Editorial introduction

Vol. 4, No. 2

First online: 18 June 2020

David

Samways

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

DOI: 10.3197/jps.2020.4.2.5

Licensing: This article is Open Access (CC BY 4.0).

How to Cite:

Samways, D. 2016. 'Editorial introduction'. The Journal of Population and Sustainability 4(2): 5–15.

https://doi.org/10.3197/jps.2020.4.2.5

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

The

eighth issue of the JP&S is published in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis.

The JP&S will in due course have a special issue devoted to the role of population

in pandemic risk, but for the present it is worth reflecting on how COVID-19

and global pandemics in general relate to population and environmental issues

and in particular to some of the themes covered by the papers (mostly written

well before the pandemic) in this issue.

The

immediate impact of the pandemic and its management have rightly been the focus

of concern, but the factors which led to the generation of the pandemic itself

are also of great importance given the costs in terms of both human health and

disruption to the lives of billions of people. The causes of the pandemic are

multiple, but population growth and density are amongst the most significant.

Along with specific consumption factors, the globalisation of the world economy

and other elements of our socio-technical systems, the ever-growing

entanglement of human populations with wild species has played a pivotal role

in the generation of the current crisis.

As

Ilan Kelman points out in his paper published here, the current pandemic is,

like many so-called ‘natural’ disasters, not ‘natural’ at all but the result of

our societal choices. In the case of COVID-19, the choices which have been

significant are not limited to how we have dealt with the spread of the

disease, but also include choices made in other spheres such as the economy,

international development, socio-technical structures and so on that formed the

unacknowledged conditions which facilitated the generation of the pandemic

itself. At the micro level, many of these ‘choices’ may have been

passively made, the outcome of deeply embedded social practices and ways of

life, the taken-for-granted aspects of everyday life. For many of those whose

direct entanglement with the natural world exposes them to zoonotic reservoirs,

the social practices in which they are engaged are frequently well beyond the

level of active choice. It is often the rural poor of the Global South who are

most exposed as population growth and poverty lead them to clear forest and

establish subsistence cultivation only to be later displaced by commercial

interests (Carr, 2009; Lopez-Carr and Burgdorfer, 2013; Kong et al., 2019).

The

trade in wildlife for bushmeat, traditional “medicines” and other cultural

practices is also a factor in the spread of zoonoses. COVID-19 is believed to

have originated in bats with the Malaysian pangolin, trafficked for use in

traditional Chinese medicine, as an intermediary species (Ye et al. 2020; Wong

et al. 2020). Among the many factors identified as drivers of the illegal wildlife

trade, economic growth and globalisation are critical. In more developed

countries the combination of population growth, urbanisation and increased

affluence has fuelled demand while in poorer regions population growth and

rural poverty are drivers of supply. Importantly, supply and demand have been

connected by improved roads to formally inaccessible wilderness locations and

trade routes to far away markets (Wolfe et al. 2005; Nijman, 2010; Rosen and

Smith; 2010).

