Nudging interventions on sustainable food

consumption: a systematic review

First online: 21 July 2021

Becky

Blackford

Bournemouth University

blackfordbecky@gmail.com

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

DOI: 10.3197/jps.2021.5.2.17

Licensing: This article is Open Access (CC BY 4.0).

How to Cite:

Blackford, B. 2021. 'Nudging interventions on sustainable food consumption: a systematic review'. The Journal of Population and Sustainability 5(2): 17–62.

https://doi.org/10.3197/jps.2021.5.2.17

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Abstract

As population growth continues,

sustainable food behaviour is

essential to help reduce the anthropogenic modification of

natural systems, driven by food production and consumption, resulting in

environmental and health burdens and impacts. Nudging, a behavioural concept,

has potential implications for tackling these issues, encouraging change in

individuals’ intentions and decision-making via indirect proposition and

reinforcement; however, lack of empirical evidence for effectiveness and the

controversial framework for ethical analysis create challenges. This systematic

review evaluated the effectiveness of nudging interventions on sustainable food

choices, searching five databases to identify the effectiveness of such

interventions. Of the 742 identified articles, 14 articles met the eligibility

criteria and were included in this review. Overall, the potential of certain nudging interventions for encouraging

sustainable food choices were found in strategies that targeted ‘system 1’

thinking (automatic, intuitive and non-conscious, relying on heuristics, mental

shortcuts and biases), producing outcomes which were more statistically

significant compared to interventions requiring consumer deliberation. Gender,

sensory influences, and attractiveness of target dishes were highlighted as

pivotal factors in sustainable food choice, hence research that considers these

factors in conjunction with nudging interventions is required.

Keywords:

nudging interventions; sustainable food choice; food security

Introduction

Population

growth, increased per capita global affluence, urbanisation, increased food

productivity and food diversity, decreased seasonal dependence, and food prices

have caused major shifts in global dietary and consumption patterns (Lassalette

et al., 2014; Tillman and Clark, 2014; Davis et al., 2016).

Westernisation of food consumption has occurred in population growth regions

over the last 50 years, increased demand for meat and dairy, empty calories and

total calories has altered the global nature and nutrient transition scale of

food consumption (Kearney, 2010; Tillman and Clark, 2014). The Food and

Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) suggest that food

production will have to increase by 70% to feed an additional 2.3 billion people

by 2050, with the majority of this population growth occurring in developing

countries (FAO et al., 2020).

The

2019/20 annual global production of cereal grains (2.7 billion tonnes) alone is

capable of providing adequate nutritional energy to 10-12 billion people

(Cohen, 2017; FAO et al., 2020). However, issues surrounding the allocation and

utilisation of cereal grains has led to 43% being used for human food

consumption, 36% for animal feed and 21% for other industrial uses such as

biofuels. This utilisation can price the most vulnerable people out of the

world grain market, limiting food choices, purchases, and human wellbeing

(Cohen, 2017). The FAO estimate that 8.9% (690 million) of the global

population are undernourished and 9.7% (750 million) are exposed to severe

levels of food insecurity (FAO et al., 2020).

Global

food production is a significant driver in the anthropogenic modification of

natural systems, causing burdens and impacts on both the environment and human

health. Externalities including environmental impact (e.g., climate change,

biodiversity loss, and natural resource depletion), and negative impacts on

human health and culture (e.g., obesity, cancer, diabetes, loss of cultural

heritage, impacts on rural businesses, access to green spaces) are generally

not included in the price of commodities (Lassalette et al., 2014; Beattie and

McGuire, 2016; Benton, 2016; Notarnicola et al., 2017; Schanes et al., 2018;

Sustainable Food Trust, 2019; Taghikhah et al., 2019; Viegas and Lins, 2019).

Encouraging consumers to adopt more sustainable food behaviour, such as locally

sourced foods or diets containing less meat, is essential to reduce the impact

of food production and consumption, especially in developed countries (Kerr and

Foster, 2011; Schoesler et al., 2014; Hartmann and Siegrist, 2017; Ferrari, et

al., 2019; Hedin et al., 2019; FAO, 2019; de Grave et al., 2020).

Sustainable

consumption (SC) was first highlighted in the 1992 United Nations Conference on

Environment and Development, chapter 4 – Agenda 21 (UNCED, 1992), and

defined in the 1994 Oslo Symposium on Sustainable Consumption as:

the

use of services and related products which respond to basic needs and bring a

better quality of life while minimising the use of natural resources and toxic

materials as well as emissions of waste and pollutants over the life cycle of

the service or product so as not to jeopardise the needs of future generations.

(United Nations, 2020, p.8)

The

2018 Third International Conference of the Sustainable Consumption Research and

Action Initative (SCORAI) in Copenhagen highlighted the role of behavioural

economics and related strategies on consumption routines to assist SC (SCORAI,

2018). Hence it is vital to understand human behaviour as complex and

influenced by cognitive bias and heuristics (Fischer et al., 2012; Lehner et

al., 2016).

Kahneman

(2011) proposed that human thinking is driven by two systems:

- system

1- automatic, intuitive and non-conscious, relying on heuristics, mental

shortcuts and biases

- system

2-intervening, deliberate and conscious, relying on the availability of

information and cognitive capacity to process information to make rational

choices

Both

are susceptible to ‘nudges’ that encourage behavioural change within civil

society (Allcott and Mullainathan, 2010; Kahneman, 2011; Fischer et al., 2012;

Marteau, 2017). Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein first popularised the term

‘nudge’ in the book Nudge: Improving Decisions

About Health, Wealth, and Happiness (2008), in reference to any

characteristic of the decision environment “that alters people’s behaviour in a

predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their

economic incentives” (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008, p.6). Sunstein (2013) further

suggested that nudges can be promising tools for promoting a broad range of

pro-environmental and sustainable consumption behaviours (Sunstein, 2013).

Nudging

interventions can play an important role in sustainable food consumption (SFC),

helping change consumers food habits in a non-obtrusive, cost-effective manner

by modifying the choice architecture in which consumers operate – thus steering

their behaviour in preferred directions (Torma et al., 2018; Kácha and Ruggeri,

2019; Vandenbroele, et al., 2019). Hence nudges are the opposite of coercive

policy tools which tackle behaviour change through fines or bans (Ferrari, et

al., 2019). Blumenthal-Barby and Burroughs (2012) describe the ethical issues

surrounding the MINDSPACE framework and identify six principles that can be

used to nudge people: defaults (D); ego and commitment (EC); incentives (I);

messenger and norms (MN); priming (P); and salience and affect (SA) (BIT, 2010;

Blumenthal-Barby and Burroughs, 2012). Descriptive norms, such as incentivising

tools for online shopping, can help encourage pro-environmental behaviour and

the purchasing of green products (Demarque et al., 2015) whilst social norm

interventions, such as those around the use of reusable cups, can help

customers avoid wasteful disposable items (Loschelder, et al., 2019). D and P

nudges, such as visibility, positioning, display area size and quantity, can

shift consumers’ purchase behaviour towards more sustainable choices (Coucke,

et al., 2019), whereas environmentally friendly food packaging can produce

overall positive impacts on consumers’ sustainability choices (Ketelsen, et

al., 2020).

Nudging

is still in its infancy. The UK established the Behavioural Insight Team in

2009 to help develop the concept of nudge units, initiatives and networks,

whilst The World Bank, OCED and the EU have supported research to further

examine the potential of nudging (Hansen, 2016). Policymakers utilise nudges to

help design, implement and evaluate the appropriate policy instruments to

assist in devising effective policies to enhance sustainable behaviour and

counteract the negative impact of other actors who encourage ‘undesirable’

behaviours (Lehner et al., 2016; Marteau, 2017). However, nudging has been

challenged and criticised on a number of grounds, including the lack of

empirical evidence proving its effectiveness, the difficulty in putting theory

into practice, and for ethical reasons – i.e. paternalism and reduced human

autonomy (Hansen, 2016; Kasperbauer, 2017).

Existing

systematic reviews (SR) undertaken on nudging interventions on food choices

have mainly focused on human health and diet (Bucher et al., 2016; Wilson et

al., 2016; Broers et al., 2017; Bianchi et al., 2018; Taufika et al., 2019;

Vecchio and Cavallo, 2019), and the environmental impacts on the supply chain

(Ferrari et al., 2019). For example, Ferrari et al. (2019) showed that ‘green

nudging’, especially D, NM, P and SA, has the most significant effect on

leveraging more sustainable practices and behaviours of both farmers and

consumers, having the potential to be used as tools for environmental policy

formulation (Ferrari et al., 2019). Bucher et al. (2016), Broers et al. (2017)

and Bianchi et al. (2018) illustrated how altering placement of food items can

produce a moderate significant effect on promoting healthier eating behaviours

through healthier food choices. Bucher et al. (2016) further suggested that the

strength of the nudge depends on the type of positional manipulation, the

magnitude of the change and how far away foods are placed (Bucher, et al.,

2016; Broers et al., 2017; Bianchi et al., 2018). Bianchi et al., (2018)

additionally demonstrated that SA, I and P could increase consumers plant-based

choices by 60-65% (Bianchi et al., 2018). Wilson et al. (2016) illustrated that

the combination of P and SA enable consistent positive influences on healthier

food and beverage choices, making healthier options easier to choose both

mentally and physically (Wilson et al., 2016). Furthermore, Taufika et al.

