Agrowth instead of anti- and pro-growth: less

polarization, more support for sustainability/climate policies

First online: 1 October 2018

Jeroen

C.J.M. van den Bergh

Jeroen

van den Bergh is ICREA Professor at the Institute of Environmental Science and

Technology of Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (2007–present), and full

Professor of Environmental & Resource Economics at VU University Amsterdam

(1997–present). His research is on the interface of environmental economics,

energy-climate studies and innovation research. He is Editor-in-Chief of the journal Environmental Innovation and

Societal Transitions. He received the Royal/Shell Prize 2002 for

Sustainability Research, IEC’s Sant Jordi Environmental Prize 2011 and an ERC

Advanced Grant. His most recent book is Human

Evolution Beyond Biology and Culture: Evolutionary Social, Environmental and

Policy Sciences (Cambridge

University Press, October 2018).

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

DOI: 10.3197/jps.2018.3.1.53

Licensing: This article is Open Access (CC BY 4.0).

How to Cite:

van den Bergh, J.C.J.M. 2016. 'Agrowth Instead of Anti-and Pro-Growth: Less Polarization, More Support for Sustainability/Climate Policies'. The Journal of Population and Sustainability 3(1): 53–73.

https://doi.org/10.3197/jps.2018.3.1.53

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Abstract

An agrowth strategy, defined as being agnostic and indifferent

about GDP growth, is proposed as an alternative to unconditional anti- and

pro-growth strategies. It is argued that such a strategy can contribute to

reducing scientific and political polarization in the long-standing debate on

growth versus the environment. Hence, it can broaden urgently needed support

for serious sustainability and climate policies. The exposition includes a

novel graphical illustration, a summary of recent surveys of citizens and

scientists regarding support for an agrowth position, and a discussion of

implications for population growth and policies.

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to the editor, David

Samways, for careful reading and insightful comments.

1. Growth fixation as a barrier to

sustainability policies

Humanity

faces serious sustainability challenges but has been incapable so far of

implementing sufficiently strict policies that guarantee a sustainable course

of the economy. One important reason is that voters and politicians – fueled by

pessimistic environmental science studies – fear that serious policies will

hamper economic growth. Whether this will be the case or not is of no

relevance. What matters is the psychology behind it. If people cannot be

convinced that policies will not harm growth then such policies will not

receive majority support. Of course, one could respond by claiming that green

growth is possible, even though the evidence for this is weak. In fact, the

uncertainty surrounding this issue is immense and it is impossible to provide

definite proof of whether or not green growth is feasible. What we know for

sure is that current growth is not sustainable and that for a while, during a

transition phase, it will remain unsustainable. One way out of this dilemma is

to refrain from trying to convince voters and politicians that green growth is

possible. In fact, economists have been unsuccessful in persuading both groups,

otherwise good sustainability policies would have already been implemented. I

will propose here that we should become agnostic and indifferent about GDP

growth, i.e. adopt an agrowth position (van den Bergh, 2011). One

reason is that the GDP is not a good indicator of happiness or social welfare.

Another reason applies specifically to rich countries where for some time

increases in average income growth have not contributed to significant

increases in social welfare.

Climate

change illustrates the need for an ideological shift to agrowth (van den Bergh,

2017). The challenges posed by climate change and policies to tackle it have

revived the growth debate. Modern economies and lifestyles are highly dependent

on burning fossil fuels, generating CO2 emissions

responsible for global warming. If per capita GDP increases by 1.5% annually,

to realize the 2°C goal (supported by IPCC and the Paris Climate Agreement),

carbon intensity or emissions per unit of GDP should decrease by some 80% by

2050, which comes down to a 4.4% average annual improvement (Antal and van den

Bergh, 2016). Even if economic growth would come to a halt – i.e. in the case

of zero growth – still an impressive 67% intensity reduction, or 2.9% on

average per year, will be required. Since these reduction rates should be net

of all energy rebound (Sorrell, 2007) and carbon leakage effects (Felder and

Rutherford, 1993), they are merely lower bounds. Under serious climate policy

the rate of economic growth is thus likely to drop for some time, possibly

until we have reached a zero-carbon economy. Such a consequence will induce

fear for and opposition to associated climate policies in many advocates of

green growth. An agrowth strategy, on the other hand, will facilitate the

acceptance of these policies as it will free us from the unnecessary,

welfare-obstructing growth paradigm. This will result in removing false

trade-offs between GDP growth and other goals arising from the constraint of

always, at any time and under any conditions, having to achieve GDP growth.

2. We should abandon GDP but are

unable

A

large majority of economists, journalists and politicians, irrespective of

their political affiliation, express themselves uncritically about GDP and fail

to distinguish it clearly from (social) welfare. Nevertheless, a growing group

of economists, including many Nobel laureates, have explicitly accepted the

shortcomings of GDP (summarized in Table 1). Early critics included eminent

economists such as Kuznets (1941), Galbraith (1958) and Samuelson (1961). Later

influential voices are Mishan (1967), Nordhaus and Tobin (1972), Hueting

(1974), Hirsch (1976), Sen (1976), Scitovsky (1976), Daly (1977), Tinbergen and

Hueting (1992), and Arrow et al. (1995); more recent contributions come from

Frank (2004), Kahneman et al. (2004), Victor (2008) and Jackson (2009).

