Achieving a post-growth green economy

First online: 25 November 2020

Douglas

E. Booth

Associate

Professor Retired, Marquette University

cominggoodboom@gmail.com

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

DOI: 10.3197/jps.2020.5.1.57

Licensing: This article is Open Access (CC BY 4.0).

How to Cite:

Booth, D.E. 2016. 'Achieving a post-growth green economy'. The Journal of Population and Sustainability 5(1): 57–75.

https://doi.org/10.3197/jps.2020.5.1.57

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Abstract

A transformation in human

values in a ‘post-materialist’ direction by middle-class youth around the world

may be setting the stage for a new reality of near-zero economic growth and a

sustainable and healthy global biosphere. Evidence from the World Values Survey

suggests that a global expansion of post-material values and experiences leads

to (1) a reduction in consumption-oriented activities, (2) a shift to more

environmentally friendly forms of life that include living at higher, more

energy efficient urban densities, and (3) active political support for

environmental improvement. Such behavioral shifts provide a foundation for a

turn to a slow-growth or even no-growth economy in comparatively affluent

countries to the benefit of a healthier global biosphere. To set the stage for

a ‘post-growth green economy’ that features climate stability and a

substantially reduced ecological footprint, the timing is right for a ‘Green

New Deal’ that focuses on de-carbonizing the global economy and has the

side-benefit of fostering an economic recovery from the Covid-19 global

recession currently underway. The financing of global decarbonization by the

world’s wealthiest countries is affordable and could stimulate much needed

economic improvements in developing countries by creating within them modern,

efficient clean energy systems that can serve as a basis for increased economic

prosperity. Such prosperity will in turn accelerate declines in population

fertility and result ultimately in reduced global population growth.

Keywords: post-materialism; post-growth economy;

green economy; population growth; sustainability.

Introduction

In

this day and age of existential threats to global social and economic

tranquility from the likes of climate change, rising economic inequality,

emerging authoritarian populism, and, now, a Covid-19 pandemic, to think about

prospects for the future may seem naïve. But the future will come and hope

springs eternal. Potentially, Covid-19 will teach us that global problems,

climate change in particular, cannot be ignored and that new approaches are

needed to arrive at a more just and environmentally friendly world. The purpose

of this article will be to suggest a possible path forward by thinking

seriously about interconnections between two phenomena: the ‘post-material

silent revolution’ as a key historical event; and a ‘post-growth green economy’

as a solution to the global environmental crisis. The central thesis offered

here is that these phenomena blend together comfortably as a framework for

thinking about our economic and environmental future.

The

‘post-material silent revolution’ amounts to a sea-change in values among

middle-class youth around the world away from giving high social priorities to

materialist, economic social goals and towards non-economic social purposes

such as advancing freedom of expression and increasing social tolerance. This

change is accompanied by less emphasis on the pursuit of wealth and material

possessions and more emphasis on seeking cultural and social experiences that

take place outside the sphere of economic transactions or within the economic

arena but for non-economic purposes. We will see that such a shift in outlook

and activity brings forth a less entropic and more environmentally friendly way

of living and greater political support for sustaining a healthy natural

environment that together may well lead to big changes in the way we think

about the economy.

A

‘post-growth economy’ refers here to the empirical phenomena of affluent

economies experiencing a slowing of growth in both per-capita incomes and

population as they mature and attain a threshold of material affluence.

Post-growth is achieved when those economies attain a no-growth status, or even

slow decline. Japan in recent years comes close to this status with a 0.8%

annual growth in GDP per capita (2000-2018) and 0.0% annual population growth

(World Bank, 2019c, 2019e).

Worried

about serious degradation of the earth’s natural environment by an

ever-expanding global economy, ecological economists have begun to consider the

somewhat heretical idea of a ‘post-growth economy’ as essential for halting the

over-exploitation of the biosphere caused by the excessive extraction of energy

and material resources, damaging emissions of waste materials and gases, and

the degrading and destruction of natural habitats. The post-growth idea is

heretical simply because continuous global economic growth is taken as a given

in the modern corporate-capitalist reality and as a fundamental requirement for

bringing the good life to all the peoples of the world. The necessity of

economic growth for living well and the compatibility of growth with a

sustainable global biosphere has been challenged by a number of authors,

challenges nicely summarized a few years ago in Peter Victor’s, Managing Without Growth and more recently by Tim Jackson’s Prosperity Without Growth (Jackson, 2017; Victor, 2008

pp.170-174). Simply put, no growth in the world’s highly developed countries is

essential to halting dangerous degradations of the earth’s environment, and a

post-growth economy is perfectly compatible with a decent life once a certain

threshold of prosperity is achieved. Other than for committed

environmentalists, a post-growth economy never has had a substantial political

constituency in the past, but with the emergence of increasing numbers of

post-materialists around the world, the absence of such a constituency is no

longer the case. Post-materialism provides a real-world value-foundation and

form of life for a materially and environmentally stable, ‘post-growth green

economy’. This

is the key proposition to be explored in the pages to follow.