(2019) illustrated that the combination of SA and MN could be associated with

the reduction of meat consumption (Taufika et al., 2019). Vecchio and Cavallo

(2019) suggested that, overall, nudge strategies successfully increased healthy

nutritional choices by 15.3% (Vecchio and Cavallo, 2019).

Although

these results show that nudges are generally effective in promoting healthier

food choices and sustainable practices and behaviours, none of the studies

examined the effectiveness of nudging interventions on SFC. There is a

knowledge gap on the effectiveness of nudging interventions on sustainable food

choices. The goal of this systematic review is to synthesise the empirical findings

of existing published academic literature that has investigated the effect of

various nudging interventions on these choices and therefore upon SFC in

real-life contexts. This paper will:

- examine

the evidence around the effectiveness of interventions for SFC

- show

the factors that influence the effectiveness of interventions

- help

identify research gaps in current understanding of the field

(Peričić-Poklepović & Tanveer, 2019; CEE, 2020)

Methodology

A

search was conducted to identify published literature that utilised

interventional and experimental studies to examine nudging interventions to

encourage SFC. The studies were identified using the search strategy and

analysed against inclusion criteria, those studies that met these criteria were

further synthesised by analysing abstracts and full texts. Type of nudges

applicable were D, EC, I, MN, P and SA.

Search strategy

This

systematic review was conducted in September 2020. The search terms used to

identify literature from data sources were:

“nudge*”

OR “nudging” OR “nudging theory” AND “sustainable* consumption” AND “food” OR

“diet” AND “consumer”.

Using

these search terms, published literature were retrieved from online databases,

Web of Science, Scopus, ScienceDirect, EBSCO (Bournemouth University Library)

and Google Scholar[1]. The title and abstracts of the retrieved

articles were screened for relevance. The potentially relevant articles were

examined for their eligibility to be included in the review, whilst the

references of the eligible literature were screened to identify any additional

eligible literature.

Language and

date restrictions

Publication

dates were restricted to between 2010-2020 in order that only material released

after the publication of Thaler and Sunstein’s (2008) techniques was

considered. Only literature published in English were included.

Selection

criteria

The

inclusion criteria for selecting eligible literature were:

- Full

test peer-reviewed studies in English language

- Primary

studies between 2010-2020

- Studies

should examine the effectiveness or impact of nudges on sustainable food

choices

- Randomised

control trial studies or have a ‘control’ to ensure empirical evidence

- The

study should measure sustainable food choices as one of its outcomes via

dietary choices i.e., less meat more vegetables

‘Grey’

literature such as reports and letters were excluded as they were not

peer-reviewed.

Selection

process

A

total of 742 eligible studies were retrieved from the data sources using the

aforementioned search strategy, 6 from Web of Science, 338 from ScienceDirect,

9 from EBSCO (Bournemouth University Library), 379 from Google Scholar and 8

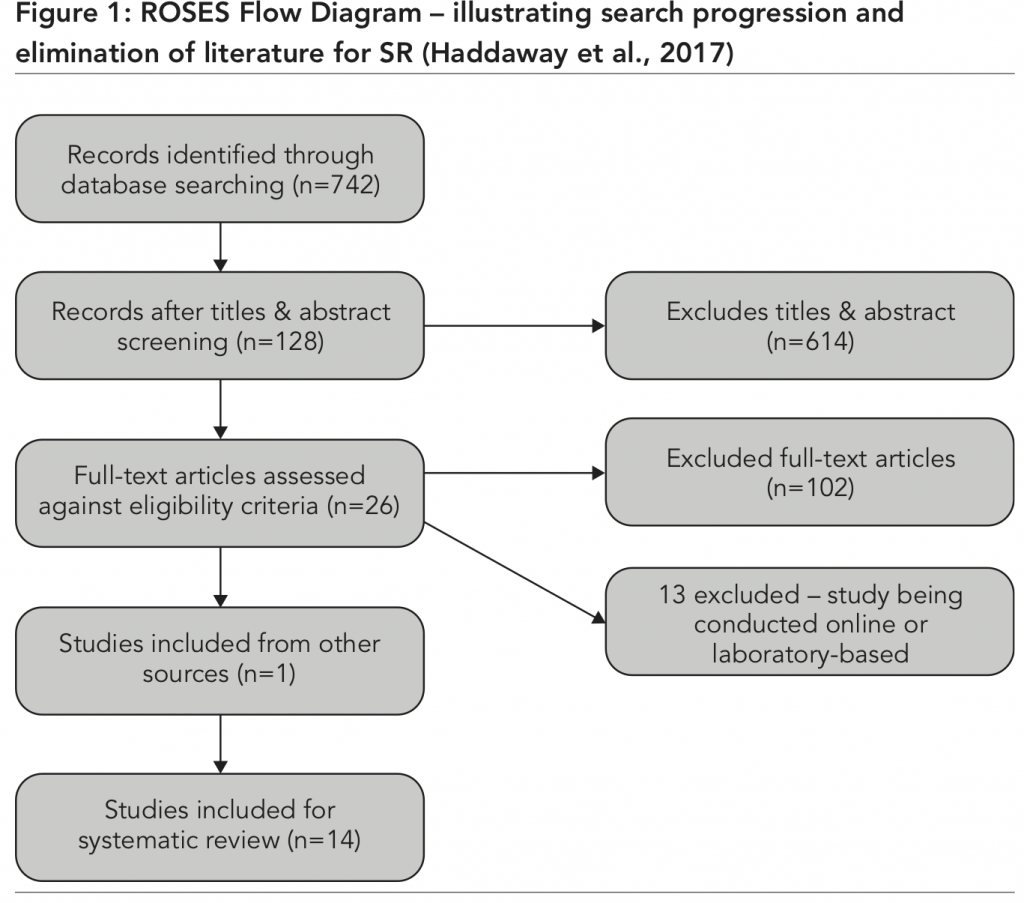

from Scopus. After reviewing titles and abstracts, 614 were excluded (Fig 1).

The remaining 128 studies were assessed against the inclusion criteria,

resulting in exclusion of 102 studies, leaving 26 for further review. 12

articles were further excluded owing to collection of empirical evidence being

conducted in a laboratory setting or online surveys, holding the potential for

behavioural bias, resulting in 14 articles that were based in a naturally

occurring setting i.e., supermarket/canteen. Searching reference lists of the

remaining 13 articles, 1 further article was obtained, creating a total of 14

articles for the SR (Fig 1).

Data extraction and synthesis

From

the 14 eligible articles basic descriptive data were recorded to ensure quality

assessment, including study design, year of data collection, country of

residence, target subjects, sample size and intervention setting. More detailed

data extraction included: intervention strategy; outcome measured; data

analysis method; main findings; and effectiveness of intervention when

evaluated against sustainable food choices i.e., less meat more vegetables.

The

simple mnemonic MINDSPACE framework was utilised to identify the nine robust

nudges that can influence behaviour: messenger; incentive; norms; defaults;

salience; priming; affect; commitments; and ego – MINDSPACE (BIT, 2010). For

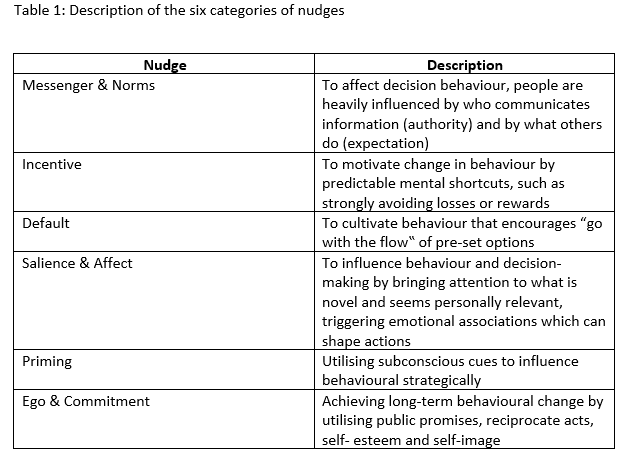

this SR, they have been grouped into six categories – D, EC, I, MN, P and SA

(Table 1) (Blumenthal-Barby and Burroughs, 2012).

There

are many frameworks that help identify key concepts and nudges to influence

behaviour towards healthier choices. The TIPPME framework (Typology of

Interventions in Proximal Physical Micro-Environments) aims to reliably

classify, describe and enable more systematic design, reporting and analysis of

interventions in order to help change behaviour across populations utilising

nudges D, P, SA to change selection, purchase and consumption of foods

(Hollands et al., 2017). Applying EC, MN, SA nudges, the SHIFT framework aims

to encourage consumers into pro-environmental behaviours when the message or

context influences psycological factors, such as social influence, habit

formation, individual self-feeling, cognition and tangibility (White et al.,

2019). Chance et al.’s (2014) The 4P’s framework aims to integrate nudges

within a dual-system model of consumer choice by targeting possibilities,

process, persuasion and person, using nudges D, EC, MN, P, SA. Kraak et al.

(2017) extend this framework by suggesting a marketing mix and choice

architecture 8P’s framework, highlighting the potential to promote and socailly

normalise healthy food environments. This works by utilising nudges D, EC, I,

MN, P, SA encouraging voluntary changes made to the properties of the environment

and food being sold (place, profile, portion, pricing, promotion) and volunatry

changes made to the placement of food sold (healthy default picks,

priming/prompting, proximity (Kraak et al., 2017).