In

line with this, empirical research on happiness suggests that in most Western

(OECD) countries the increase in prosperity or happiness stagnated somewhere in

the period between 1950 and 1970 or even reversed to negative trend, despite

the steady growth in GDP per capita (Layard, 2005). This is supported by

empirical studies of alternative indicators of social welfare, such as the ISEW

(Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare) (Daly and Cobb, 1989). Moreover,

psychological research has found that individuals quickly become accustomed or

adapt to new conditions, including income increases, and as a result welfare

increases fall short of ex ante expectations (Easterlin, 1974).

Unfortunately,

the majority of economists are less critical and accept or even overtly support

the false idea that that GDP growth always means progress. They should realize

that both microeconomic and macroeconomic theories tend to formulate societal

goals in terms of social welfare not GDP or its change. In the standard

utility-maximizing behavioral model of microeconomics, income co-determines,

with prices, the budget constraint, rather than being a proxy for utility.

Likewise, in macroeconomics, growth theory is dominated by models of optimal

economic growth in which the guiding criterion is (intertemporal) social

welfare rather than an aggregate GDP type of income measure.

Table 1. Main shortcomings of

GDP as a proxy of social welfare

|

General |

Specific |

|

GDP use does not satisfy basic principles of good

bookkeeping |

– GDP does not

distinguish clearly between costs and benefits. – It does not

correct for changes in (economic and environment) stocks. – It does not

account for external (or social=private+external) costs. – It is an estimate

of the costs rather than benefits of market activities in a country. |

|

Using GDP (growth) as a proxy of social welfare (progress)

is inconsistent with the general welfare focus in microeconomics and

macroeconomics |

– Optimal growth theory

employs social welfare rather than GDP/income type of criteria. – In microeconomics,

income is part of the budget constraint, not a proxy of utility. – If income is not a

robust measure of welfare at the individual or micro-level, then aggregation

of individual incomes into GDP cannot result in a robust indicator of social

welfare. |

|

GDP does not capture stylized facts of empirical research

on subjective well-being (happiness) |

– Modern income

growth increases material consumption at the cost of basic needs like

serenity, clean air, and direct access to nature; the latter are, however,

not captured by GDP. – Somewhere between

1960 and the present, the increase in welfare stagnated or even reversed into

a negative trend in most Western countries, despite the steady pace of GDP

growth. – Individuals may

adapt or get used to changed circumstances, including a higher income; thus

well-being may temporarily change in response but then return to its baseline

level. |

|

GDP does not capture income inequality, relative income,

and status-seeking in consumption |

– GDP per capita

emphasizes average income, and neglects the income distribution, even though

this affects opportunities for personal development and well-being. – GDP does not

capture that individuals or families with low incomes benefit relatively more

from an income rise, because of the diminishing marginal utility of income. – Welfare is

relative or context-dependent, characterized by comparing oneself with

others, rivalry via “positional or status goods”. – As GDP omits

relative income aspects of welfare, it tends to overestimate social welfare

and progress. – Rises in relative

income and welfare come down to a zero-sum game: one individual loses what

another one gains; GDP cannot account for this. |

|

GDP neglects the informal economy, its share in the whole

economy, and its change |

– In general, GDP

just covers activities and transactions that have a market price and neglects

informal transactions between people that occur outside formal markets. – Actual GDP growth

sometimes reflects a transfer of existing informal activities (unpaid labor)

to the formal market; so the benefits were already enjoyed but the market costs

were not yet part of GDP. – This holds for

both developed and developing countries, and for such informal activities as

subsistence agriculture, voluntary work, household work, and child care. – The GDP can,

therefore, not serve as a measure to judge the welfare impact of fundamental

changes that involve a transition from informal to a formal activities |

|

GDP does not capture environmental externalities, damage

to ecosystems, and depletion of renewable and non-renewable natural resources |

– The presence of

externalities means that market prices do not reflect total social

(=private+external) costs, making them unreliable signals. GDP is, however,

calculated using these prices. – If air, water, or

a natural area are being polluted, any damage does not enter GDP, but when

pollution is being cleaned up this contributes to GDP. – Capital

depreciation associated with environmental changes (fish stocks, forests,

biodiversity) and depletion of resource supplies (fossil energy, metal ores)

is missing from the GDP calculation. As a result, GDP suggests we are richer

than we really are. |

Note: This table is reproduced from

van den Bergh (2017) and summarizes the survey in van den Bergh (2009).

So if this is all true, why do

so many influential people get nervous when there is little GDP growth? This

paradox (van den Bergh, 2009) can be explained by all of us constantly

receiving the message, through news media and in education, that economic

growth is imperative. Moreover, the response to low GDP growth from

politicians, economists, financial markets and international organizations like

the OECD (e.g., 2011), the World Bank (e.g., 2012), and the IMF is consistently

negative. They all signal that GDP growth is a sine qua non for our society. An

important additional reason is the widespread belief that GDP growth is a

necessary condition for economic stability and full employment. Empirical

evidence for this view is weak though, indicating that the relationship between

GDP and employment is not constant (Saget, 2000). Broadly accepted insights

about long-run equilibrium employment suggest that it depends more on search

time (jobs and employees); structural mismatches between education and work;

the difference between gross and net income; and the gap between income and

unemployment benefits (Pissarides, 2000). Moreover, the causality of growth and

employment is easily confused as more employment can increase GDP rather than

the reverse. In this respect, the “productivity trap”, coined by Jackson and

Victor (2011), is relevant. It denotes that growth compensates for potential

unemployment resulting from technological innovation driving labor productivity

improvements. This is possible as a higher labor productivity translates into

higher incomes, allowing for additional purchasing power to balance the larger

production capacity associated with productivity increases. This is, in a

nutshell, the fundamental mechanism driving economic growth. Incidentally, by

shifting taxes from income to environmental externalities one could redirect

technological change from improving the productivity of labor to that of energy

and material inputs to production. As a result, it would be easier to realize

full employment and environmental goals simultaneously.