The post-material silent

revolution

The

future spreading of a post-material silent revolution around the world, I will

now argue, provides an economic and political foundation for a post-growth

green economy, an outcome that may well be essential to prevent the existential

threat of climate change to the global biosphere (more on this in the next

section). The silent revolution will assist in bringing about such an economy

for the following reasons: (1) first and foremost, post-materialists likely

consume relatively less over their life-time than materialists with similar

economic opportunities; (2) post-material forms of living and experiences tend

to be less entropic than materialist ways of life; and most important of all

(3) post-materialists are more supportive of environmental protection than

others in both their attitudes and political actions.

Post-materialists

are individuals whose quest in life has shifted away from the acquisition of

material possessions and towards the pursuit social goals and experiences

valued for their own sake largely outside the realm of market transactions

(Booth, 2018a). This quest is enabled by having grown up in social environments

of reasonable physical and material security that permit a lifetime focus on

higher ordered purposes at the upper reaches of the hierarchy of human needs

(Inglehart, 1971; Maslow, 1987). Such individuals are less interested than

others in gaining riches and material possessions and achieving publicly

recognized personal success according to analyses of World Values Survey, Wave

6 (2010-2014) data covering 60 countries and more than 85,000 respondents

worldwide (Booth, 2018a; World Values Survey Association, 2015).

Post-materialists also possess a universalist outlook meaning they desire to

take positive actions to the benefit of society as a whole and for the

protection of nature and the earth’s environment. Adding this all up infers

that post-materialists are prone to consume less in the way of material

possessions over their lifetime than others with similar economic

opportunities. Thus, the silent revolution in post-material values likely

serves to dampen life-time consumption and the material throughput that goes

with it.

Having

attained a basic threshold of economic security and material possessions,

post-materialists not only limit their overall demand for material goods, but

as a matter of taste seek a comparatively low-entropy, form of life placing

less demand on energy and materials flows to the benefit of the environment.

Post-materialists are more inclined than others to reside in larger, denser

cities that are more energy efficient and thus less entropic than the

spread-out suburban areas so attractive to their older peers after World War II

(Booth, 2018b). Energy efficiency increases with human density for such reasons

as reduced human travel distances; less use of energy inefficient private motor

vehicles and more use of energy efficient public transit; and lower per person

consumption of private dwelling space and associated heating and cooling energy

requirements (New York City, 2007; Newman & Kenworthy, 1999, 2015).

In the USA a return to downtown living has been driven in part by Millennials

choosing to live in high-density urban neighborhoods as opposed to spread out

low-density suburbs (Birch, 2005, 2009). Even in already densely populated

countries such as Germany, center-city, dense neighborhoods recently

experienced a relative surge in population growth driven by younger generations

(Brombach, Jessen, Siedentop, & Zakrzewski, 2017). Complementary to

higher-density living by younger generations in the USA, the rate of car

ownership and the miles of driving undertaken by Millennials is less than their

older peers (Polzin, Chu, & Godrey, 2014). Higher urban densities support

more of the publicly shared experience opportunities afforded by parks,

libraries, public squares, museums, art galleries, entertainment and sports

venues, spaces for group meetings and public demonstrations, street cafes, and

more that provide opportunities for a post-material mode of living (Markusen,

2006; Markusen & Gadwa, 2010; Markusen & Schrock, 2006).

In

addition to being oriented to a less entropic form of life, post-materialists

exhibit greater support for the environment than others in terms of both their

attitudes and actions in the world (Booth, 2017; Inglehart, 1995). This support

is not just a matter of personal preferences but includes such overt actions as

contributing to environmental groups, attending environmental protests, and in

Europe giving support to the Green Party movement.

To

summarize, the long-term trend to post-materialism around the world fueled by

generational replacement is a good thing for the global biosphere by fostering

more energy efficient, less entropic forms of living, taking the pressure off

of growing demand for material possessions that threatens the global biosphere,

and increasing active political support for protecting the global

biosphere. This trend lends support to the emergence of a ‘post-growth

green economy’ as a foundation for stabilizing the global climate in particular

and increasing the health of the biosphere in general.