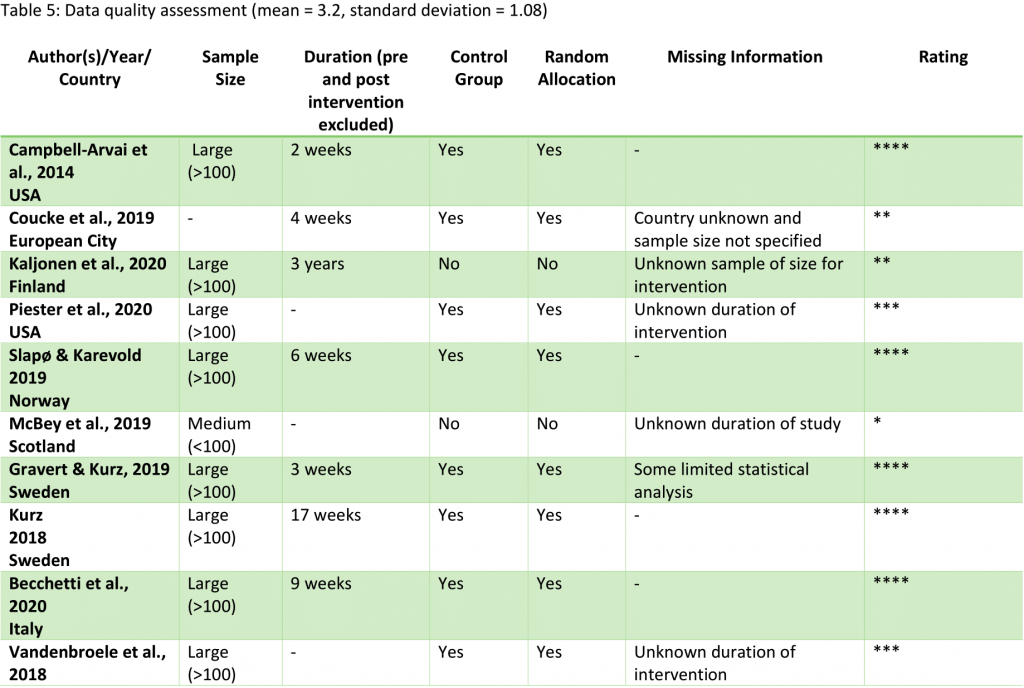

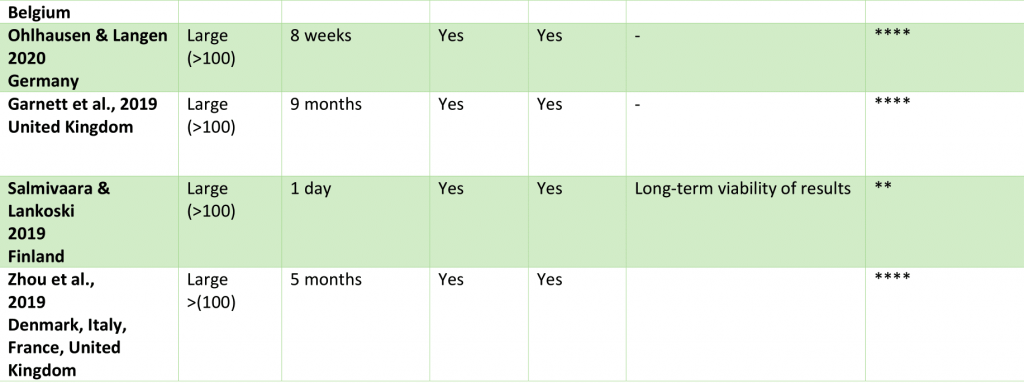

Study quality

assessment

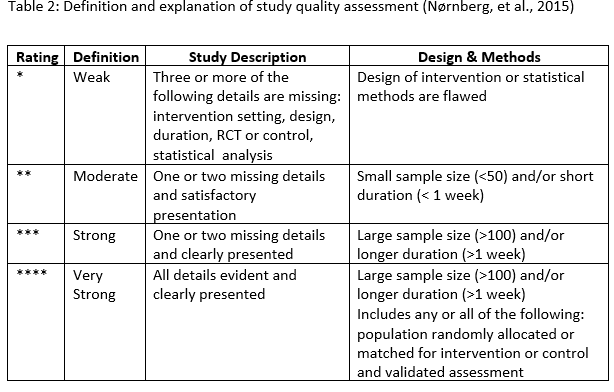

To

assess the quality of data obtained from the eligible studies a rating scheme

was utilised, ranging from weak (*) to very strong (****). The principles of

the ratings were based on study design, selection bias, sample size, duration

of study, and risk of bias from missing information (Table 2). The rating

scheme was adapted from a previous study undertaken by Nørnberg et al. (2015)

who successfully utilised this method to rate and assess the effectiveness of

interventions on vegetable intake in a school setting.