3. Agrowth elaborated

An agrowth position

or strategy comes down to being agnostic about, i.e. ignoring, the GDP (per

capita) indicator in public debates and policymaking. It means we will be

indifferent, neutral or “agnostic” about the desirability of GDP growth, an

idea first proposed in van den Bergh (2011). The motivation is the insight that

unconditional growth implies an unnecessary and avoidable constraint on the

search for human welfare and progress. By definition, such a constraint hampers

the achievement of good public policies and decisions in any area, whether

social, health, labor, equity, education, environment or climate. This is

graphically illustrated by Figure 1 in van den Bergh (2017). One should note

that an agrowth position opposes unconditional GDP growth, also known as the

growth paradigm, but not growth per se.

Under an agrowth strategy,

periods of high, low, zero and even negative growth could alternate with one

another, as long as environmentally sustainability and progress in terms of

welfare were guaranteed. We would no longer give priority to average income

over welfare, or assume growth would be necessary or sufficient for progress.

While progress might sometimes coincide with growth, nobody would really care.

With regard to environmental pressures, an agrowth strategy would allow for

selective decline and selective growth of distinct economic and industrial

sectors which would not necessarily translate into aggregate GDP growth.

By ignoring GDP information, we

would in some periods be capable to give up potential GDP growth for a better

environment, less unemployment, more income equality, more leisure or better

health care. As a result, welfare-enhancing policy would be given priority over

GDP growth-enhancing policy. This would contribute to social-political acceptability

of public policies focusing on solving urgent and socially important problems

that are likely to reduce social welfare. Such an approach is consistent with

the advice by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman et al. (2004) to focus the

attention of public policy on minimizing unhappiness. Clear examples are

avoiding dangerous climate change, minimizing structurally high unemployment,

and reducing extreme inequality and poverty. Whether these policies would work

out well in terms of growth of GDP (per capita) would no longer be an issue.

Another advantage of an agrowth

strategy is that it increases economic stability and reduces the likelihood of

economic crises. The reason is that it weakens positive feedback in the economy

which contributes to business cycles and crises. As argued in Antal and van den

Bergh (2013), the current economic system is self-amplifying because a majority

of the connections between important economic system variables take the form of

positive feedbacks, while a minority of such connections takes the form of

negative feedbacks. A positive feedback denotes that an output of a system

enters the same system as an input, which then reinforces the actual trend in

the output. This is irrespective of whether the trend is a decline or a growth

pattern. In other words, positive feedback can generate negative and positive

spirals. Expectation about, and predictions of, GDP growth can be characterized

as being pro-cyclical, in the sense that if it is widely believed that such

information has a significant influence on reality, then, through pessimistic

(or optimistic) reactions to negative (positive) growth expectations, these

beliefs become self-fulfilling. This sets in motion positive feedback

affecting, among others, consumer expenditures and savings, firm expenditures

and investments, which result in economic instability.

Positive feedback assures that,

as long as we are on the upward trend, there is optimism about the economy. If,

though, growth weakens and expectations are not met, pessimism about future GDP

growth starts to set in, potentially leading to a recession. Two common

solutions are offered by Keynesian and monetarist or new classical[1] schools of macroeconomics. The first

recommends stimulating aggregate demand by increasing public spending or

lowering taxes. The second proposes austerity and debt reduction to restore

confidence. These strategies, although polar opposites, share the goal of restoring

the upward economic spiral driven by positive feedback. And in environmental

terms, both put their full confidence in green growth. Instead, an agrowth

strategy tackles a fundamental positive feedback mechanism underlying economic

instability, namely the role of GDP information. By suggesting to ignore the

GDP indicator, it weakens positive feedback in the economy, resulting in a more

stable economy. This will discourage extremely high growth rates but also lower

the probability of recessions.

Antal and van den Bergh (2013)

discuss a long list of options to weaken other positive feedbacks and

strengthen or create negative feedbacks, with the aim to improve economic

stability. One recommendation is to replace the GDP by another indicator, such

as the Human Development Index, an income inequality measure (Gini index or

median income), or an ISEW-type of proxy of social welfare (Daly and Cobb,

1989). Another idea is to construct an index that is an average of a minimum,

medium and mean income, as it results in a monetary indicator that captures

income inequality well (van den Bergh, 2017a).