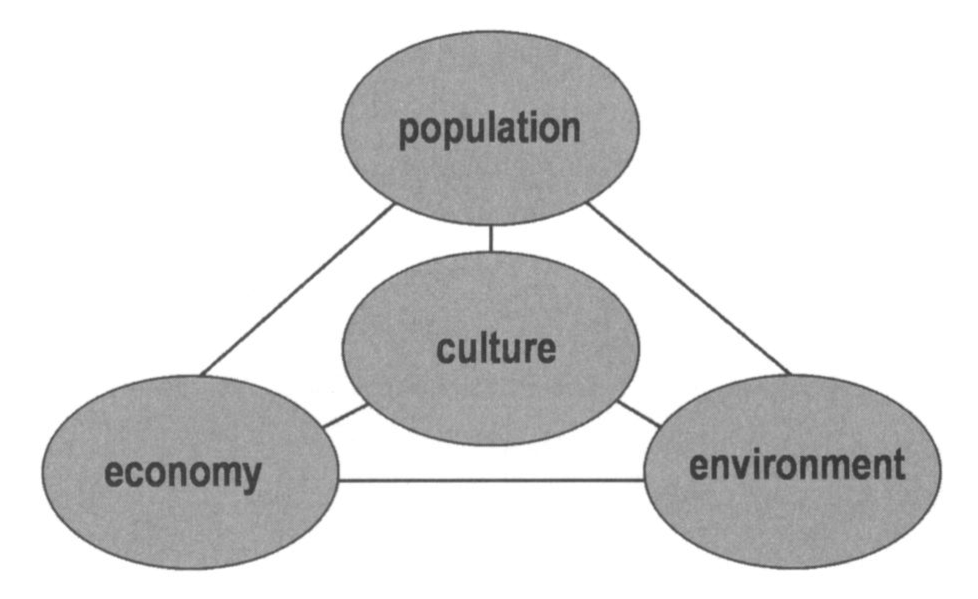

However,

it would be mistaken to regard population, consumption (affluence), and

technology (transportation systems)[1] as

simple drivers of our entanglement with nature and its associated risks. As

Joel Cohen (2017) has argued, culture is a critical factor in how population,

the economy and the environment articulate with each other (Fig. 1). Duffy et

al. (2016) have argued that in respect of the hunting of endangered wildlife,

poverty[2] has

been poorly conceptualised and that the motivations of individuals and social

groups to hunt have frequently been reduced to an economic rationality.

However, as they demonstrate, motivations for hunting often arise from deeply

embedded social and cultural factors and that policies aimed at reducing

hunting through financial incentives frequently fail or even unintentionally

increase the ability to hunt or consume bushmeat.

Figure 1. Joel E. Cohen’s

(2010) tetrahedron conceptualising the interactions between population,

environment, economy and culture.

As a

driver of human entanglement with nature, population growth itself also has

important socio-cultural dimensions which are not generally modelled in

standard demographic transition approaches where economic development is seen

as the primary determinant of reduced fertility. In addition to the

availability of sexual health services, female education, and the general

reduction in poverty, social norms surrounding family size are an important

determinant of fertility (Dasgupta and Dasgupta 2017). Influencing these social

norms and fertility choices can take a variety of forms and social marketing

methods have been employed successfully by the Population Media Centre (see

Ryerson 2018) and are the subject of Sarah Baillie, Kelley Dennings and

Stephanie Feldstein’s article on the Centre for Biological Diversity’s (CBD)

Endangered Species Condom project in this issue.

As

Baillie et al. show, social marketing is a means of “selling a social good as

if it were a commodity”. This structured, theoretically informed, approach has

been successfully employed to address a range of social problems (notably to

increase contraceptive use in India) and is employed by CBD not just as a means

of reducing unplanned pregnancy in the US, but also to start a conversation

about the impact of population growth on endangered species. Innovatively,

Endangered Species Condoms use humour and art to connect sexual health choices

with native wildlife species which are threatened directly by population

growth. CBD recognises that in the US population growth is largely a

consequence of immigration, but while the project is aimed at local

reproductive choices the objective is global in that the project elevates the

environmental consequences of population growth in public discourses with the

aim of ultimately influencing policy makers and, equally importantly, the

environmental NGOs which generally choose to ignore the issue.

Ilan

Kelman’s paper is concerned with the ability of society to cope with disaster.

He argues that the vulnerability of a society to the environment or nature is

consequent on societal choices which place people in harm’s way. Demographic

factors including population density can have both positive and negative

effects. While high density urban areas are more likely to have emergency

services that are experienced and well equipped, larger and more closely confined

populations, as in the case of COVID-19, can exacerbate risks. As Jenny

Goldie’s review of Doug Kelbaugh’s Urban Fix(published

here) makes clear, the redesigning of the city may well offer opportunities for

mitigating climate change and overpopulation. However, Kelbaugh’s enthusiasm

for high density urban living may be in question following the pandemic. With

population density being a key factor in the spread of the virus, many who have

become acclimatised to home working may well be reassessing the advantages,

costs and risks of urban living.

Worldwide,

populations are moving from rural to urban locations and it is this internal

migration that accounts for the majority of all the world’s migration (IOM

2020). Currently, just over half the global population live in urban areas, but

it is anticipated that by 2050 this number will rise to 68% (UN, 2018). The

COVID-19 pandemic has made the extent of internal migration extremely clear as

migrant workers lose their livelihoods and, en masse, have been forced to

return to their region of origin. The International Labour Organisation

estimates that 1.6 of the 2 billion people who work in the world’s informal

economy (nearly half the global workforce) have been severely affected by the

pandemic lockdown. The majority of these workers are in the Global South with

women being disproportionately affected compared to men (ILO, 2020).