Results

Overall

effectiveness of nudging interventions on SFC

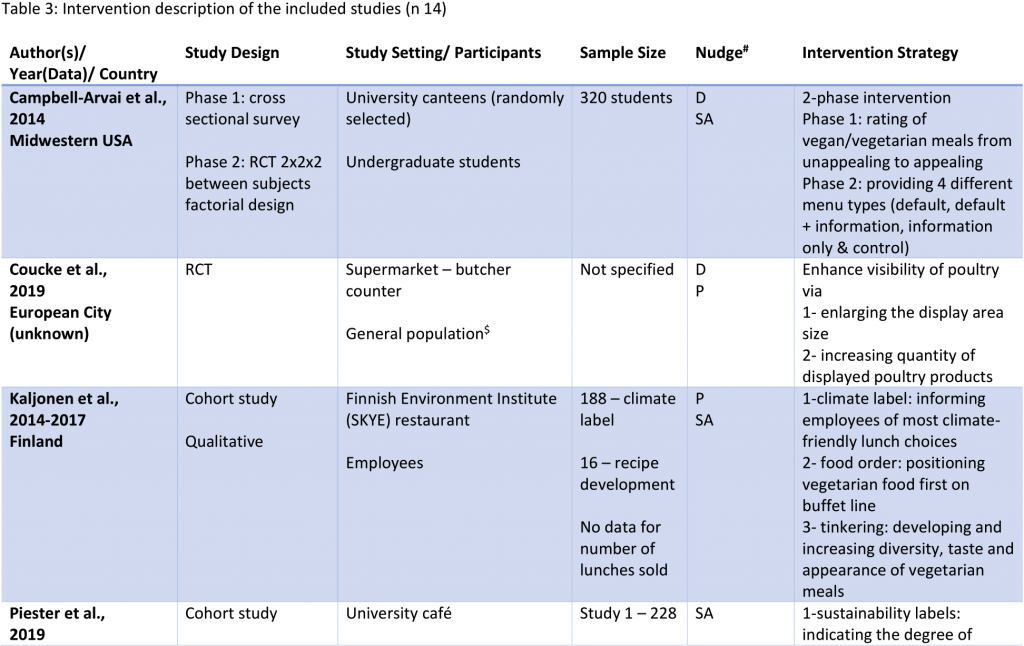

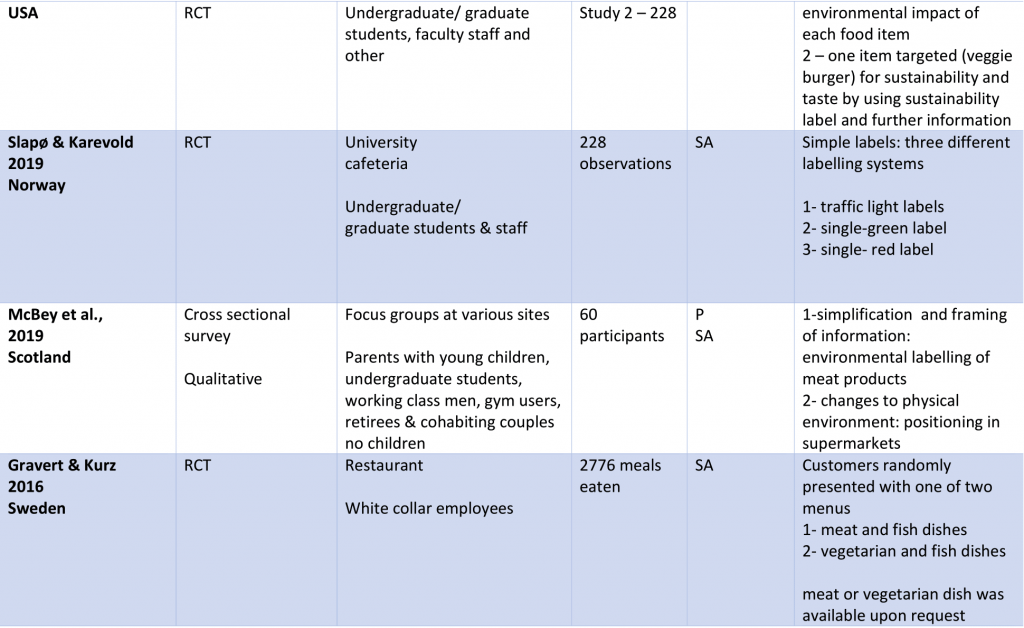

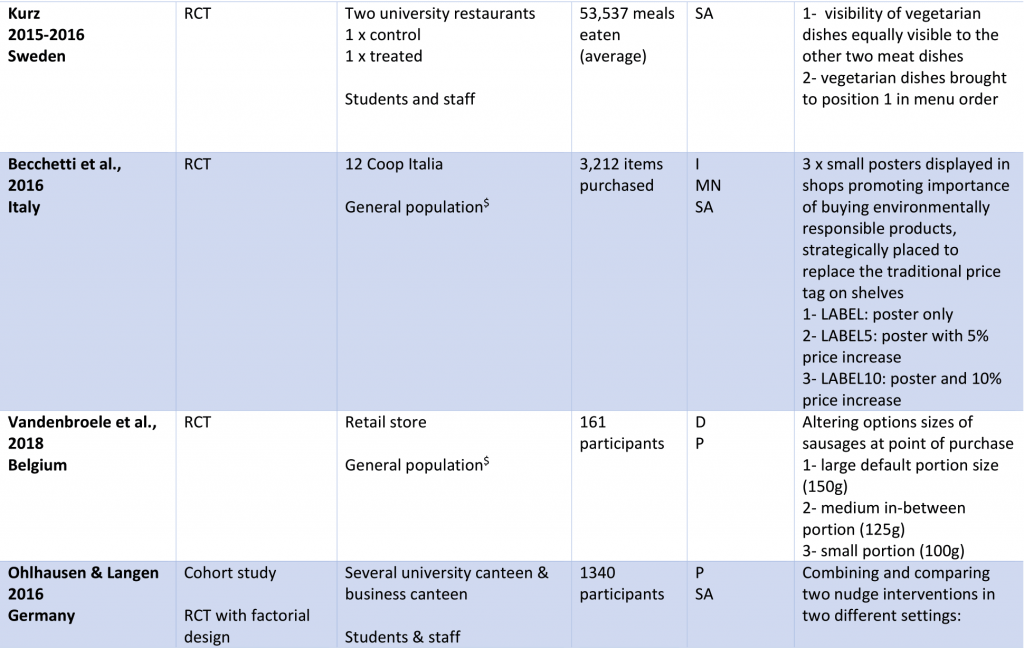

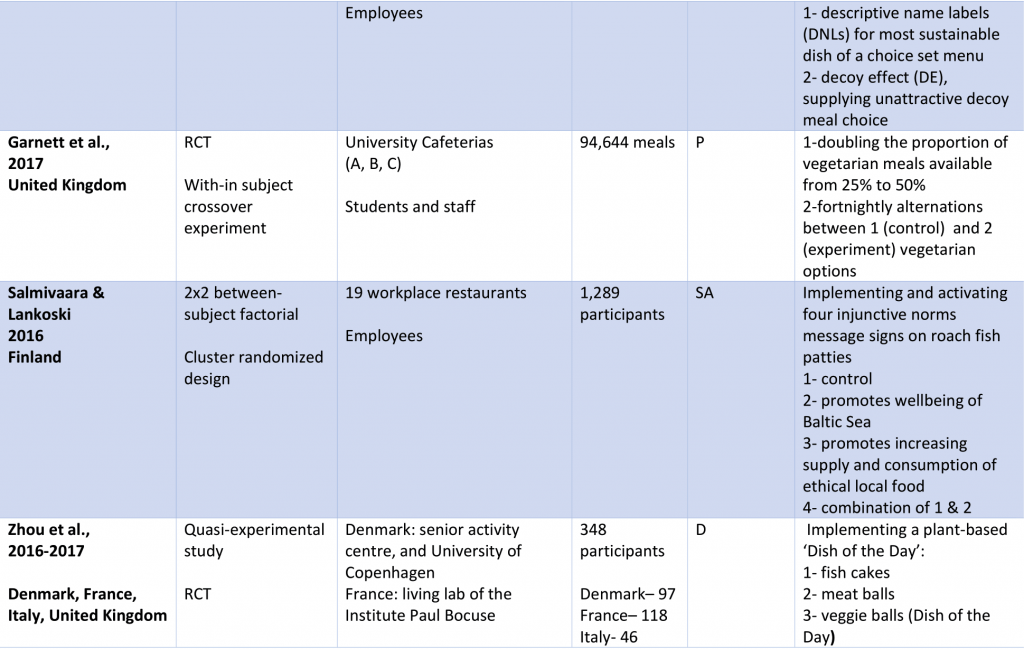

The

14 articles included in this SR all focused on SFC in the form of food choice

behaviour and were conducted in North America and Europe. Interventions were

conducted at supermarkets, canteens, cafeterias, restaurants or cafeterias at

universities, workplace, senior activity centres and the Institute Paul Bocuse.

The subjects consisted of students, university staff, workplace employees,

retirees, and the general population. Five studies used SA as the core nudge,

three used a P/SA combination, two used a D/P combination, one used P, one used

D, one used D/SA combination and one used I/MN/SA combination. The intervention

strategies, intervention duration and sample sizes were largely heterogeneous

across all studies (Table 3).