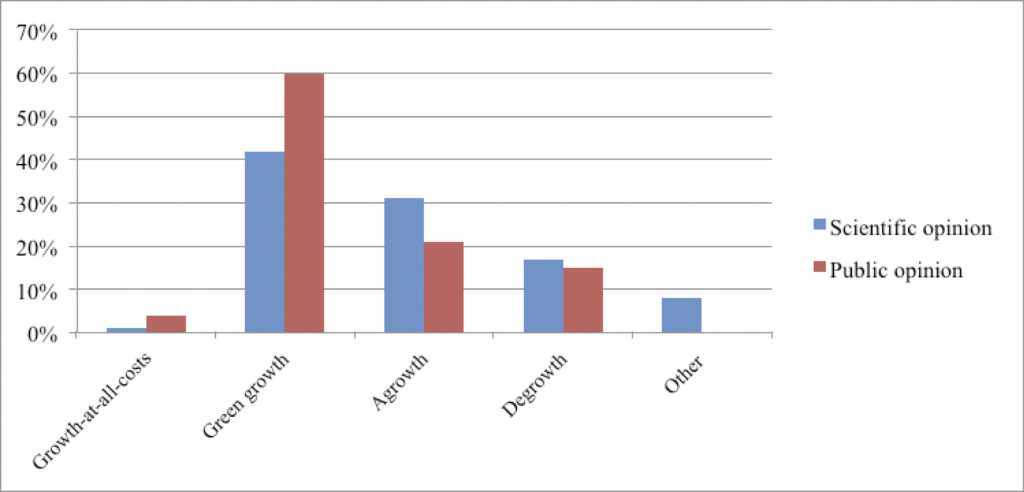

Empirical evidence suggests

that agrowth may count on reasonable support, which means it could depolarize

the debate on growth-versus-environment. Figure 1 depicts results from two

questionnaire surveys, among scientists and citizens. While green growth is the

most popular position, scientists express relatively more support for agrowth

and less for green growth than citizens. With more discussion of a recent and

new idea like agrowth one might expect support for it to increase.

Source: Drews and van den Bergh (2019). Data from Drews and van

den Bergh (2016 and 2017).

Figure 1. Scientists’ versus citizens’ preferences for a public

policy strategy regarding growth and the environment

4. Riskiness of pro- and anti-growth strategies

The historical debate on growth

versus the environment is often summarized as between optimists believing in

limitless growth and pessimists seeing environmental and natural resource

limits to growth. This opposition best defines the main policies and strategies

found: namely, striving for green growth by decoupling income and production

from environmental pressure versus an anti-growth approach taking the form of

stopping growth (zero-growth) for the sake of the environment. However, a more

subtle classification of viewpoints in the growth debate is possible, such as

the five perspectives identified by van den Bergh and de Mooij (1999): a

moralist, denying the relevance of further growth for individual and social

welfare, notably in rich countries; a pessimist, stressing environmental and

resource limits to growth; a technocrat, seeing markets and technological

progress as powerful mechanisms to relieve any existing limits; a sceptic,

assessing economic growth and environmental ruin as both unavoidable; and an

optimist, considering growth as a requirement for solving environmental

problems since it makes citizens more concerned about the environment.

Even though many economists and

international organizations express a strong belief in green growth, few

politicians demonstrate that they share this belief through their actual

decisions. Instead, they signal fear that serious climate policies will reduce

the rate of economic growth. This suggests that economists have not provided

sufficiently convincing evidence for the feasibility of green growth. This is

no surprise, as the future is uncertain, and we have not yet succeeded in

applying all the policy conditions that guarantee a sustainable economy, hence

we do not know if such an economy could steadily grow in GDP terms. Theory says

both outcomes are possible (Acemoglu et al., 2012). If green growth is not

feasible, however, any strong messages about its realization will create false

hopes. As a result, one will harm either the environment or economic stability.

Recently, a particular

expression of anti-growth has appeared: so-called “degrowth” has the explicit

aim of downscaling the economy to meet environmental goals (Schneider et al.,

2010; Kallis, 2011). It can be interpreted as complicating climate policy with

a quest for radical change. Degrowth is unlikely to be an effective strategy

for creating broad political support given that it focuses on variables with an

indirect link to emissions, instead of on the carbon content of growth, in

addition to its basic message that we need income and other sacrifices to save

the environment (Drews and Antal, 2016). Furthermore, as degrowth does not

follow a clear welfare approach and is not focused on sharply distinguishing

between low-carbon and high-carbon consumption, it runs the risk of destroying

too much welfare for the purpose of sustainability, without even guaranteeing

an effective, let alone a cost-effective, way of solving sustainability

problems. For instance, the degrowth proposal does not offer a clear framework

for satisfactorily balancing – from a welfare perspective – changes in inputs

(e.g., fuels), energy efficiency of technologies, composition of production and

consumption, and volume or scale of activities. Any physical or GDP degrowth

goal will then be arbitrary and debatable. Another shortcoming is that the term

“degrowth” is defined and used differently by distinct authors. One can identify

at least five interpretations (van den Bergh, 2011), namely as GDP decline,

less consumption (unclear how measured), a work-time reduction, a smaller

physical size of the economy, and a radical move away from “capitalism” and

markets. Such ambiguity does not contribute to productive societal or

scientific exchange. The proposal for degrowth is likely to contribute to

polarization, creating sharp differences between supporters and opponents of

degrowth. If we sell climate solutions as degrowth, then support for these is

likely to diminish rather than rise over time.

Instead, an agrowth strategy

can, because of its neutrality and indifference regarding GDP growth, bridge

pro-growth and anti-growth views and so reduce polarization. In fact, I have

many personal experiences with degrowth and green growth believers expressing

support for the agrowth position. To see why it can bridge the divide, one

should recognize that agrowth does not preclude GDP growth when it is feasible

and improves human welfare, and neither rejects GDP decline when an outcome of

good social or environmental policies. In view of this, an agrowth strategy has

the potential to create and amplify the political space for balancing distinct

components of social welfare, such as consumption, employment, environment,

leisure, health, and inequality. In particular, agrowth will make it easier to

sell serious climate policy to the public and politicians, much easier than

selling degrowth. In addition, by tempering preoccupation with continued GDP growth,

it will moderate panic that is common among economists, journalists and

politicians when GDP growth slows down. In other words, an agrowth strategy

contributes to economic stability.