The post-growth green economy

The

concept of a post-growth green economy is inspired by the recognition that a

global economic system functioning within a fixed biosphere cannot expand

forever without doing substantial harm to the latter (Daly, 1991, 2018). The

biosphere receives energy but only miniscule amounts of materials from the

solar system of which it is a part. The economic system is totally

dependent on the biosphere for both energy and matter. The laws of

thermodynamics tell us that, while neither energy nor matter can be destroyed,

their quality declines with human use. The economic system extracts high

quality energy and materials from the biosphere and returns waste heat and

low-quality waste materials back to it. The supply of energy and matter is

ultimately limited as is the capacity of the biosphere to absorb resulting

wastes without undue harm to biotic functioning. Accounting for this

limitation, a post-growth green economy is founded on the principle that energy

and materials flows in particular, and the environmental scale of the economy

in general, should be capped at sustainable amounts consistent with an

ecologically healthy biosphere (Booth, 1998).

Paradoxically,

the problem with a post-growth green economy is not so much attaining zero

growth but realizing a green economy such that energy and material flows and

waste emissions are capped at sustainable levels consistent with the

maintenance of global ecosystem health. The next section will focus on bringing

waste emissions down to environmentally sustainable levels within the context

of a post-growth economy, and the current section will address the seeming

inevitability of realizing a post-growth economy.

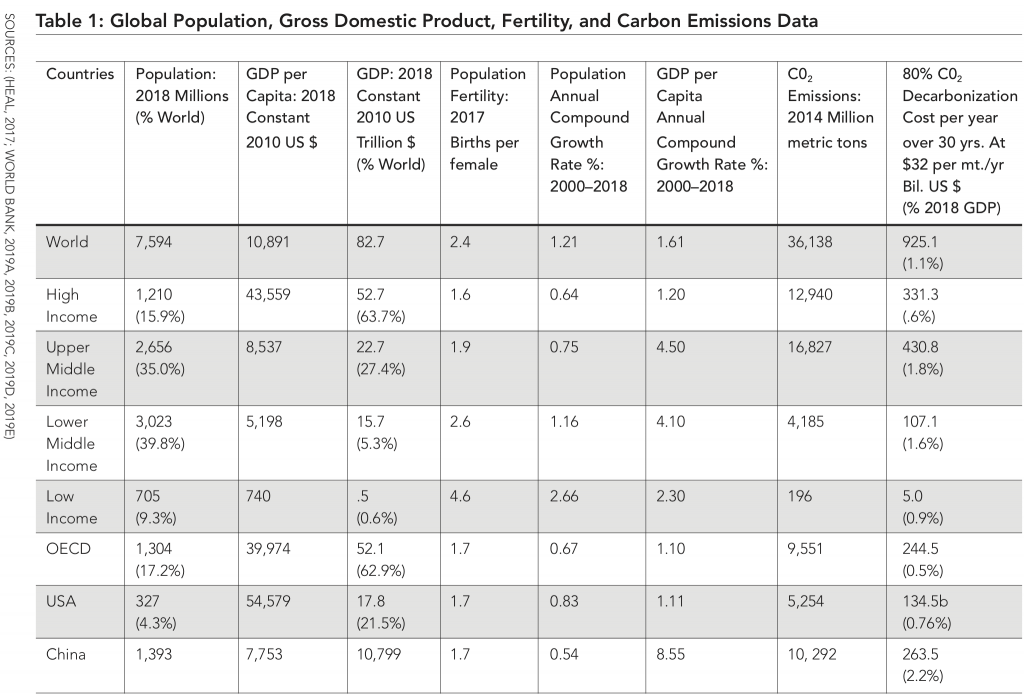

For

those countries at the upper-end of the human development hierarchy, the notion

of a zero-growth economy is quickly coming to fruition. If we look at the

world’s high-income countries, their population fertility rate has already

reached 1.6 children per female and their annual population growth rate is down

to 0.64% per year and will eventually turn negative (Table 1). For the most

affluent countries of the world, zero population growth or even population

decline will be a fact of life in the not too distant future assuming an

absence of a significant upsurge in immigration. Moreover, for this same group

of countries, real GDP growth per capita is slowing as well and is down to 1.2%

a year between 2000 and 2018 from 2.4% between 1980 and 2000, a 50% drop (World

Bank, 2019c). With zero or even negative population growth and with the GDP

annual growth rate per capita closing in on 1% or less, a no-growth economy

looks to be on the way for the world’s most affluent countries.

This

prospect leaves us with important unresolved questions: Why are the wealthiest

economies in the world tending towards zero economic growth? Is this a problem

for human well-being in wealthy countries? In a world where many countries need

human development and expansion of their economies to achieve a minimum

threshold income necessary for the good life, is there a path to forestalling

excessive climate change by mid-century and ultimately attaining sufficient

economic security for all the world’s citizens that would enable a global

post-growth green economy?