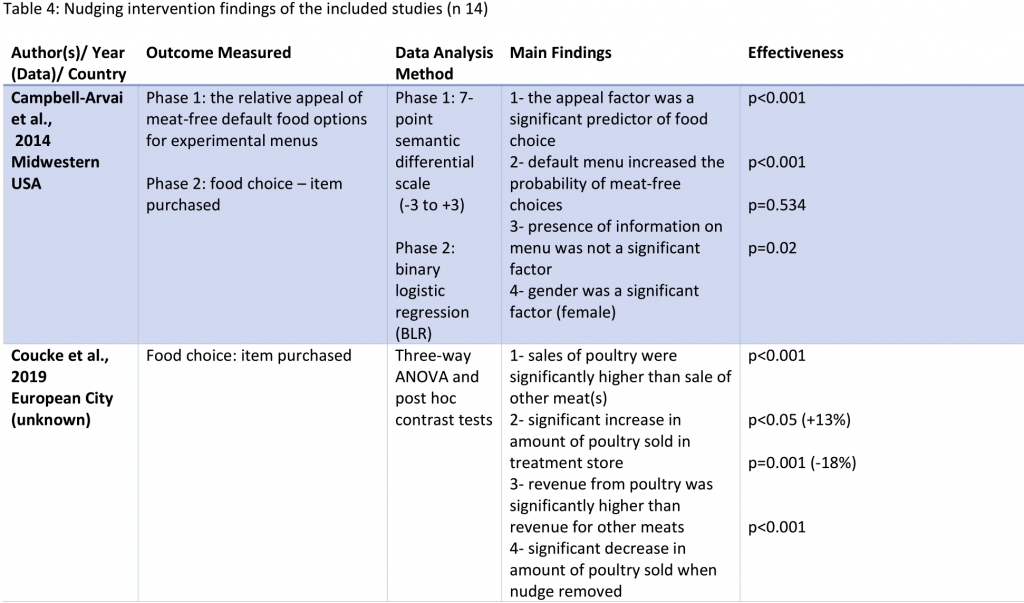

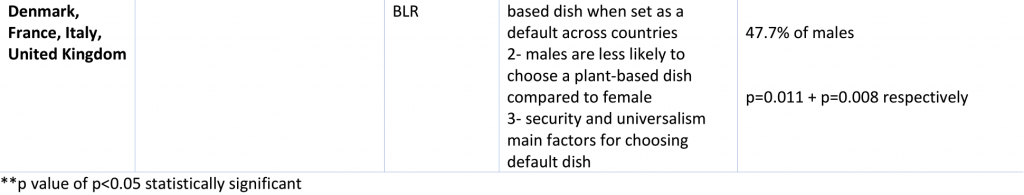

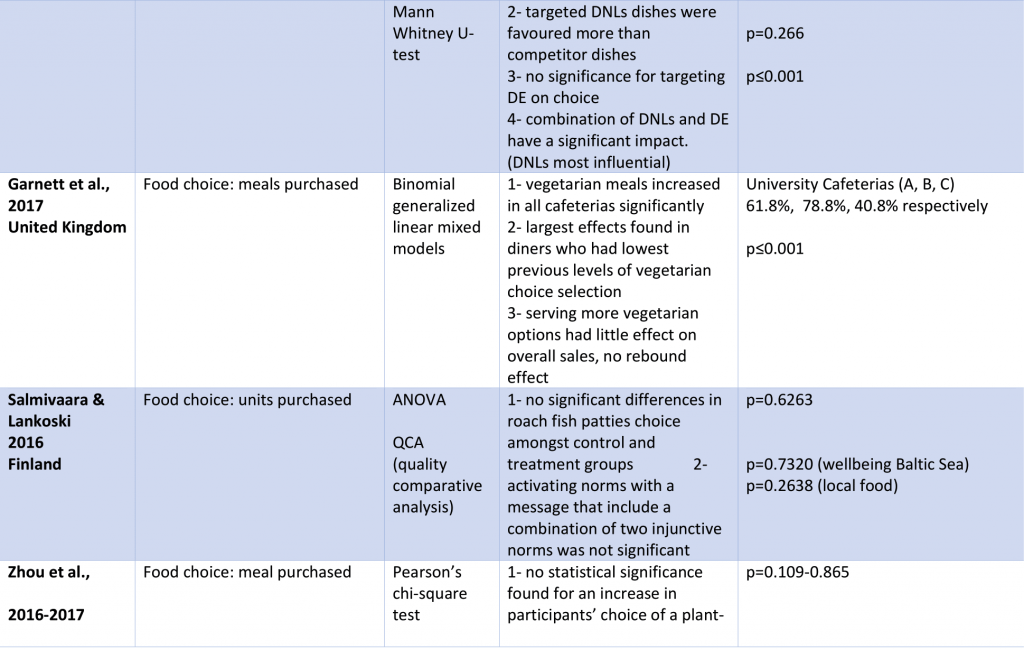

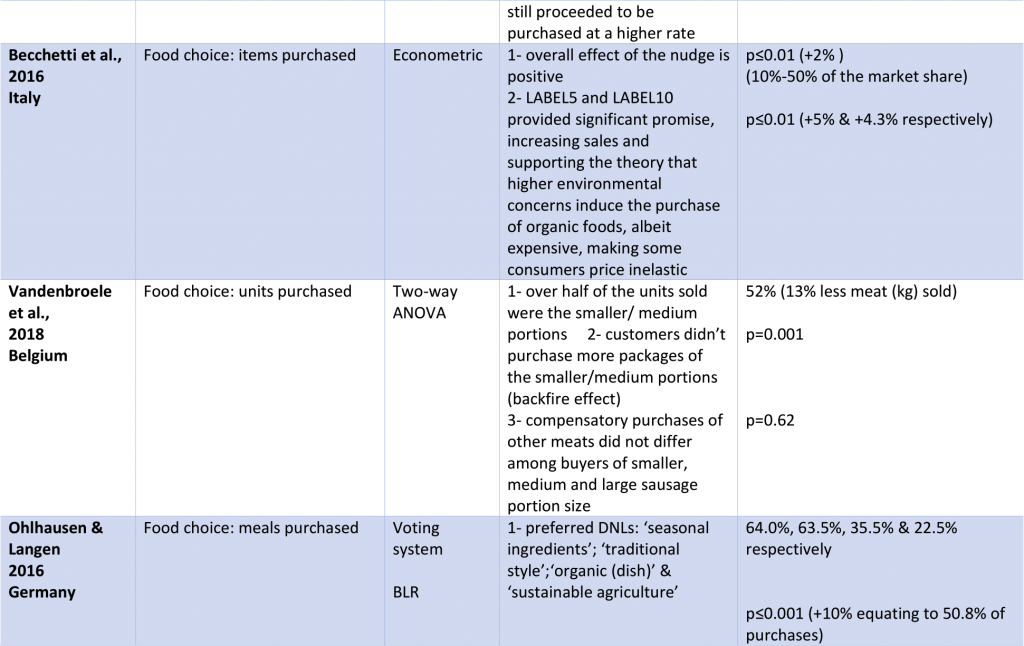

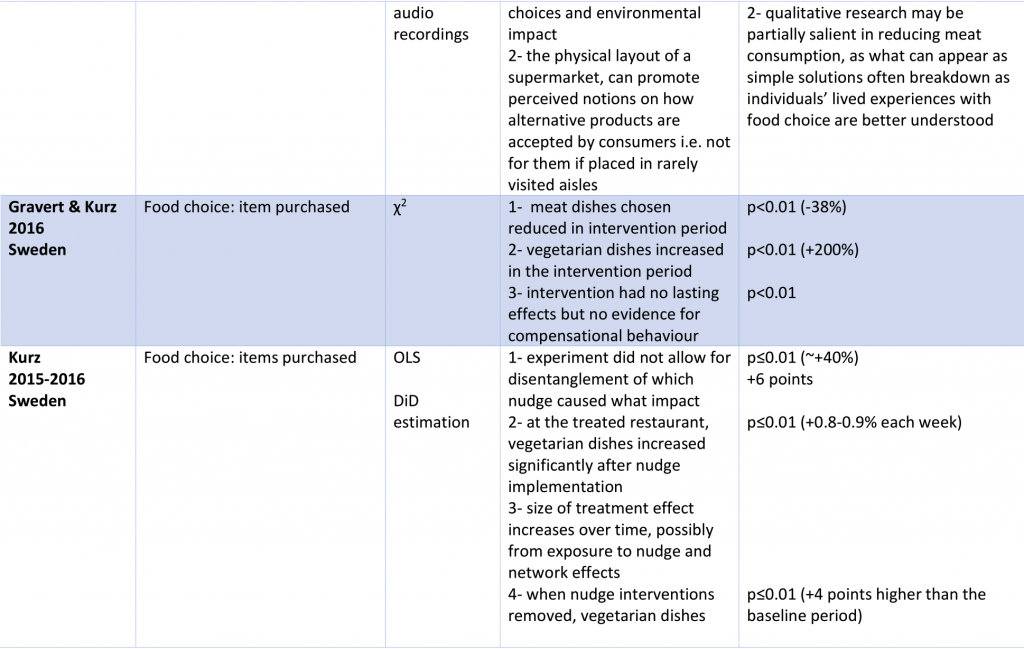

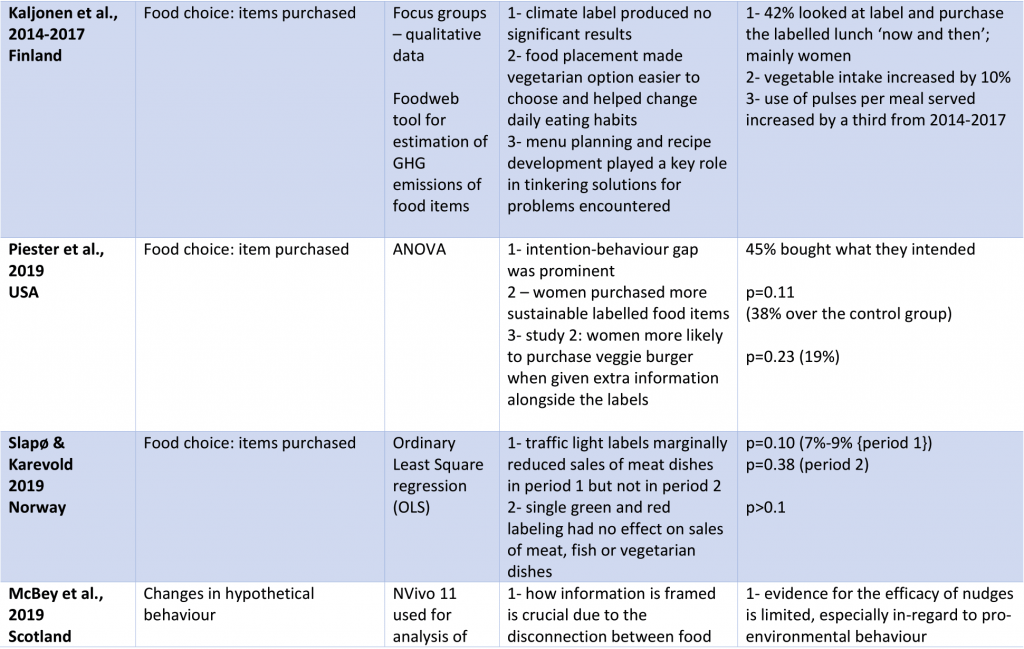

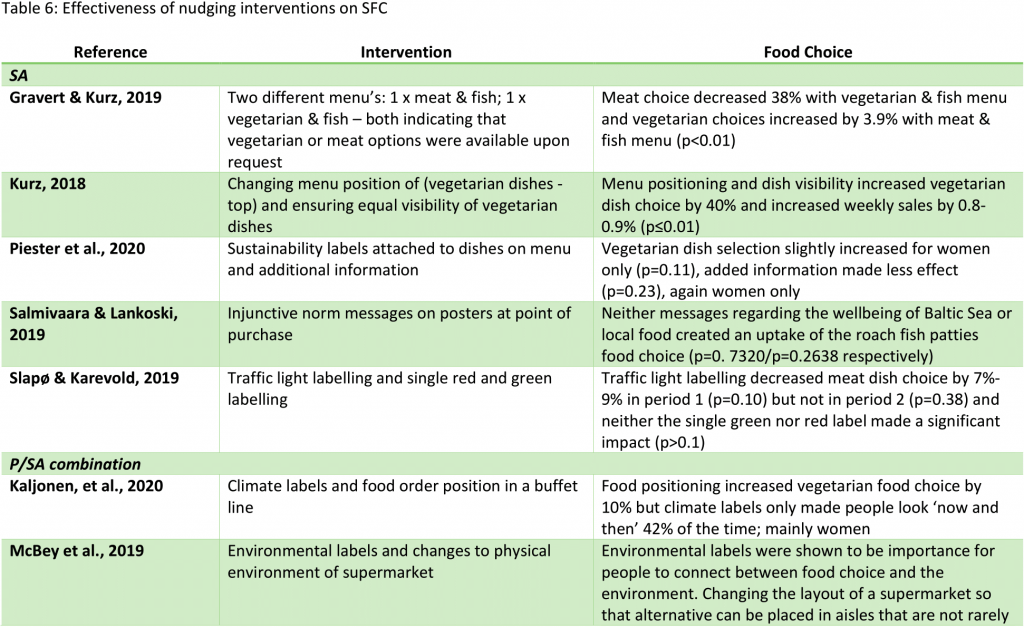

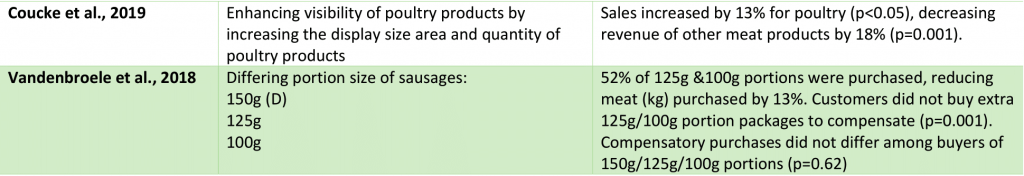

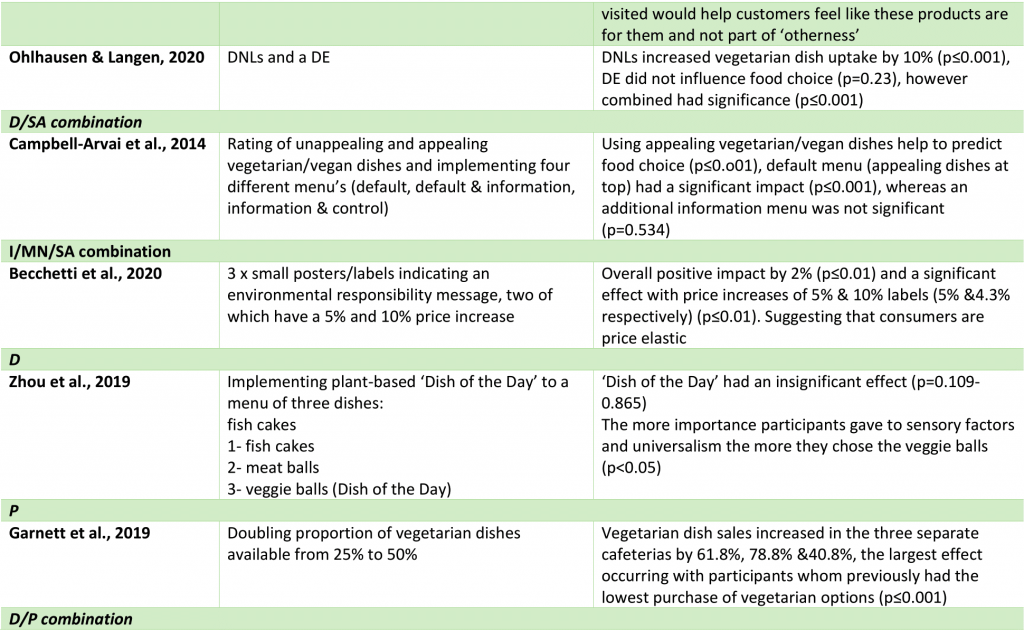

The

different strategies and methods applied to implement the varying nudges

illustrated differing effectiveness (Table 4). The studies utilising nudges SA

(Gravert and Kurz, 2019; Kurz, 2018), P (Garnett et al., 2019), D/P combination

(Coucke et al., 2019; Vandenbroele et al., 2018) and D/SA combination

(Campbell-Arvai et al., 2014) provided statistically significant impact for

increasing sustainable food choices. However, studies that implemented D (Zhou

et al., 2019), P/SA combination (McBey et al., 2019) and SA (Piester et al.,

2020; Salmivaara and Lankoski, 2019; Slapø and Karevold, 2019) were not

statistically significant. One study which utilised P/SA combination (Ohlhausen

and Langen, 2020) showed statistical significance with regards to SA but not P,

whilst a P/SA combination (Kaljonen et al., 2020) and I/MN/SA combination

(Becchetti et al., 2020) illustrated marginal statistical significance, highlighting

the potential use of these combinations.

Data quality

assessment

Twelve

studies were randomised control trials (RCT), duration of interventions varied

considerably, ranging from 1 day to 3 years, three studies did not specify the

intervention duration. All studies, bar one, had a large sample size (˃100)

and one lacked sufficient statistical analysis. The quality rating of the

included studies was strong to very strong with a mean rating of 3.2 and

standard deviation of 1.08 (Table 5).

Sustainable

food choices

In

total, five of the studies utilised the nudge SA to encourage SFC (Kurz, 2018;

Gravert and Kurz, 2019; Salmivaara and Lankoski, 2019; Slapø and Karevold,

2019; Piester et al., 2020). The main strategy utilised consisted of signage,

ranging from descriptive menus to visual environmental information. Gravert and

Kurz (2019) suggested that introducing two different menus, 1 x meat and fish

dishes 1 x vegetarian and fish dishes – meat or vegetarian choices were

available upon request. Meat dish choice decreased by 38% with the vegetarian

and fish menu and vegetarian choices increased (3.9%) with the meat and fish

menu – no compensatory effect was monitored (p˂0.01).

Kurz (2018) found that by changing the position of vegetarian dishes in a menu

order, and allocating equal visibility of vegetarian dishes with meat dishes in

the purchasing environment, purchase of vegetarian dishes increased by 40% (p ≤

0.01). Weekly sales of vegetarian dishes increased by 0.8%-0.9% after the

intervention ceased (p ≤ 0.01) (Kurz, 2018).

Slapø

and Karevold (2019) found that impementing traffic light labelling (red,

yellow, green) on dishes to indicate the environmental friendliness of a dish,

encouraged a 7%-9% reduction in meat sales (p=0.10), although having just

singular green or red labels had little to no impact (p˃0.1).

Salmivaara and Lankoski (2019) indicated that activating injunctive norm

message signs at point of purchase had no significant effect on sustainable

food choice (p=0.6263), whilst Piester et al. (2020) found that implementing

sustainability labels on menus marginally influenced women’s uptake of more

sustainable choices (p=0.11) but not for men (p=0.23). Piester et al. (2020)

identified the intention-behaviour gap, highlighting that only 45% of people

bought the items they intended to purchase.

Three

studies utilised P/SA combination (McBey et al., 2019; Kaljonen et al., 2020;

Ohlhausen and Langen, 2020), applying signage with availability and

accessibility to help encourage more SFC. Kaljonen et al. (2020) suggested that

increasing the availability and accessibility of vegetarian dishes in a buffet

