandon the consumer path to human advancement and the

reduction of our choices to monetary terms. The consumer template for the human

future has outworn its usefulness. Stimulating consumption in the interests of

growth and chasing economies of scale was, perhaps, suitable for the “empty

world”. In the “full world” (and getting fuller) we need redistributive justice

within and between countries and a plan for the rich world to reduce its

material demands to allow space for the rest of the world to reach material

security.

[1]. It

is estimated to have exceeded 7.5 billion during 2016.

[2].

DeLong uses several methods. Estimated annual additions for the 1990s vary from

half the entire economy of 1900 to the entire 1900 economy.

[3]. By

the 1950s, empirical studies had shown that capital and labour could explain

only one seventh of observed economic growth in the US. There was no clear

candidate for the rather large missing ingredient, although “technical

progress” was often assumed to provide the best explanation (Ayres and Ayres,

2009, p.11). Later, Robert Ayres (a physicist) and Benjamin Warr identified the

missing factor as energy—or, more exactly, as the increasing efficiency with

which energy and raw materials are converted into useful work. In this

explanation, technological improvement plays a part, but Ayres and Ayres (2009,

pp.9-18) stress that: “labour and capital extract energy;

they don’t make it”. Thus energy is a prerequisite for,

not a product of economic activity.

[4].

With the partial exception of Cuba, socialist and communist economies have been

just as dedicated to industrialisation and economic growth as their capitalist

rivals. Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union were even more severely

polluted than the West, as is China today; although a state-controlled economy,

China is hardly “socialist” (Higgs, 2014, pp.5-7, 11-13).

[5].

Nephew of Sigmund Freud.

[6]. See

Hickel (2017, pp.7-9) for an account of how this came to be included in the

inaugural address.

[7].

Most serious in the sense of most well advanced. Many scientists argue that

non-human species and ecosystems have intrinsic value, a view I share; but even

if one rejects this view, humans nonetheless depend on the fabric of life on

earth for survival—for food, clean water, pollination and numerous other

ecosystem services as well as for novel substances, including drugs (see Crist,

Mora and Engelman, 2017).

[8].

Humans now produce more reactive nitrogen than natural processes do. Excess

nitrogen involves hazards in addition to eutrophication: the greenhouse gas

nitrous oxide (N2O) is released during fertiliser application;

nitrate may also leach into groundwater and contaminate drinking supplies.

[9].

Usually defined as pre-1870.

References

Arndt,

H. W., 1978. The

rise and fall of economic growth. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire.

Ayres,

R. and Ayres, E., 2009. Crossing

the energy divide. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Barney,

G., Freeman, P. and Ulinsky, C. eds. 1981. Global

2000: implications for Canada. Toronto: Pergamon.

Barney,

G. ed., 1982. The

Global 2000 Report to the President: entering the twenty-First century, Volumes

1–3. Harmondsworth,

UK: Pelican.

Beckerman,

W., 1972. Economists, scientists, and environmental catastrophe. Oxford Economic Papers, 24, pp.327–344.

Bernays,

E., 2005 [1928]. Propaganda.

Brooklyn, NY: IG Publishing.

Boulding,

K.E., 1966. The economics of the coming spaceship earth. In: H. Daly and K.

Townsend, eds. 1993. Valuing

the Earth: Economics, Ecology, Ethics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

pp.297-309.

Boykoff,

M. and Boykoff, J., 2004. Balance as bias: global warming and the US prestige

press. Global Environmental Change,

14, pp.125–136

Ceballos,

G., Ehrlich, P., Barnosky, A., García, A., Pringle, R. and Palmer, T., 2015.

Accelerated modern human–induced species losses: entering the sixth mass

extinction. Science Advances, 1, e1400253.

Chakrabarty,

D., 2009. The climate of history: four theses. Critical Inquiry,

35 (Winter), pp.197–222.