Growth

in constant dollars GDP divides into two factors: (1) growth in population, and

(2) growth in real GDP per capita. Growth in population ultimately depends on

the fertility rate, the number of births per female, of which the population

replacement level is approximately 2.1. Over the long-run, fertility rates

above this number result in population growth and below it in population

shrinkage. Fertility rates appear to be heavily dependent on the level of human

and economic development. Basically, as material affluence increases, fertility

diminishes as shown in the data in Table 1. Approximately half the world’s

population (High Income plus Upper Middle Income, Table 1) now possesses a

fertility rate below replacement levels at approximately 1.81 and the other

half (Lower Middle Income plus Low Income, Table 1) has a fertility of approximately

3.0. With global fertility at 2.4, long-run population stability is within

reach. By roughly doubling the GDP per capita for the lower half of the world’s

population, their fertility rate can probably be driven below 2.1. Doing so

would result in an average GDP per capita for the lower half at least equal to

the GDP per capita of the upper-middle income ($8,537) countries who currently

possess a fertility rate of 1.9, which is below the population replacement

level (Table 1). At the current GDP per capita growth rate for the lower half,

a more than doubling of GDP per capita will occur in less than 30 years.

As

shown by Table 1 data, in both high-income and OECD countries, GDP per capita

is growing at a historically modest rate just above 1% annually. Such growth

theoretically occurs from a combination of increases in the number of hours

worked per capita and in output per hour worked (constant $ GDP/hours worked).

Between 2000 and 2018, OECD hours worked per capita remained unchanged, while

output per hour (labor productivity) has grown 1.2% annually (OECD, 2019a,

2019b, 2019c). Growth in GDP per capita is consequently due entirely to

productivity growth, but at a rate that over the long run has been in decline

for wealthy countries. As Tim Jackson notes, labor productivity in the world’s

most advanced economies has fallen steadily from a high in the 4% range just

after World War II to around 2% in the 1980s and 1990s, and now to less than 1%

since the turn of the century. As he also notes, the reasons for this are a

matter of some contention and include a slowing in the pace of technological

innovation placing a drag on the supply side of the economy and stagnant growth

on the demand side of the economy dampening productivity improving investment

in new production facilities (Jackson, 2017 pp. 43-46). Slower growth on the

demand side of the economy is driven in part by growing economic inequality, a

lack of real wage growth, and the disruptions of the 2008-2009 Great

Recession (Alvaredo, Chancel, Piketty, Saez, & Zucman, 2017; Saez, 2009;

Stiglitz, 2010; Wisman, 2013). A shift in the structure of modern

post-industrial economy in the direction of services and away from goods can

make a difference as well. Face-to-face human services intrinsically lack

opportunities for labor productivity improvements, meaning that overall

productivity growth is likely to shrink as the service sector expands

relatively (Jackson, 2017, 170-174). In addition, since many service jobs are

low-paying, a relative expansion of services can place a drag on earnings at

the lower end of the social class structure (Storm, 2017) adding to economic

inequality. These reasons for slower growth in productivity imply that modern

capitalism possesses critical inner flaws that taken together will ultimately

bring economic growth as we know it to an end.

A

slowing of growth in the world’s most affluent economies could also be occurring

for positive reasons below the radar as a matter of public choice, and not

entirely as the result of dis-functional economic arrangements. The

post-material silent revolution described above amounts to a turning away from

the pursuit of more material possessions to other purposes once a threshold of

material security is achieved. For the total World Values Survey, Wave 6

sample, 31% of the respondents selected a majority of post-material social

options for the questions behind the construction of the Inglehart

post-materialism index instead of economically focused materialist options

(Booth, 2018a; World Values Survey Association, 2015). This number rises to

39.8% for affluent countries in the top 25% of the human development hierarchy

as measured by the Human Development Index (United Nations Human Development

Program, 2018). A substantial proportion of the population in wealthy countries

subscribes to post-materialist social goals, and many of those same individuals

participate in post-materialist experiences outside the arena of market

transactions. Engaging in such experiences likely dampens consumer spending and

could well lead to a slowdown in aggregate demand growth and in economic

expansion. The point is a simple one; achieving a decent and satisfying life is

contingent on a minimum threshold of material wealth but ‘not’ on continuous

economic growth once that minimum is achieved.

This

is exactly the same point made by both Jackson and Victor in their separate

works on no-growth economics (Jackson, 2017; Victor, 2008). Both note that

neither happiness nor genuine social progress necessarily occurs as a

consequence of GDP growth. Happiness does increase with income up to a certain

minimum, but after that the rate of increase flattens out. A minimum

country-level GDP per capita threshold is required to achieve relatively high

life expectancy and a decent education, both essential to

life-satisfaction. Beyond this threshold, post-materialists shift gears

towards supporting non-economic social goals such as freedom of

self-expression, having more say in all of life’s arenas, and supporting a more

humane society based on ideas rather than money. Post-materialism around the

world bears a strong positive correlation to such basic values as being creative

and doing something for the good of society and the environment (Booth, 2018a).