line, placing vegetarian dishes at the front, increased sales by 10%. Climate

labels attached to the dishes had limited effect, although women were more

susceptible (42%). Ohlhausen and Langen (2020) found that DNLs were

statistically significant when in combination with a DE (unattractive meal

dish) (p≤0.001), while DNLs were 10% more influential than the DE. McBey et al.

(2019) proposed that environmental labelling is crucial for framing the disconnection

between food choice and the environmental consequence, and the physical layout

of retail stores can be a powerful tool in promoting SFC to consumers.

A

D/SA combination (Campbell-Arvai et al., 2014) which implemented ‘appealing’

vegan/vegetarian dishes on a menu assisted significantly with the prediction of

food choices made by consumers (p˂0.001), and when

applied into a default menu (appealing dishes positioned at top) sales

increased significantly (p˂0.001); however providing

information-only menus promoted a decrease in meat-free purchases (p=0.534).

Becchetti et al. (2020) utilised a combination of I/MN/SA, implementing three

small posters/labels in-store, one promoting environmental responsibility and

two labels implementing a 5% and 10% price increase on organic items. Overall,

the intervention increased sales by 2% (p≤0.01), with the 5% and 10% labels

increasing sales of organic items by 5% and 4.3% respectively, supporting the

theory that higher environmental concern can induce the purchase of organic

foods, and can induce the purchase of organic food despite its greater cost.

Garnett

et al. (2019) utilised P, doubling the quantity of vegetarian dishes (25% to

50%) available in three university cafeterias. The intervention increased

vegetarian dish uptake by 60.4% across the three cafeterias, positively

impacting consumers whom previously had low levels of vegetarian purchases

(p≤0.001) with no rebound effect. Zhou et al. (2019) used ’Dish of the Day’ as

a D intervention, providing statistically insignificant results (p=109-0.865).

However, they highlighted that the default dish was chosen when concerns such

as security (e.g., safety, harmony, and stability of society, of

relationships, and of self) and universalism (e.g., understanding, appreciation,

tolerance, and protection, for the welfare of all people and for nature) were

strong (p=0.11 and p=0.008 respectively). D/P combination (Coucke et al., 2019;

Vandenbroele et al., 2018) provided statistically significant results. Couke et

al. (2019) increased sales of poultry by 13% (p˂0.05)

and decreased sales of other meats by 18% (p=0.001) via enhanced visibility and

quantity of poultry available at a butcher’s counter. When the intervention

ceased, poultry sales decreased significantly (p˂0.001).

Vandenbroele et al. (2018) illustrated that altering the portion sizes of

sausages (150g, 125g, 100g) increased the purchase of 125g and 100g portions

marginally (52%), with no compensatory effect on customers purchasing extra

portions of the same size (p=0.001). The intervention decreased overall meat

(kg) purchased by 13%, however compensatory purchases of other meats did not

differ amoung buyers of all portion sizes (p=0.62).

Discussion

Effectiveness

of nudging interventions on SFC

Out

of the 14 studies reviewed, ten provided statistically significant results,

supporting the positive effectiveness of nudging interventions in encouraging

sustainable food choices (Table 6).

SA as a

nudge

Gravert

and Kurz, (2019) suggested that the simple and inexpensive rearrangement of

menus in terms of convenience could reduced meat consumption by 38% and

increase vegetarian and fish dishes sold by 200% (p˂0.01).

Kurz (2018) further supported this theory by suggesting that increasing

visibility and changing menu position could encourage a persistent shift in

consumption behaviour (p≤0.01) whereas Löfgren et al. (2012) proposed that

experienced participants were harder to nudge than inexperienced participants.