Cleveland,

C., 1991. Natural resource scarcity and economic growth revisited: economic and

biophysical perspectives. In: R. Costanza, ed. 1991. Ecological economics: the

science and management of sustainability. New York: Columbia University Press.

pp.289–317.

Cockett,

R., 1995. Thinking the unthinkable:

think-tanks and the economic counter-revolution, 1931–1983. London:

Fontana.

Committee

on Recent Economic Changes, 1929. Report

of the Committee on Recent Economic Changes. [pdf] New York:

McGraw-Hill. Available at: <http://www.nber.org/chapters/c4950.pdf>

[Accessed 13 August 2017].

Cordell,

D. and White, S., 2014. Life’s bottleneck: sustaining the world’s phosphorus

for a food secure future. Annual

Review of Environment and Resources, 39, pp.161-188.

Cowdrick,

E., 1927. The new economic gospel of consumption. Industrial Management,

74, pp.209–211.

Crist,

E., Mora, C. and Engelman, R., 2017. ‘The interaction of human population, food

production, and biodiversity protection’. Science,

356(6335), pp.260–264.

Daly,

H., 2008. A steady-state economy. London: Sustainable Development Commission,

UK. Available at: <http://www.theoildrum.com/node/3941> [Accessed 11 Aug.

2017].

DeLong,

J., 1998. Estimating world GDP, one million B.C. – present. Department of

Economics, UC Berkeley, [online] Available at:

<http://www.j-bradford-delong.net/TCEH/1998_Draft/World_GDP/Estimating_World_GDP.html>

[Accessed 15 May 2017].

Economist,

1972. Limits to misconception, March 11, pp.21–22. The Economist.

Eriksen,

M., Lebreton, L., Carson, H., Thiel, M., Moore, C., Borerro, J., Galgani, F.,

Ryan, P. and Reisser, J., 2014. Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans: more

than 5 trillion plastic pieces weighing over 250,000 tons afloat at sea. PloS ONE, 9, e111913.

Gillette,

R., 1972. The limits to growth: hard sell for a computer view of doomsday. Science, 175, pp.1088–1092.

Hall,

C. and Day, J., 2009. Revisiting the limits to growth after peak oil. American Scientist, 97, pp.230-237.

Hansen,

J., Sato, M., Hearty, P., Ruedy, R., Kelley, M., Masson-Delmotte, V., Russell,

G., Tselioudis, G., Cao, J., Rignot, E., Velicogna, I., Kandiano, E., von

Schuckmann, K., Kharecha, P., Legrande, A., Bauer, M. and Lo, K-W., 2015. Ice

melt, sea level rise and superstorms: evidence from paleoclimate data, climate

modeling, and modern observations that 2 °C global warming could be dangerous. Atmospheric Chemistry and

Physics, 16, pp.3761-3812.

Hansen,

J., Sato, M., Kharecha, P., von Schuckmann, K., Beerling, D., Cao, J., Marcott,

S., Masson-Delmotte, V., Prather, M., Rohling, E., Shakun J. and Smith, P.,

2016. Young People’s Burden: Requirement of Negative CO2 Emissions. [pdf] Earth Syst. Dynam. Discuss.,

in review. Available at:

<http://www.earth-syst-dynam-discuss.net/esd-2016-42/esd-2016-42.pdf>

Accessed 13 Aug. 2017.

Hickel,

J., 2017. The Divide: a brief guide to

global inequality and its solutions. London:

Penguin.

Higgs,

K., 2014. Collision Course: endless

growth on a finite planet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hunnicutt,

B., 1988. Work without end: abandoning

shorter hours for the right to work. Philadelphia, PA: Temple

University Press.

Kettles,

N., 2008. Designing for destruction. Ecologist,

38(6), p.47.

Kristol,

I., 1977. On corporate philanthropy. Wall

Street Journal, 21 March.

Lenzen,

M., Moran, D., Kanemoto, K, Foran, B., Lobefaro, L. and Geschke, A., 2012.