Those who engage in post-materialist experiences desire connections with others

in voluntary organizations, creative and independent activity in their work,

and active political participation in the pursuit of valued social goals. These

are ‘intrinsic’ purposes, as opposed to materialist ‘extrinsic’ ends sought in

market transactions, and bear a strong relationship to the intrinsic values

of “self-acceptance, affiliation, and a sense of belonging in the

community” mentioned by Jackson as important for flourishing in a prosperous

world where economic growth ceases to be a fundamental social premise (Jackson,

2017). In support of a basic human desire for realizing intrinsic values,

Jackson points to a ‘quiet revolution’ of people accepting lower incomes to

leave room in life for the simple pleasures (reading, gardening, walking,

listening to music), getting involved in the voluntary simplicity movement,

or taking part in creative and engaging activities characterized by a sense of

flow (a state of heightened focus). These are exactly the kinds purposes sought

by those possessing post-material values and engaging in post-material

experiences, phenomena that find substantial empirical support in the World

Values Survey (Booth, 2018a, 2018b).

To

sum up, the world’s richest countries are tending towards annual rates of

economic expansion in per capita income below 1% and annual rates of population

growth likely to fall below zero in the not too distant future absent

significant immigration. Potential explanations for the decline in per capita

income growth include a mix of structural problems on both the demand and

supply side of the economy. Alternatively, the decline may not be a problem at

all but simply reflect a movement by a portion of the population beyond

extrinsic materialist pursuits in life to more satisfying post-materialist

intrinsic purposes. Future population declines follow from fertility

rates below replacement levels that have in turn resulted from relatively high

rates of affluence and human development.

Climate change and achieving a

green global economy

An

essential environmental virtue of a post-growth economic system is the stabilizing

of the extraction of energy and materials from, and waste emissions into, the

global biosphere. A post-growth economic system has other environmental

benefits as well including limitations on the human damage to ecosystem

functioning required for both human and nonhuman species survival. Such

stability in energy and materials throughputs and ecological harms doesn’t

necessarily mean a healthy and sustainable biosphere since existing (stable)

rates of human environmental intrusions may well lead to continuing ecological

degradation. In other words, certain human-caused environmental harms will have

to be reduced below existing levels for a healthy and sustainable biosphere in

a post-growth economy. A simple steady state in the human use of the environment

will not be enough. The Global Footprint Network, for example, reports

that the worldwide ecological footprint in terms of hectares of land needed to

supply the world with the 2016 volume of ecological resources consumed on a

sustainable basis is approximately 1.7 times the amount of land available

globally. In brief, this rate of consumption is above the sustainable level,

and the earth’s resources will continue to degrade under steady-state

consumption at the 2016 rate (Global Footprint Network, 2020). For future

reference, note that if the global economy were 80% decarbonized as will be

describe below, then worldwide ecological footprint would decline to

approximately 0.9 times the amount of land available based on the 2016 numbers.

Decarbonization would in effect eliminate the huge land requirements for carbon

absorption and bring the ecological footprint into sustainability.

The

most threatening of all human induced environmental harms clearly is the

unsustainability of waste greenhouse gases being emitted into the global

atmosphere. Even in a global no-growth economy, such emissions would continue

at climate threatening rates, although these would slowly diminish over time

because of improvements in energy efficiency and resulting reductions in CO2 emissions

per unit of global GDP (currently approximately 0.6% per year) (Jackson, 2017

p.97). Currently, worldwide CO2 emissions stand at around 36 billion

metric tons annually (Table 1). To drive these emissions down by 80% at

mid-century over a thirty-year period would require an annual rate of decline

of approximately 5.2%. Without any concerted action to cut emissions further, no-growth

global economy emissions would only decline by about 20% over 30 years to 29

billion at a 0.6% annual rate. In brief, a no-growth economy globally would not

be enough to come anywhere near de-carbonizing the economic system as a whole.

A global no-growth economy would be a help, but it is not the final solution to

the existential threat of a warming global climate. In a no growth economy, a

4.6% (5.2 -0.6) annual reduction in emissions will be needed for 80%

decarbonization in 30 years. This is indeed less than required in a

‘normal-growth’ global economy with GDP per capita projected to expand over the

next 30 years at a rate of around 1.3% per year and population projected to

grow at 0.8% per year (Jackson, 2017, p. 97). In this case the annual percent

decline in emissions would need to be 6.7% per year (5.2-0.6+1.3+0.8) to

achieve 80% decarbonization.