The heterogenous effects of the nudge in relation to the type of vegetarian

dish served identified that the target dish(es) offered had to be more

attractive to meat eaters, hence vegetarian burgers/patties had the most

successful impact. With that said, disentanglement of which nudge

(visibility/position) caused the vegetarian dish increase was not undertaken.

Conversely,

Piester et al. (2020) found the effectiveness of sustainability labels with

additional information on a menu was not effective, possibly due to the unknown

duration of the intervention and information overload of having messages that

combine different types of information (Carfona et al., 2019). Women were more

likely to purchase vegetarian dishes with sustainability labels (p=0.11), and

with additional information this increased (p=0.23), this is consistent with

past research emphasising gender influence in SFC (Andersen and Hyldif, 2015;

Zhou, et al., 2019). Piester et al. (2020) highlighted that only 45% of

participants purchased what they intended, hence the intention-behaviour gap of

consumers is crucial in understand purchasing habits (ElHaffar et al., 2020;

Rausch and Kopplin, 2021).

Slapø

and Karevold (2019) provided marginally significant results utilising traffic

light labelling, supporting the theory of the ‘compromise effect’ (choosing the

middle option) (Carroll and Vallen, 2014). Initially there was 7-9% reduction

in meat consumption (p=0.10), this behaviour declined over time and almost

reverted back to the control period behaviour after period 1; providing

evidence that consumers can develop “label fatigue” (p=0.38) (Thorndike et al.,

2014). Single red and green labels had no signficant impact (p˃0.1),

possibly due to lack of available environmental information (Ratner et al.,

2008), limited previous knowledge regarding the connection between food choices

and environmental consequences (Hartmann and Siegrist, 2017; Lea et al., 2006)

and perceived needs of consumers in the choice situation (i.e. focused on

sensory factors rather than environmental preservation) (Andersen and Hyldif,

2015; Slapø and Karevold, 2019).

Salmivaara

and Lankoski (2019) concurred with these results, suggesting that activating

injunctive norm messages to promote sustainable food choice is an ineffective

measure (p=0.6263), possiblly due to the 1-day intervention duration and

exclusion of vegetarian and vegan participants. Nevertheless, this intervention

could help identify potential subgroups of consumers who are sensitive to the

intervention, i.e. older educated women influenced more by the message of

“ecological wellbeing”. Multiple norms could have complex casual interactions

and joint effects, i.e. messages of ecological wellbeing and local food could

be combined to have greater impact than the message used independently; a topic

requiring further attention (McDonald et al., 2014).

P/SA

combination as a nudge

Ohlhausen

and Langen (2020) were able to identify the SA nudge (DNLs) as 10% more

effective in increasing vegetarian dish choice (p≤0.001), especially the use of

“sustainability” and “regional” (20% and 15% respectively), proving consistent with

past research (Morizet et al., 2012). Whereas, in constrast to previous

non-food related literature, the P nudge (DE) lowered choice frequencies of

sustainable choices overall (p=0.23) (Simonson, 1989; Doyle et al., 1999;

Masicampo and Baumeister, 2008). This study supports Kurz (2018) theory that

nudging interventions are not only influenced by the type of nudge or setting

but by other variables (i.e. target dish), hence based on systematic assessment

of similarities and difference between dishes, careful selection and grouping

of target dishes and competitor dishes is required (Ohlhausen and Langen,

2020).

Both

Kaljonen et al. (2020) and McBey et al. (2019) undertook qualitative studies

that used descriptive labels as the SA nudge. Kaljonen et al. (2020) suggested

that climate labels are a restriction to menu and recipe development, whilst

McBey et al. (2019) suggested that how descriptive messages are framed is

crucial, i.e. comparing meat products with sources of environmental pollution.

Kaljonen et al. (2020) further suggested that availability and accessibility,

by changing the food order available in a buffet line (P nudge), helps to

encourage more vegetarian dish choices (+10%). Coinciding with McBey et al.

(2019) who suggested that the physical layout of supermarkets play a pivotal

role in highlighting the ‘otherness’ of alternative food choices (i.e.

plant-based), creating a ‘not for me’ implication. Both studies agreed with

past research that more qualitative research is required in understanding SFC

(Lehner et al., 2016), the complex and multi-faceted nature of food choice

means that what holds true in controlled conditions may not work in every day

life (Kahneman, 2011).

D/SA

combination as a nudge

Campbell-Arvai

et al.’s (2014) D/SA combination suggested that by placing less

environmentally-friendly food choices in slightly less convenient positions on

a menu (i.e. bottom) the default menus increased the probablility of consumers

choosing a meat-free dish (p≤0.001). This was consistent with other research

(Downs et al., 2009; Just and Wansink, 2009). The attractiveness of menu dishes

had a significant influence on food choice enabling prediction of the choice

(p≤0.001), whereas the presence of information on a default menu provided

statistically insignificant interactions (p=0.534). Additional information is

less effective at motivating behaviour change at an individual-scale and with

real time choices due to immediate or intuitive factors that dominate

decisions, especially when time pressure and distractions conspire to prevent

personal deliberation (Shiv and Fedorikhin, 1999; Ariely and Loewenstein,

2006). The study design did not record ‘actual’ food choice or consumption,

hence exaggeration of environmentally-friendly behaviour could have occurred

(de Boer et al., 2009; Bray et al., 2011).

I/MN/SA

combination as a nudge

As

previously discussed, Becchetti et al. (2020) provided marginally significant

results when implementing three posters/labels, highlighting the effectiveness

of consumers environmental responsibility (+2%; p≤0.01). These findings

exceeded the results of Hainmueller et al.’s (2015) study. Consumers believe

that this form of intervention can affect other consumers choices by up to 80%,

coinciding with the theory that social norms have strong effects on consumer

purchasing habits (Collins et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019).

D as a nudge

Zhou

et al.’s (2019) ‘Dish of the Day’ (veggie balls) intervention provided

statistically insignificant results across four countries (p=0.109-0.865). This

is in contrast to many studies that have shown that D nudges can promote

healthier purchase behaviour (McDaniel et al., 2001; Feldman et al., 2011). The

unappealing nature of the veggie balls could have resulted from a lack of

detailed information accompanying the dish and the equality it was given

amongst the other two dishes, lowering participants’ attention to the default

dish. Females from the UK and Denmark were more likely to choose the D target

dish, especially when more importance was given to sensory factors and

universalism (p=0.042 and p=0.033), supporting the view that peoples’ concern

about nature could be effective for SFC (Worsley et al., 2016). Zhou et al.

(2019) highlighted that default-based interventions can be important tools in motivating

pro-environmental behaviour and serve to complement information and educational

efforts over the long-term. However, this could be seen as underhanded and

choice constraining, limiting freedom and autonomy of decison makers.

P as a nudge

P as

a nudge has the potential to encourage SFC, it is a relatively cheap and easily

implemented strategy that generally goes unnoticed by consumers. Garnett et al.

(2019) highlighted that meal selection is neither fixed nor random but rather

partially determined by availability. By increasing the proportion of

vegetarian choice uptake significantly increased, reflecting past research

(Holloway et al., 2012; Lombardini and Lankoski, 2013; Bianchi et al., 2018).

The greatest impact was measured amongst participants who were least likely to

chose vegetarian dishes before the intervention (p≤0.001), corresponding with

Scarborough’s findings (2014).

D/P

combination as a nudge

Both

Coucke et al. (2019) and Vandenbroele et al. (2018) provided statistically

significant results for encouraging sustainable food choice (p˂0.05

and p=0.001 respectively), however the studies lacked information on either

sample size or duration. Vandenbroele et al. (2018) suggested that nudging

consumers at point of purchase, rather than at moment of consumption, led to a

13% reduction in meat (kg) purchased and helped to change consumers purchase

behaviour, concurring with previous research (Arno and Thomas, 2016; Vermeer et

al., 2010). Coucke et al. (2019) supported this theory by suggesting that

increasing the display size and quantity of more sustainable meat products

(poultry), increased sustainable choices (+13%). When the intervention was

removed sales of the sustainable meat product decreased, highlighting that

visual cues can have an impact on consumers behaviour (Van Kleef et al., 2012;

Wilson et al., 2016; Helmefalk and Berndt, 2018). Overall, D/P combination is

an effective nudge for promoting and encouraging consumers to change their

behaviour to more SFC practices.

Conclusion

Overall,

this review has established the potential of certain nudging interventions for

encouraging sustainable food choices and SFC. Strategies that required little

involvement (system 1) from consumers, produced higher statistically

significant outcomes compared to nudging interventions which required more

deliberation (system 2). Gender, sensory factors, attractiveness, and type of

target dish played a pivotal role in encouraging sustainable food choices.

Females were influenced by interventions significantly more than males.

Proximity, placement, and information encouraged consumers to adopt more

sustainable food choices and the overall presentation, portion size and choice

of sustainable alternatives played a key role in encouraging consumers into SFC.

Successful nudges included P, D/P combination, SA, D/SA combination and I/MN/SA

combination. These five nudges utilised intervention strategies that enhancing

availability and accessibility, promoted consumers environmental

responsibility, altered portions sizes, offered food alternatives upon request,

and targeted appealing dishes in combination with a default menu. Five studies

that utilised D, SA combination and P/SA combination all provided insignificant

results. Interventions such as ‘Dish of the Day’, activating injuctive norms

and sustainability labels, with additional information, proved ineffective

tools for promoting sustainable food choices. The effectiveness of nudging is

optimal when utilsied together with information campaigns, economic incentives

and education, and hindered by factors including bias, intention-behaviour gap

and external influences such as social norms, environmental determinants and

financial status (Broers et al., 2017; Taufika et al., 2019).