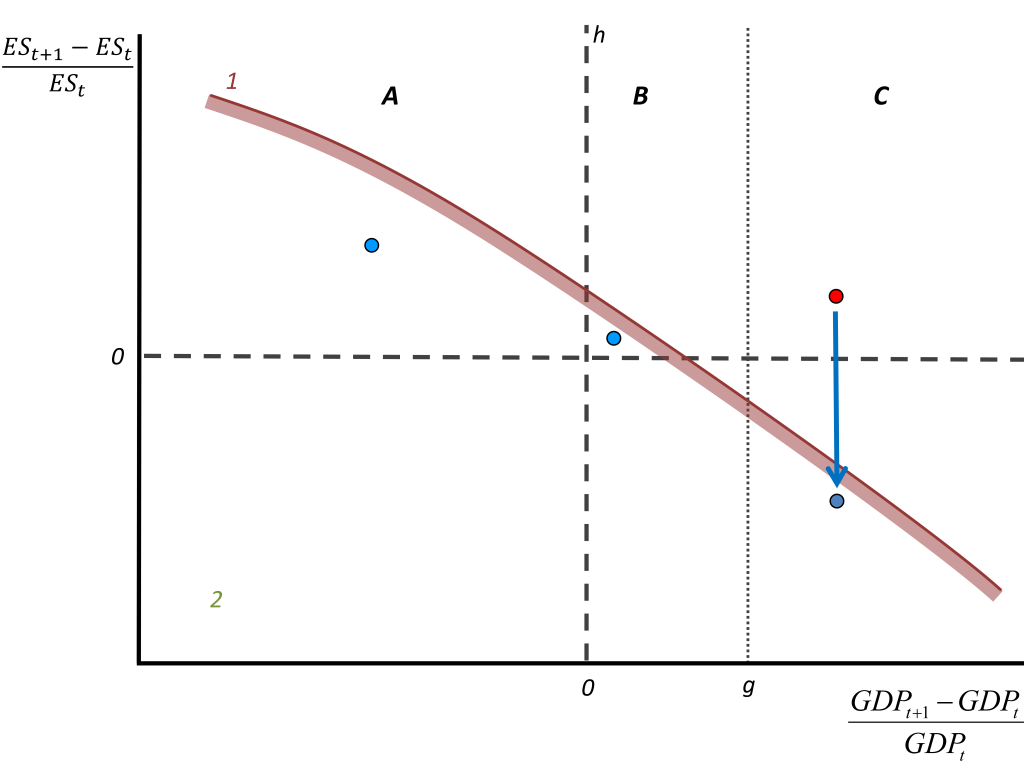

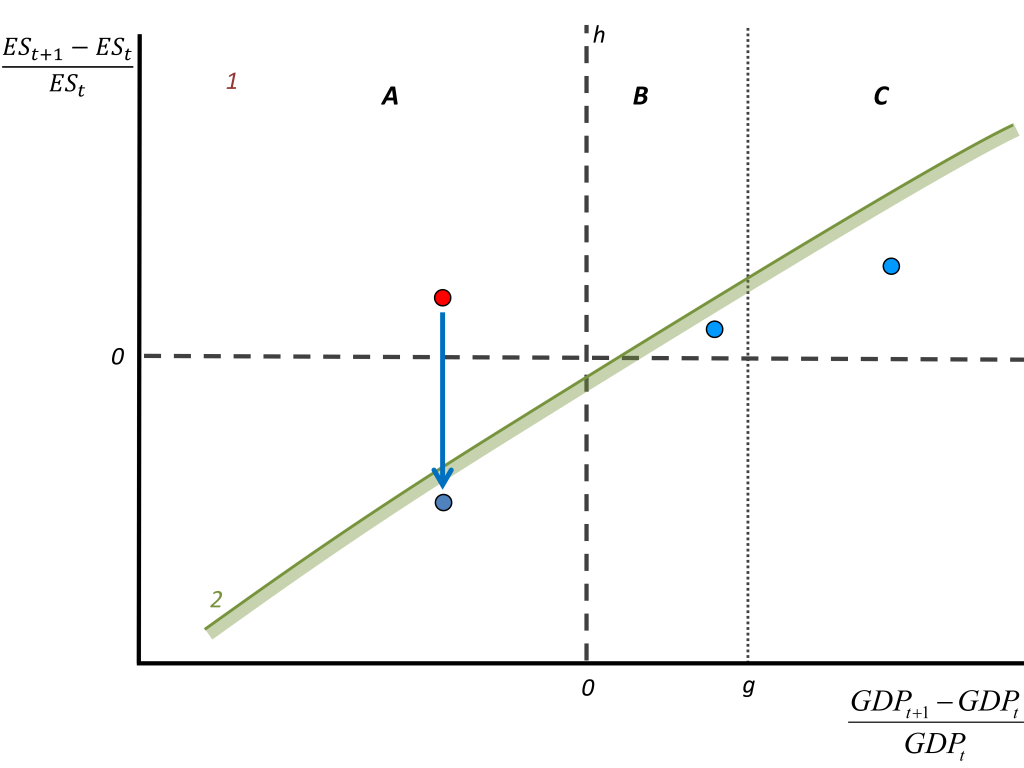

Figures 2 and 3 graphically

illustrate that an agrowth strategy, i.e. indifference about where on the

horizontal axis (indicating the rate of GDP growth) the economy is positioned,

is robust against uncertainty about the relationship (curve 1 versus 2) between the GDP growth rate (horizontal axis) and the change in

other components of human welfare including environmental sustainability (ES)

(vertical axis). It is assumed here that environmentally desirable outcomes

require being positioned above the horizontal 0 (zero) line, meaning that no reductions in

environmental performance are accepted. Hence, a degrowth strategy strives to

be in (rectangular) area A,

a zero-growth strategy on the top (positive) part of vertical line h, a low growth strategy in (rectangular) area B, and a high-growth strategy in (rectangular) area C (where

growth is higher than rate g,

such as the often expressed desire of at least 2% growth). However, an agrowth

strategy does not exclude any of these areas.