While

there is nothing new or unfamiliar in the Table 1 statistics, a number of

interesting messages can be gleaned from them. First, as just noted, if current

trends continue the world’s high-income countries are on track to be ‘no-growth

economies’ with GDP per capita income growth trending towards zero and

population growth moving into negative territory. Second, population fertility

remains above the magic 2.1 stabilization rate for roughly the poorest half of

the world’s countries, and an annual GDP per capita above $8,500 apparently

results in fertility dropping below this number. Simply put, per capita income

growth of 2% per year or more over the next 30 years for the poorest half of

the world’s population appears to be a feasible route to bringing fertility

down to population stabilizing levels. Because of the age structure of

populations in low income countries, actually reaching population stability

will take time and could be accelerated with a greater current commitment to

family planning efforts (Sachs, 2008). Growth in per capita income for the

poorest half would also be a help in getting to a basic economic security

threshold capable of bringing on a shift to the pursuit of post-material values

and experiences as opposed to further acquisitions of material possessions.

Third, an 80% decarbonization of the global economy in the next 30 years

appears to be a relative bargain, costing a bit more than 1% of global GDP per

year. Setting China aside as capable of paying its own way, high-income

countries could finance 80% decarbonization for the entire world (excluding

China) at a cost of roughly 1.3% of their GDP per year for 30 years.[1]

The

term ‘Green New Deal’ originated in the UK with a proposal to tackle the 2008

‘Great Recession’ with a large-scale program of public investments and economic

reforms to expand employment, reduce economic inequality, and to create a clean

energy sector for the purpose of bringing climate change to heel (Green New

Deal Group, 2008). More recently, in reaction to the Trump administration’s

attack on USA environmental regulations and with the return of the Democratic

Party to power in the House of Representatives in 2018, a Green New Deal

resolution with similar purposes passed the House (U.S. House of

Representatives, 2019). While the global economic future after the Covid-19

pandemic at this point is murky, the global economy will most likely enter an

economic recession or even a depression with a dramatic decline in economic

activity as a result of business shutdowns to bring spreading of the virus

under control. To foster an economic recovery will surly require an

unprecedented global economic stimulus of which investment in clean energy and

other forms of decarbonization could be quite popular given that a second

crisis in the form of climate change and its devastating consequences will be

staring at everyone on the horizon. The beauty of a Green New Deal is its

probable high degree of political acceptability. It gives environmentalists and

post-materialists a project around which they can coalesce and gain political

momentum; it will create large numbers of well-paying working-class jobs and

potentially bring working-class disaffected populists on board weaning them

away from a currently emergent anti-environment authoritarian populism (Norris

& Inglehart, 2019) in the process; and, last but not least, such a project

could bring the majority of global business interests (fossil fuels excepted)

on board by causing the global economy to flourish with a boom that creates a

new clean energy sector and brings about economic recovery. The process of

replacing fossil fuel with clean energy will create jobs on two counts: First,

clean energy alternatives such as solar and wind will be more labor intensive

than the fossil fuels they are replacing, meaning that employment in the energy

sector will permanently increase as a result of the shift; and secondly, the

initial investment in clean energy facilities will mean a temporary boom in

employment and a surge in economic growth lasting over the transition period

(Garrett-Peltier, 2017; Wei, Patadia, & Kammen, 2010).

My

primary purpose here is to comment on the possible role of a Green New Deal in

setting the stage for a stable and healthy global biosphere. Others have done a

good job in describing how Green New Deal decarbonization can be implemented

(Heal, 2017; Sachs, 2019). First and foremost, a global decarbonization project

could set us on track for climate stabilization at an affordable cost, one that

could easily be fully borne by the world’s high-income countries, setting them

back about 1.3% of their annual GDP as noted above. The financing of a global

Green New Deal by high-income countries would have to be coordinated globally,

perhaps through the Green Climate Fund established by the Paris Climate Accord

(Green Climate Fund, 2019). An obvious virtue of such an approach to financing

would be to foster greater economic equity at a global level between rich and

poor as well as gaining support for decarbonization from all low and

middle-income countries.

Second,

in a Covid-19 economic recovery, debt-financed expenditures on decarbonization

will help high income countries get back to their original levels of economic

activity and also foster economic expansion in the world’s middle and

low-income economies.[2] The

recovery of high-income economies will be advanced by producing much of the

world’s clean energy equipment, and the middle and low-income economies will be

boosted by not only the work of installing such equipment, but by the creation

of a modern energy sector that for many countries did not previously exist and

can serve as a point of departure for other development projects. For the

world’s developing countries, decarbonization and a global Green New Deal can

help push per capita GDP towards thresholds necessary to bring about zero

population growth and provide enough economic security to make a ‘post-material

silent revolution’ globally feasible.

Conclusion

The

essential hypothesis here is this: The ‘post-material silent revolution’,

enabled by the attainment of a critical level of material and physical security

that permits lives less-focused on further economic achievements, sets the

stage for a ‘post-growth economy’ that ultimately can bring the global economic

system into a sustainable balance with the global biosphere. Currently, this is

just a hypothesis, but one that is consistent with a shift by a significant

share of the global population beyond an emphasis on materialist to

post-materialist values and modes of life. This hypothesis is also consistent

with, but not necessarily the entire cause of, a reduction in economic growth

rates to 1% or less for many of the world’s most affluent economies.