This

latter aspect of the consequences of the pandemic chimes well with Ilan

Kelman’s observations regarding the gendered dimensions of disasters. In terms

of fatalities men appear to be disproportionately affected by COVID-19 (Jin et

al. 2020), but evidence suggests that in social and economic terms women will

be disproportionately affected (ILO, 2020; UN, 2020). Kelman argues that it is

gender differentiated roles rather than inherent qualities that frequently make

women more vulnerable to disasters. This is certainly the case with the

consequences of COVID-19: women generally earn less and save less than men,

they are often in more insecure employment, are more likely to be heads of

single parent households, the burden of unpaid care work largely falls on them,

and on top of this they are more likely to experience greater levels of

domestic violence during lockdown. From the perspective of population growth

the disruption to sexual health services may result in increased fertility. In

the Caribbean and Latin America it is estimated that 18 million women will lose

regular access to contraception as a result of the pandemic (UN, 2020). The

disruption to sexual health services represents an immediate threat, but the

economic impact upon women in the Global South represents a longer-term risk of

stalling the progress made on increasing fertility choices.

The

role of internal migration on urban expansion and population density are themes

of Ripan Debnath’s contribution to this issue. Exploring the effect of land use

change on local climate in Dhaka, Bangladesh, Debnath models the impact of

rural to urban migration on the rapid growth in Dhaka city and shows, through

the analysis of satellite images and geographic, demographic and climatic data,

that such growth will adversely impact the future urban climate. While

influenced by global and regional climate change, local land cover change will

be an additional exacerbating factor. Land use change from agricultural to

urban will result in both heat stress and flooding which will

disproportionately affect the most recent and poorest migrants who tend to live

in low-lying areas. Like Kelman and Kelbaugh, Debnath argues that the worst

effects of such disasters can be avoided with the right urban planning policy

choices. However, like Kelbaugh, Debnath sees so called ‘smart growth’

principles involving, amongst other things, higher density development as a

possible solution to Dhaka’s population growth. Undoubtedly, Debnath and

Kelbaugh are correct about better management and higher density housing being a

means of mitigating the impact of climate change, but the COVID-19 pandemic has

demonstrated the adage that where it comes to environmental problems “there’s

no such thing as a free lunch” and the solution to one problem frequently leads

to the creation of other unanticipated consequences.

Migration

is also a major theme of Travis Edwards and Luis Gautier’s article for this

issue of the JP&S which examines the relationship between carbon dioxide

emissions and population. Where previous studies have concentrated on per

capita carbon dioxide emissions, Edwards and Gautier are concerned with how

increases in population and the use of alternative energy sources affect total

emissions in the USA where immigration is the main driver of population growth.

Edwards and Gautier propose a new model where the Demographic Transition Model

(DTM) (the idea that as countries develop population growth rises and then

falls), and IPAT[3] are

integrated into the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) (the inverted U shaped

graph that frequently shows that as wealth increases pollution at first rises

and then falls). They argue that the concentration on per capita emissions in

most of the EKC literature fails to acknowledge population growth can lead to

increases in total emissions even when per capita emissions are falling. As a

major contributor to the reduction in per capita carbon emissions, Edwards and

Gautier go on to estimate a threshold of alternative energy generation after

which total emissions may fall. Furthermore, following their proposed

DTM-IPAT-EKC model, they argue that the shift in lifestyle that immigrants

experience as they move from low/medium income countries into high-income countries

may contribute to total emissions growth, however this will depend on the level

of alternative energy present in the destination country. They suggest that at

present the rate of growth of alternative energy generation in the US is

insufficient to offset population growth.

Edwards

and Gautier note that, since their study considered total carbon dioxide

emissions rather than consumption-based emissions, future research should

address this. This would raise some interesting questions since research examining

the effect of immigration on CO2 emissions

tends, not unreasonably, to assume that with rising income migrant consumption

conforms to the higher levels of the destination country (see for example Weber

and Sciubba 2018; Cafaro and Götmark 2019). However, this assumption is open to

question since it is well established that remittances from migrants to their

country of origin represent around three times the value of official

development aid (Ratha et al. 2016) and migrant saving levels are also significant

(De et al. 2014). Such income use will have an obvious impact on immigrant

consumption levels, but also shifts our understanding of migration towards a

global developmental perspective. Remittances represent a significant

contribution to development which can have environmentally beneficial effects

(Hecht et al. 2006; Jaquet et al. 2016; Oldekop et al. 2018; but see also Davis

and Lopez-Carr for a more ambiguous account) and under some circumstances lead

to lower fertility (Anwar and Mugha 2016; Green et al. 2019; Paul et al. 2019.