Now, a pessimistic perspective

on the growth-vs-environment relationship is shown in Figure 2 through a

downward-sloped curve 1 that represents the upper bound to feasible

combinations of changes in GDP and ES,

while Figure 3 displays an optimistic perspective through an upward-sloped

curve 2.

Consider first Figure 2, where a green growth strategy aiming for growth beyond

the rate g is not wise as it will not achieve its aim of

ending up in area C.

The reason is illustrated by the red position above the constraint 1which represents an infeasible goal. If one strives for high

growth associated with it, the economy will end up in the blue point below the

constraint (following the arrow). In this case degrowth (area A) and low growth (area B)

strategies are feasible. On the other hand, in the case depicted in Figure 3, a

high growth strategy is feasible but a degrowth strategy not because while

environmental impacts get lower, it becomes increasing difficult to sustain

human welfare. Indeed, trying to be in area Afails

here as one will be forced to be below constraint 2, indicated by an arrow from the red goal to the blue realization.

Hence, unlike an agrowth strategy that is tolerant to any outcome (positive,

zero or negative GDP growth, or areas A, B and C), neither growth and degrowth strategies are robust or

precautionary in the face of uncertainty about the conflict between growth and

environmental sustainability (represented by uncertainty about whether curve 1 or 2 holds

true). For further discussion, see van den Bergh (2017).

In conclusion, both green

growth and degrowth lack credible empirical support and make debatable

assumptions. These limitations make either of them risky strategies in solving

environmental and climate change problems, as well as more generally in

realizing progress in terms of social welfare. We do not need to assume that

growth and environment are conflictive or compatible. Recognizing uncertainty

about the future and complexity of the economy warrants being precautionary –

making an agrowth strategy the better response.

Note: Search space for human progress spanned by relative changes

in GDP & ES in interval [t, t+1]; bold letters denote the rectangles separated by the vertical and

horizontal broken lines.

Figure 2. Growth strategy fails in case of conflict between growth

and environmental sustainability, while degrowth and agrowth strategies remain

within feasibility area indicated by area below brown curve 1.

Figure 3. Degrowth strategy

fails in case of no conflict between growth and environmental sustainability,

while agrowth and growth strategies remain within feasibility area indicated by

area below green curve 2.

5. Climate change and population growth

Climate change is also affected

by population growth, while income GDP growth affects both of them in different

directions with an uncertain net outcome, depending on the country and other

factors. On the one hand, before we have made a transition to low-carbon

technologies, economic growth will increase emissions directly. On the other

hand, increasing income goes along with a demographic transition in certain

parts of the developing world, leading birth rates to go down due to, among

other factors, a fall in infant mortality leading parents to recognise that

fewer births will meet their needs in old age, urbanization, improved education

of women and access to contraception (Chesnais, 1992). An agrowth position does

not deny the need for economic growth so a scenario where growth contributes to

demographic transitions in some countries (notably in sub-Saharan Africa) may

be an outcome. In rich countries with low or no population growth, however, low

economic growth is more likely as a transition scenario before a low-carbon

economy is achieved. For some middle-income countries with high birth rates the

trade-off is less clear beforehand and the net effect of economic growth on

emissions, taking population effects into account, may be either positive or

negative. An agrowth strategy is consistent with such a diversity of growth

strategies in different countries, notably poor and rich ones, unlike a green

growth position which requires high growth in all countries, denying national

diversity of potential and need for growth. Note that agrowth as a strategy

does not apply to population directly. Instead, population growth worldwide

needs to be stopped as soon as possible to avoid further overshooting of the

human economy, including with regard to global warming.

A recent account of the link

between climate and population and adequate policies is provided by Bongaarts

and O’Neill (2018). They argue against various misperceptions, such as that

population growth is under control and does not matter much for climate change,

and that population policies are ineffective and too controversial to succeed.

Possibly, the worst decision one can make in terms of climate-change

externalities is not to buy a product or service but to have a child (Harford,

1998; Wynes and Nicholas, 2017), unless during its life-time it will invent

some cheap zero-emission technology that will change the world. It implies

additional emissions over the entire lifetime of a child, decades into the

future. With a growing number of people on Earth, the carbon budget associated

with a safe climate is quickly exhausted. In view of this, some have proposed,

in addition to a tax on the carbon content of energy, goods and services,

so-called birth taxes (Kennedy, 1995). One argument why the decision of having

a child should be regulated or priced separately is that parents make this

decision while arguably only accounting for their own welfare effects and

neglecting any social or environmental costs generated by the child in the

future. Moreover parents may be insufficiently rational to perceive all private

costs of raising children until adulthood. In addition, the desired number of

children will be influenced by the culture and religion to which parents

belong. Parents will thus be unable to respond rationally or optimally to the

sum of private and social costs (as captured by the carbon tax), suggesting

that birth regulation is required as well to assure that climate goals are

reached. The magnitude of this is not insignificant: Bohn and Stuart (2015)

calculate that an optimal child tax equals 21.1% of a corrected per capita

income during the time span of a generation. They illustrate this for the USA,

noting that the relevant income measure was on average ± $48,000 per adult per

year during the study period, which translates into a child tax of about

$10,000 per year during a period of 30 years from birth on. Hence, over the 30

year period the undiscounted sum of annual taxes would amount to $300,000.