Paradoxically, a Green New Deal is proposed here that will actually stimulate

worldwide economic growth in the short-run and at the same time put humanity on

a path to bring a halt to the existential threat of climate change. Such a

stimulus will help foster recovery of the global economy from the Covid-19

economic downturn and set developing economies on a path to reasonable material

security for all of humanity. More importantly, if 80% global decarbonization

had already occurred, the ecological footprint as measured in 2016 would

actually have been about .9 rather than 1.7 due to the reduction in

requirements for carbon absorption, bringing the footprint into sustainability.

Whatever the level of the ecological footprint turns out to be in 2050, it will

be substantially less than otherwise because of decarbonization. In brief,

short-run green economic growth is needed to set the stage for a green

post-growth economy consistent with a stable and healthy global biosphere. Hope

does spring eternal.

Notes

[1]The

decarbonization cost estimates are based on numbers for the USA in (Heal,

2017). Heal estimates 30-year decarbonization costs to fall in a best-case to

worse-case range from $1.3 trillion to $4 trillion. Using the

worst-worst-case figure this equals about $952 per mt for 4.2 million mt USA

emissions reduction over 30 years, or about $32 per ton annually. These cost

figures are likely to be similar to those faced by other high-income economies.

Costs are likely to be somewhat less for countries with lower wage rates such

as China. China is included in the World Bank, Upper Middle-Income country

category, but that country possesses a sophisticated clean energy equipment

industry already and can likely afford to achieve decarbonization using its own

resources. China is already a major exporter of solar panels and other clean

energy equipment and will thus benefit substantially from a global

decarbonization effort. Looking at the cost estimate as a percentage of the

current year GDP means that the annual cost in absolute terms will increase

annually by the growth rate of GDP more than accounting for GDP related

possible growth in emissions.

[2]To

finance the Green New Deal,

high-income countries would be advised to issue long-term government backed

debt-obligations to avoid the drag on economic recovery that tax-financed

spending would bring. Once recovery has occurred, then debt-obligations could

be slowly retired, perhaps funded by a small ‘automated payment transactions’

tax that would be progressive and at the same time would dampen overall

financial transactions and thus contribute to sustaining a ‘post-growth

economy’ (Feige, 2000). Such a tax would likely have a mild negative effect on

consumer expenditures but could well diminish the volume of financial

transactions significantly, especially those undertaken for speculative

purposes. Since the bulk of payment transactions are undertaken in association

with financial assets disproportionately held by the wealthy, the

redistributive effects of payments transactions tax would probably be

progressive.

References

Alvaredo,

F., Chancel, L., Piketty, T., Saez, E., and Zucman, G. 2017. Global inequality

dynamics: new findings from The World Wealth and Income Database. American Economic Review, 107(5), pp.404-409.

Birch,

E. L., 2005. Who lIves downtown? In A. Berube, B. Katz, and R. E. Lang, eds.

2005. Redefining urban and suburban

America: evidence from Census 2000. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution

Press. pp.29-49.

Birch,

E. L., 2009. Downtown in the “new American city”. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science,

626(1), pp.134-153.

Booth,

D. E. 1998. The environmental consequences

of growth: steady-state economics as an alternative to environmental decline.

London: Routledge.

Booth,

D. E. 2018a. Postmaterial experience economics. Journal of Human Values, 24(2), pp.1-18.

Booth,

D. E. 2018b. Postmaterial experience economics, population, and environmental

sustainability. Journal of Population and

Sustainability, 2(2), pp.33-50.

Brombach,

K., Jessen, J., Siedentop, S., and Zakrzewski, P., 2017. Demographic patterns

of reurbanisation and housing in metropolitan regions in the U.S. and Germany. Comparative Population Studies, 42, pp.281-317.

Daly,

H., 2018. Envisioning a successful steady-state economy. Journal of Population and Sustainability,

3(1), pp.21-33.

Daly,

H. 1991. Steady-state economics 2nd ed. Washington D.C.: Island Press.

Feige,

E. L., 2000. Taxation for the 21st century: The automated payment transaction

(APT) tax. Economic Policy,

15(31), pp.473-511.

Garrett-Peltier,

H., 2017. Green versus brown: comparing the employment impacts of energy

efficiency, renewable energy, and fossil fuels using an input-output model. Economic Modelling, 61, pp.439-447.

Green

Climate Fund, 2019. Achieving the Paris Agreement:

How GCF raises climate ambition and empowers action.

[online] Available at: https://www.greenclimate.fund/document/achieving-paris-agreement-how-gcf-raises-climate-ambition-and-empowers-action#

[Accessed 27 October 2020].