See also Ifelunini et al. 2018 for an account of increased fertility with

remittance receipt). While the impact of remittances on both environmental

impact and fertility is complex and uneven it would appear that the evidence

supports a potentially positive impact if other structures (education systems

and sexual health services for example) are present. Again, the consequences of

the COVID-19 pandemic are pertinent here. As a consequence of the lockdown and

probable economic recession in rich countries, remittances to the low and

middle-income countries are likely to fall as migrants lose their jobs. The

World Bank (2020) estimates that remittance flows to low and middle-income

countries are likely to fall by around 20% at a time when need will be greatest

and foreign direct investment is likely to fall by around 35%. The longer-term

impact on both human wellbeing, population growth and environmental impact will

depend on the actions of countries in the Global North. The impact of COVID-19

came after the submission of Edwards and Gautier’s paper, but their conclusion

is prescient:

The

ability to collectively lower our environmental impact in both advanced and

developing economies is vital to the future of the planet. Implementing

effective environmental and economic policies which can be strategically

enacted for specific stages of development, to reduce overall environmental

degradation while maintaining an acceptable standard of living, is crucial to

this task.

In

the post-pandemic world attention to the welfare of people in developing

countries is in the interest of us all.

Notes

[1] As per Holdren and Ehrlich’s (1971)

impact = population x affluence x technology (IPAT)

[2] Dufy et al. do not connect poverty with

population growth, however it is nonetheless a crucial dimension (UNFPA 2014)

[3] See note 2.

References

Anwar

A.I., Mughal, M.Y., 2016. Migrant remittances and fertility. Applied Economics. DOI:

10.1080/00036846.2016.1139676

Cafaro,

P., Gotmark, G., 2019. The potential environmental impacts of EU immigration

policy: future population numbers, greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity

preservation. The Journal of Population and Sustainability. 4(1), pp.71-101.

Carr, D. 2009. Population and

Deforestation: why rural migration matters. Progress in Human Geography,

33(3), pp.355-378.

Cohen,

J.E., 2010. Population and climate change. Proceedings of the American

Philosophical Society. 154(2), pp.158-182

Cohen,

J.E., 2017. How many people can the Earth support? The Journal of Population and Sustainability. 2(1), pp.37-42.

Dasgupta,

A., Dasgupta, P., 2017. Socially embedded preferences, environmental

externalities, and reproductive rights. Population and Development

Review 43(3),

pp.405–441.

Davis,

J., Lopez-Carr, D., 2010. The effects of migrant remittances on population–

environment dynamics in migrant origin areas: international migration,

fertility, and consumption in highland Guatemala. Population and Environment. 32, pp.216–237. DOI:10.1007/s11111-010-0128-7

De,

S., Ratha, D., Yousefi, S.R., 2014. A note on international

migrants’ savings and incomes. [pdf]

Washington D.C.: World Bank. Available at:

https://blogs.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/Note%20on%20Diaspora%20Savings%20Sep%2023%202014%20Final.pdf

[Accessed 15 June 2020].

Duffy,

R., St John, F.A.V., Büscher, B., Brockington, D., 2016. Toward a new

understanding of the links between poverty and illegal wildlife hunting. Conservation Biology. 90(1), pp.14-22. DOI: 10.1111/cobi.12622

Ehrlich,

P.R., Holdren, J.P., 1971. Impact of population growth. Science, New Series. 171(3977), pp.1212-17.

Green,

S.H., Wang, C., Ballakrishnen, S.S., Brueckner, H., Bearmand, P., 2019.

Patterned remittances enhance women’s health-related autonomy. SSM Population Health. 9, 100370.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100370

Hecht,

S.B. Kandel, S., Gomes, I., Cuellar, N., Rosa, H., 2006. Globalization, forest

resurgence, and environmental politics in El Salvador. World Development. 34(2), pp.308–323.

doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.09.005

Ifelunini,

I.A., Ugwu, S.C., Ichoku, H.E., Omeje, A.N., Ihim, E., 2018. Determinants of

fertility rate among women in Ghana and Nigeria: implications for population

growth and sustainable development. African Population Studies. 32(2)(S.2).

ILO,

2020. ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and

the world of work. Third edition. [pdf]

Geneva: International Labour Organization. Available at:

https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_743146.pdf

[Accessed 4 May 2020]

IOM

2020. World migration report 2020.

[pdf] Geneva: International Organization for Migration. Available at:

https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf [Accessed 11 June

2020].