Implementation of such a policy would arguably also contribute to reducing

poverty in the next generation as a larger share of people would be the

offspring of relatively rich families who could more easily afford a child tax

(even though it would be higher in absolute terms), offering a better start in

life in terms of wealth and education. Although such a child tax is sure to

meet ethical and political resistance, one should recognize its unique capacity

to simultaneously address climate, overpopulation and long-term poverty

challenges. Moreover, the associated tax revenues could be used to reduce

existing income taxes so as to limit the overall tax burden for households

which might simultaneously increase employment (Freire-González, 2018).

Incidentally, an alternative for a child tax with similar consequences would be

a system of tradable birth permits (a combination of regulation and market

mechanism), as proposed by Boulding (1964) and elaborated by Daly (1977) and

others (see references in De La Croix and Gosseries, 2009).

6. A transition to an agrowth paradigm

One cannot be optimistic about

changing the current growth paradigm, but it is worth trying as the permanent

focus of our society and politicians on GDP growth forms a barrier to urgently

needed sustainability policies. The fear that stringent climate policies will

frustrate future economic growth is an important reason for many voters and

politicians to be reluctant to genuinely support such policies. This partly

explains why the Copenhagen climate summit failed and the recent Paris

agreement was designed around voluntary national climate targets rather than

globally harmonized policies. The discussion about climate versus growth will

probably intensify in the coming years now that the time available to limit

global warming is shrinking and serious emissions reductions are still awaited.

The literature on

growth-versus-climate shows that theoretical and empirical support for both

green growth and anti-growth is weak. Both strategies are risky and do not

provide sufficient guarantee for managing climate change or other

sustainability challenges. These strategies are also incompatible with a focus

on social welfare in normative micro and macroeconomic theories. A third,

neutral or indifferent vision called agrowth is more reasonable. It will create

a broader basis of support for stringent climate policies as it will

de-polarize the growth debate by bridging the opposition between green growth

and anti-growth positions. In contrast to pro-growth, the agrowth strategy does

not give priority to income growth over the climate, but is aimed at finding a

genuine balance between all aspects of social welfare. That is why it will

provide more political scope for effective climate policy, as well as for a

fair income distribution. In response to uncertainty about whether to be

optimistic or pessimistic about sustainable growth, one can follow a

precautionary strategy by being agnostic and being resilient to all possible

options.

Since the unconditional

pro-growth strategy is dogmatic in nature, change to a new agrowth paradigm

will be difficult. Current politics is characterized by nervous reactions to

low GDP growth. The preoccupation with GDP growth is invigorated by repetition,

in both education and the media, of the erroneous idea that growth is necessary

or even sufficient to solve important social problems. Higher economic growth

has also been shown to increases the likelihood that government leaders will

stay on longer (Burke, 2012). Hence, the pressure on politicians to be guided

by unconditional economic growth is unfortunately still great. If change does

occur, it is likely to come in stages, such as: first social sciences, then

economics, then politics and then voters.

Notes

[1] Aimed

at establishing neoclassical microeconomic foundations for macroeconomic

analysis.

References

Acemoglu, D., Aghion, P.,

Bursztyn, L. and Hemous, D., 2012. The environment and directed technical

change. American Economic Review102(1):

131-166.

Antal, M., and van den Bergh,

J.C.J.M., 2013. Macroeconomics, financial crisis and the environment: Strategies

for a sustainability transition. Environmental Innovation and

Societal Transitions 6:

47-66.

Antal, M., and van den Bergh,

J.C.J.M., 2016. Green growth and climate change: Conceptual and empirical

considerations. Climate Policy,

16(2): 165-177.

Arrow, K.J., Bolin, B.,

Costanza, R. Dasgupta,, P., Folke, C., Holling, C. S., Jansson, B.-O., Levin,

S., Mäler, K.-G., Perrings, C. and Pimentel, D., 1995. Economic growth,

carrying capacity, and the environment. Science 268(April 28): 520-21.

Bohn, H., and Stuart, C. 2015.

Calculation of a population externality. American Economic Journal:

Economic Policy 7(2):

61–87.

Bongaarts, J. and O’Neill,

B.C., 2018. Global warming policy: Is population left out in the cold? Science 361(6403):

650-652.

Boulding, K. E., 1964. The meaning of the twentieth century.

London: Allen & Unwin, Ltd.

Burke, P., 2012. Economic

growth and political survival. The B.E. Journal of

Macroeconomics 12(1):

1-43.

Chesnais, J.-C., 1992. The demographic transition: Stages, patterns, and economic

implications. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Daly, H.E., 1977. Steady-state economics: The political economy of biophysical

equilibrium and moral growth. San

Francisco: W.H. Freeman.

Daly, H.E., and Cobb, W., 1989, For the common good: redirecting the economy toward community, the

environment and a sustainable future. Boston: Beacon Press.

de la Croix, D., and Gosseries,

A., 2009. Population policy through tradable procreation entitlements. International Economic Review 50(2): 507–542

Drews, S., and Antal, M., 2016.

Degrowth: A “missile word” that backfires? Ecological Economics 126: 182-187.

Drews, S., and van den Bergh,

J.C.J.M., 2016. Public views on economic growth, the environment and

prosperity: Results of a questionnaire survey. Global Environmental Change 39: 1-14.