Global

Footprint Network, 2020. Data and methodology: World

ecological footprint by land type. [online] Available at:

https://www.footprintnetwork.org/resources/data/ [Accessed 27 October 2020].

Green

New Deal Group, 2008. A

green new deal. [pdf]

Available at:

https://neweconomics.org/uploads/files/8f737ea195fe56db2f_xbm6ihwb1.pdf

[Accessed 27 October 2020]

Heal,

G., 2017. What would It take to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions 80 percent

by 2050? Review of Environmental

Economics and Policy, 11(2), pp.319-335.

Jackson,

T., 2017. Prosperity without growth:

foundations for the economy of tomorrow 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Markusen,

A., 2006. Urban development and the politics of a creative class: evidence from

a study of artists. Environment and Planning, 38,

pp.1921-1940.

Markusen,

A., and Gadwa, A., 2010. Arts and culture in urban or regional planning: a review

and research agenda. Journal of Planning Education

and Research, 29(3), pp.379-391.

Markusen,

A., and Schrock, G., 2006. The artistic dividend: Urban artistic specialisation

and economic development implications. Urban Studies,

43(10), pp.1661-1686.

New

York City, 2007. Inventory of New York City

greenhouse gas emissions. [pdf] Available at:

http://www.nyc.gov/html/planyc/downloads/pdf/publications/greenhousegas_2007.pdf

[Accessed 27 October 2020].

Newman,

P., and Kenworthy, J. R. 1999. Sustainability and cities:

overcoming automobile dependency. Washington D.C.: Island

Press.

Newman,

P., and Kenworthy, J. R., 2015. The end of automobile

dependence: how cities are moving beyond car-based planning.

Washington D.C.: Island Press.

Norris,

P., and Inglehart, R., 2019. Cultural backlash: Trump,

Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

OECD,

2019a. Hours worked.

[online] Available at: https://data.oecd.org/emp/hours-worked.htm [Accessed 27

October 2020].

OECD,

2019b. Level of GDP per capita and

productivity. [online]

Available at: https://data.oecd.org/lprdty/gdp-per-hour-worked.htm

[Accessed 27 October 2020].

OECD,

2019c. Labour force participation

rate. [online]

Available at: https://data.oecd.org/emp/labour-force-participation-rate.htm

[Accessed 27 October 2020].

Polzin,

S. E., Chu, X., and Godrey, J., 2014. The impact of Millennials’ travel

behavior on future personal vehicle travel. Energy Strategy Reviews, 5, pp.59-65.

Sachs,

J., 2008. Common wealth: economics for a

crowded planet. New

York: Penguin Press.

Sachs,

J., 2019. Getting to a carbon-free

economy. [online]

Available at:

https://prospect.org/greennewdeal/getting-to-a-carbon-free-economy/ [Accessed

27 October 2020].

Saez,

E., 2009. Striking it richer: the evolution of top incomes in the United States

(update with 2007 estimates). UC Berkeley: Institute for

Research on Labor and Employment. [online]

Available at: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8dp1f91x [Accessed November 4, 2020].

Stiglitz,

J. E., 2010. Freefall: America, free

markets, and the sinking of the world economy. New

York: W.W. Norton.

Storm,

S., 2017. The new normal: demand, secular stagnation, and the vanishing middle

class. International Journal of

Political Economy, 46(4), pp.169-210.

U.S.

House of Representatives, 116th Congress, 2019. House Resolution 109. Recognizing the duty of the federal

government to create a green new deal.Washington D.C.: U.S.

Government Printing Office.

Victor,

P. A., 2008. Managing without growth: slower

by design, not disaster. Cheltenham:

Edward Elgar.

Wei,

M., Patadia, S., and Kammen, D. M., 2010. Putting renewables and energy

efficiency to work: how many jobs can the clean energy industry generate in the

U.S.? Energy Policy, 38,

pp.919-931.

Wisman,

J. D., 2013. Wage Stagnation, rising inequality and the Financial Crisis of

2008. Cambridge Journal of Economics,

37(4), pp.921-945.

World

Bank, 2019a. CO2 emissions (kt).

[online] Available at:

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.ATM.CO2E.KT?end=2014&start=1960&view=chart

[Accessed 27 October 2020].

World

Bank, 2019b. Fertility rate, total (births

per woman). [online] Available at:

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN/ [Accessed 27 October

2020].

World

Bank, 2019c. GDP per capita (constant 2010

US$). [online] Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD

[Accessed 27 October 2020].

World

Bank, 2019d. Population growth (annual %).

[online] Available at:

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.GROW?end=2011&start=1961

[Accessed 27 October 2020].

World

Bank, 2019e. Population, total. [online] Available at:

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/sp.pop.totl [Accessed 27 October 2020].