Jaquet,

S., Shrestha, G., Kohler, T., Schwilch, G., 2016. The effects of migration on

livelihoods, land management, and vulnerability to natural disasters in the

Harpan Watershed in Western Nepal. Mountain Research and

Development, 36(4) pp.494-505 https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-16-00034.1

Jin

J.M., Bai P., He W., Wu F., Liu X.F., Han D.M., Liu S., Yang J.K., 2020. Gender

differences in patients with COVID-19: focus on severity and mortality. Frontiers in Public Health Vol. 8 Article 152.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152

Kong,

R., Diepart, J., Castella, J., Lestrelin, G., Tivet, F., Belmain, E., Bégué,

A., 2019. Understanding the drivers of deforestation and agricultural

transformations in the Northwestern uplands of Cambodia. Applied Geography, 102(1), pp.84-98.

Lopez-Carr,

D., Burgdorfer, J., 2013. Deforestation drivers: Population, migration, and

tropical land use. Environment,

55(1) pp.3-11.

Nijman,

V., 2010. An overview of international wildlife trade from Southeast Asia. Biodiversity and Conservation, 19, pp.1101–1114.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-009-9758-4

Oldekop,

J.A., Sims, K.R.E., Whittingham, M.J., Agrawala, A., 2018. An upside to

globalization: international outmigration drives reforestation in Nepal. Global Environmental Change, 52 pp.66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.06.004

Paul,

F.H., Talpur, G.H., Soomro, R., Marri, A.A., 2019. The impact of remittances on

fertility rate: evidence from Pakistan. Sindh University Research

Journal (Science Series). 51(01), pp.129-134. http://doi.org/10.26692/sujo/2019.01.23

Ratha,

D., De, S., Plaza, S. Schuettler, K., Shaw, W., Wyss, H., Yi, S. 2016. Migration and Remittances – Recent Developments and Outlook.

Migration and Development Brief 26, April 2016, Washington, DC: World Bank.

DOI: 10.1596/ 978-1-4648-0913-2

Rosen,

G.E., Smith, K.F., 2010. Summarizing the Evidence on the International Trade in

Illegal Wildlife. EcoHealth 7, pp.24–32.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-010-0317-y

Ryerson,

W. N., 2018. The hidden gem of the Cairo consensus: helping to end population

growth with entertainment media. The Journal of Population and

Sustainability. 2(2), pp. 51–61.

UN,

2018. 68% of the world population

projected to live in urban areas by 2050, says UN. [online] New York: United Nations.

Available at:

https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html

[Accessed 13 June 2020].

UN,

2020. Policy brief: the impact of

COVID-19 on women. [pdf]

New York: United Nations. Available at:

https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/report/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women-en-1.pdf

[Accessed 13 June 2020]/

UNFPA

(United Nations Population Fund), 2014. Population and poverty.[online]

New York: UNFPA. Available at:

https://www.unfpa.org/resources/population-and-poverty [Accessed 12 June 2020]

Weber,

H., Sciubba, J.D., 2018. The effect of population growth on the environment:

evidence from European regions. European Journal of Population, [e-journal] April 9, 2018.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-018-9486-0

Wolfe,

N. D., Daszak, P., Kilpatrick, A. M., & Burke, D. S., 2005. Bushmeat

hunting, deforestation, and prediction of zoonoses emergence. Emerging infectious diseases, 11(12), pp.1822–1827. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1112.040789

Wong,

G., Bi, Y-H., Wang, Q-H., Chen, X-W., Zhang, Z-G., Yao, Y-G., 2020. Zoonotic

origins of human coronavirus 2019 (HCoV-19 / SARS-CoV-2): why is this work

important? Zoological Research.

doi: 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2020.031

World

Bank, 2020. COVID-19 crisis through a

migration lens. Migration and development brief 32. [pdf] Washington D.C.: World Bank Group.

Available at:

http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/989721587512418006/pdf/COVID-19-Crisis-Through-a-Migration-Lens.pdf

[Accessed 2 June 2020]

Ye,

Z. W., Yuan, S., Yuen, K. S., Fung, S. Y., Chan, C. P., Jin, D. Y., 2020. Zoonotic

origins of human coronaviruses. International journal of

biological sciences, 16(10),

1686–1697. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.45472