Drews, S. and van den Bergh,

J.C.J.M., 2017. Scientists’ views on economic growth versus the environment: a

questionnaire survey among economists and non-economists. Global Environmental Change 46, 88-103.

Easterlin, R.A., 1974. Does

economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David

and M. W. Reder, eds. 2014, Nations and households in

economic growth: Essays in honour of Moses Abramowitz. New York: Academic Press.

Felder, S., and Rutherford,

T.F., 1993. Unilateral CO2 reductions and carbon leakage: The

consequences of international trade in oil and basic materials. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 25: 162-176.

Frank, R.H., 2004. Positional

externalities cause large and preventable welfare losses. American Economic Review 95(2): 137-141.

Freire-González, J., 2018.

Environmental taxation and the double dividend hypothesis in CGE modelling

literature: A critical review. Journal of Policy Modeling 40(1): 194-223.

Galbraith, J.K., 1958. The affluent society. Boston: Houghton Mifflin

Company.

Gordon, R.J., 2012. Is U.S. economic growth over? Faltering innovation confronts the

six headwinds. [pdf] NBER Working Paper No. 18315. Available at: <http://www.nber.org/papers/w18315>

[Accessed 1 August 2018].

Harford, J. D., 1998. The

ultimate externality. American Economic Review88(1):

260–265.

Hirsch, F., 1976. Social limits to growth. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Hueting, R., 1974. Nieuwe schaarste and economische groei.

Amsterdam: Elsevier. (English edition 1980, New scarcity and economic

growth. Amsterdam: North-Holland. ).

Jackson, T., 2009, Prosperity without growth—economics for a finite planet.

London: Earthscan.

Jackson, T., and Victor, P.,

2011. Productivity and work in the ‘green economy’. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 1: 101-108.

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A.,

Schkade, D., Schwarz, N. and Stone, A., 2004. Toward national well-being

accounts. American Economic Review,

Papers and Proceedings 94:

429-434.

Kallis, G., 2011. In defence of

degrowth. Ecological Economics 70(5): 873-880.

Kennedy, J., 1995 Changes in

optimal pollution taxes as population increases. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 28(1): 19–23.

Kuznets, S., 1941. National income and its composition 1919–1938. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Layard, R., 2005. Happiness: Lessons from a new science.

London: Penguin.

Mishan, E.J., 1967. The cost of’ economic growth. London: Staples Press.

Nordhaus, W. D. and Tobin, J.,

1972. Is growth obsolete? In: Economic Growth.

New York: National Bureau of Economic Research, General Series No. 96. pp.1-80.

OECD, 2011. Towards Green Growth. Paris: OECD.

Pissarides, C.A.. 2000. Equilibrium unemployment theory (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Saget, C., 2000. Can the level

of employment be explained by GDP growth in transition countries? Theory versus

the quality of data. Labour 14(4): 623-643.

Samuelson, P.A., 1961. The

evaluation of social income: capital formation and wealth. In: F. Lutz and D.

Hague, eds. 1961, The Theory of Capital. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Schneider, F., G. Kallis and

Martinez-Alier, J., 2010. Crisis or opportunity? Economic degrowth for social

equity and ecological sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production 18(6): 511-518.

Scitovsky, T., 1976. The joyless economy. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Sen, A., 1976. Real national

income. Review of Economic Studies 43(1): 19-39.

Sorrell, S., 2007. The rebound effect: an assessment of the evidence for economy-wide

energy savings from improved energy efficiency.

[pdf] UK Energy Research Centre. Available at:

<http://www.ukerc.ac.uk/Downloads/PDF/07/0710ReboundEffect> [Accessed 1

August 2018].

Tinbergen, J., and Hueting, R.,

1992. GNP and market prices: wrong signals for sustainable economic success

that mask environmental destruction. In: R. Goodland, H. Daly and S. El Serafy,

eds. 1992. Population, Technology and

Lifestyle: The Transition to Sustainability.Washington D.C.: Island Press.

van den Bergh, J.C.J.M., and de

Mooij, R.A., 1999. An assessment of the growth debate. In: J.C.J.M. van den

Bergh, ed. 1999. Handbook of Environmental and

Resource Economics. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. pp. 643-655.

van den Bergh, J.C.J.M., and

Drews, S., 2019. Green “agrowth” – the next development stage of rich

countries. In Roger Fouquet ed. 2018. Handbook on Green Growth.

Cheltenham: Edward Elgar (forthcoming).

van den Bergh, J.C.J.M., 2009.

The GDP Paradox. Journal of Economic Psychology 30(2): 117-135.

van den Bergh, J.C.J.M., 2011.

Environment versus growth – A criticism of “degrowth” and a plea for

“a-growth”? Ecological Economics 70(5): 881-890.

van den Bergh, J.C.J.M., 2017a.

A third option for climate policy within potential limits to growth. Nature Climate Change, 7 (February),

107–12.

van den Bergh, J.C.J.M., 2017b.

Green Agrowth: Removing the GDP-growth constraint on human progress. Chapter 9

in: P.A. Victor and B. Dolter (eds.), Handbook on Growth and Sustainability.

Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp. 181-210.

Victor, P.A., 2008. Managing without growth. Slower by design, not disaster.

Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Weitzman, M.L., 1976. On the

welfare significance of national product in a dynamic economy. Quarterly Journal of Economics 90: 156-162.

World Bank, 2012. Inclusive Green Growth – The Pathway to Sustainable Development.

Washington D.C.: The World Bank.

Wynes, S., and Nicholas, K.A.,

2017. The climate mitigation gap. Environmental Research Letters 12(7), 074024.