International trade drives biodiversity threats in developing nations. Nature, 486,

pp.109-112.

Lewis,

W., 1954. Economic development with unlimited supply of labour. In: A. Agarwala

and S. Singh, eds. 1954. The

Economics of Underdevelopment, Bombay: Oxford University Press.

pp.400–435.

McGann,

J., 2017. 2016 Global Go To Think Tank Index Report. [pdf] University of

Pennsylvania. Available at:

<http://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1011&context=think_tanks>

[Accessed 13 Aug. 2017].

Meadows,

D., Meadows, D., Randers., J. and Behrens III, W., 1972. The Limits to Growth.

New York: Universe Books.

Murray,

G., 2006. Capitalist networks and social

power in Australia and New Zealand. Hampshire, UK: Ashgate.

Nordhaus,

W., 1973. World dynamics: measurement without data. Economic Journal, 83, pp.1156–1183.

Packard,

V., 1959. The status seekers: an

exploration of class behavior in America. New York: David McKay.

Rignot,

E., Mouginot, J., Morlighem, M., Seroussi, H. and Scheuchl, B., 2014.

Widespread, rapid grounding line retreat of Pine Island, Thwaites, Smith, and

Kohler glaciers, West Antarctica, from 1992 to 2011. Geophysical Research Letters,

41(10), p.3502.

Rostow,

W., 1960. The stages of economic growth:

a non-Communist manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Solow,

R., 1973. Is the end of the world at hand? Challenge, March–April, pp. 39–50.

Solow,

R., 1974. The economics of resources or the resources of economics. American Economic Review,

64(2), pp.1–14.

Steffen,

W., Broadgate, W., Deutsch, L., Gaffney, O. and Ludwig, C., 2015. The

trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration. Anthropocene Review,

2(1), pp.81-98.

Steffen,

W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E., Biggs,

R., Carpenter, S., de Vries, W., de Wit, C., Folke, C., Gerten, D., Heinke, J.,

Mace, G., Persson, L., Ramanathan, V., Reyers, B. and Sörlin, S., 2015.

Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science, 347(6223).

Taylor,

M., Gwinnett, C., Robinson, L. and Woodall, L., 2016. Plastic microfibre

ingestion by deep-sea organisms. Scientific

Reports, 6, Article 33997.

Truman,

Harry, 1949. Inaugural address, 20 January. Harry S Truman Library and Museum.

Available at:

<http://www.trumanlibrary.org/whistlestop/50yr_archive/inagural20jan1949.htm>

[Accessed 20 Oct 2016].

Turner,

G., 2014. Is Global Collapse Imminent? [pdf] MSSI Research Paper No. 4,

Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, University of Melbourne. Available at:

<https://sustainable.unimelb.edu.au/sites/default/files/docs/MSSI-ResearchPaper-4_Turner_2014.pdf>

[Accessed 10 Aug 2017].

Voyer,

R. and Murphy, M., 1984. Global

2000: Canada, a view of Canadian economic development prospects, resources and

the environment. Toronto: Pergamon.

Watson,

R., Carraro., C., Canziani, P., Nakicenovic, N., McCarthy, J., Goldemberg, J.

and Hisas, L., 2016. The Truth About Climate Change. [pdf] Universal Ecological

Fund. Available at:

<http://www.ledevoir.com/documents/pdf/the_truth_about_climate_change.pdf>

[Accessed 19 Oct. 2016]

World

Wildlife Fund (WWF), 2014. Living

planet report. [pdf]

Available at:

<http://awsassets.panda.org/downloads/lpr_living_planet_report_2014.pdf>

[Accessed 13 Aug. 2016].

Zencey,

E., 2013. Energy as master resource. In: Worldwatch, ed. 2013. State of the World 2013: Is

Sustainability Still Possible? Washington, DC: Island Press. pp.73–83.