This

SR had several limitations. The search terms “nudges, nudging or nudge theory”

may have lead to many undetected studies being left out, as well as

“behavioural interventions” not being included in the search strategy may have

limited the outcome. The studies were mainly heterogeneous with different

interventions measured. Participants were mainly students or staff and the

intervention settings were primarily universities, restricting greater external

validity. All of the studies were undertaken in developed and highly

westernised countries, hence further research should be undertaken in

developing countries to allow for better understanding of the effectiveness of

nudging interventions. Only English papers were eligible, hence a possibility

of missing important relevant studies in other languages. Furthermore, this SR

has been conducted by a single reviewer which could potentially cause bias on

screening, rating and synthesis of the studies.

All

of the studies, bar one, focused on short-term effectiveness of nudging and

thus more research should be undertaken to understand if nudging is

effective in the long-term. Further research regarding gender, sensory

influences, dish attractiveness, multiple norms, intention-behaviour gap and

tinkering could be addressed in conjuction with nudging interventions to better

understand how more sustainable eating can be achieved in real-life situations,

strengthening evidence and knowledege of how nudging might encourage SFC.

Further

qualitative research should also be undertaken to enable greater understanding

of what occurs in non-controlled environments. Ethical consideration of nudging

and transparency is required in any future use of the technique in order to

address the issue of freedom or autonomy in decision-making.

The

number of people that can be supported within planetary boundaries in part

depends on their choices (Cohen, 2017). The massive environmental impact of

agriculture and the food industry mean that food choices will become of

increasing importance. People are at the centre of sustainable development and

with global population projected to increase to 9.7 billion by 2050 (United

Nations, 2019), individual and collective human choices coupled with

environmentally sustainable practices will be key drivers to enable a

sustainable expansion in food production (Cohen, 2017). Nudging may play a role

in changing behaviour toward habits of sustainable food consumption.

Acknowledgements

I

would like to thank Professor Adrian Newton, his support, guidance, and

patience made it possible to complete this review. I would also like to

acknowledge the contributions of the two anonymous reviewers and JP&S

editor David Samways in developing this paper. My thanks also to family and

friends for their support.

Notes

[1] “effectiveness” AND “interventions”

included for ScienceDirect and Google Scholar due to large size of articles

found. ScienceDirect did not accept wildcards (*).

References

Allcott,

H. and Mullainathan, S., 2010. Behaviour and energy conservation. Science, 327(5970),

pp. 1204-1205.

Alsaffar,

A., 2016. Sustainable diets: the interaction between food industry, nutrition,

health and the environment. Food Science And Technology

International, 22,

pp.102-111.

Andersen,

B. and Hyldif, G., 2015. Consumers’ view on determinants to food satisfaction.

A qualitative approach. Appetite, 95, pp.9-16.

Ariely,

D. and Loewenstein, G., 2006. The heat of the moment: the effect of sexual

arousal on sexual decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision

Making, 19,

pp.87-98.

Arno,

A. and Thomas, S., 2016. The efficacy of nudge theory strategies in influencing

adult dietary behavior: asystematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 16,

pp.676-687.

Beattie,

G. and McGuire, L., 2016. Consumption and climate change: Why we say one thing

but do another in the face of our greatest threat. Semiotica, 213,

pp.493-538.

Becchetti,

L., Salustri, F. and Scaramozzino, P., 2020. Nudging and corporate

environmental responsibility: a natural field experiment. Food Policy, 97 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101951

Benton,

T., 2016. What will we eat in 2030? World

Economic Forum. [Online]

Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/11/what-will-we-eat-in-2030/

[Accessed 25 August 2020].

Bianchi,

F. et al., 2018. Interventions targeting conscious determinants of human

behaviour to reduce the demand for meat: a systematic review with qualitative

comparative analysis. International Journal of

Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 15(102), pp.1-25.

Bianchi,

F. et al., 2018. Restructuring physical microenvironments to reduce the demand

for meat: a systematic review and qualitative comparative analysis. Lancet Planet Health, 2, pp.384-397.

BIT,

2010. MINDSPACE Influencing behaviour

through public policy, London:

Cabinet Office.

Blumenthal-Barby,

J. S. and Burroughs, H., 2012. Seeking better health care outcomes: the ethics

of using the “nudge”. The American Journal of

Bioethics, 12(2),

pp.1-10.

Bolos,

L. A., Lagerkvist, C. J. and Nayga Jr, R. M., 2019. Consumer choice and food waste:

can nudging help?. Agricultural and Applied

Economics Association, 34(1),

pp.1-8.

Bray,

J., Johns, N. and Kilburn, D., 2011. An exploratory study into the factors

impeding ethical consumption. J. Business Ethics, 98, pp.597-608.

Broers,

V. J., De Breucker, C., Van den Broucke, S. and Luminet, O., 2017. A systematic

review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of nudging to increase fruit and

vegetable choice. European Journal of Public

Health, 27(5),

pp.912-920.

Bucher,

T. et al., 2016. Nudging consumers towards healthier choices: a systematic

review of positional influences on food choice. British Journal of Nutrition, 115, pp.2252-2263.

Campbell-Arvai,

V., Arvai, J. and Kalof, L., 2014. Motivating sustainable food choices: the role

of nudges, value orientation, and information provision. Environment and Behavior, 46(4), pp.453-475.

Campos,

S., Doxey, J. and Hammond, D., 2011. Nutrition labels on. Public Health Nutr, 14,

pp.1496-1506.

Carfona,

V., Catellani, P., Caso, D. and Conner, M., 2019. How to reduce red processed

meat consumption by daily text messages regarding environment or health

benefits. Journal of Environmental

Psychology, 65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101319

Carroll,

R. and Vallen, B., 2014. Compromise and attraction effects in food. Int. J. Consumer Stud, 38, pp.636-641.

CEE,

2020. Aims and Scope. [Online] Available at: http://www.environmentalevidence.org/guidelines/aims-and-scope

[Accessed 26 August 2020].

Chance,

Z., Gorlin, M. and Dhar, R., 2014. Why choosing healthy foods is hard, and how

to help: presenting the 4Ps framework for behavior change. Cust. Need. and Solut, 1, pp.253-262.

Collins,

E. et al., 2019. Two observational studies examining the effect of a social

norm and a health message on the purchase of vegetables in student canteen

settings. Appetite, 132, pp.122-130.

Coucke,

N., Vermeir, I., Slabbinck, H. and Van Kerckhove, A., 2019. Show me more! The

influence of visibility on sustainable food choices. Foods, 8(186),

pp.1-12.

Davis,

K. F. et al., 2016. Meeting future food demand with current agricultural

resources. Global Environmental Chang,. 3, pp.125-132.

de

Boer, J., Boersema, J. J. and Aiking, H., 2009. Consumers’ motivational

associations favouring freee-range meat or less meat. Ecol. Econ, 68,

pp.850-860.

de

Grave, R. et al., 2020. A catalogue of UK household datasets to monitor transitions

to sustainable diets. Global Food Security, 24, p.100344.

Demarque,

C., Charalambides, L., Hilton, D. and Waroquier, L., 2015. Nudging sustainable

consumption: The use of descriptive norms to promote a minority behavior in a

realistic online shopping environment. Journal of Environmental

Psychology, 43,

pp.166-174.

Downs,

J. S., Loewenstein, G. and Wisdom, J., 2009. Strategies for promoting healthier

food choices. American Economic Review, 99, pp.159-164.

Doyle,

J., O’Connor, D., Reynolds, G. and Bottomley, P., 1999. The robustness of the

asymmetrically dominated effect: Buying frames, phantom alternatives, and

in−store purchases. Psychol. Mark, 16, pp.225-243.

ElHaffar,

G., Durifa, F. and Dubé, L., 2020. Towards closing the attitude-intention-behavior

gap in green consumption: a narrative review of the literature and an overview

of future research directions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122556

Ethical

Consumer, 2018. Ethical consumer market report. Manchester: Ethical Consumer.

FAO,

2019. Sustainable healthy diets

guiding principles. Rome:

WHO.

FAO,

et al., 2020. The state of food security and

nutrition in the world 2020. Transforming food systems for affordable healthy

diets. Rome:

FAO.

Feldman,

C. et al., 2011. Menu engineering: a strategy for seniors to select healthier

meals. Perspectives in Public Health, 131(6), pp.267-274.

Ferrari,

L., Cavaliere, A., De Marchi, E. and Banterle, A., 2019. Can nudging improve

the environmental impact of food supply chain? A systematic review. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 91, pp.184-192.

Fischer,

J. et al., 2012. Human behaviour and sustainability. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 10(3), pp.153-160.

Garnett,

E. E. et al., 2019. Impact of increasing vegetarian availability on meal

selection and sales in cafeterias. PNAS, 116(42), p.20923–20929.

Gravert,

C. and Kurz, V., 2019. Nudging à la carte: a field experiment on

climate-friendly food choice. Behavioural Public Policy, 5(3) pp.378 – 395. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2019.11

Haddaway,

N., Macura, B., Whaley, P. and Pullin, A., 2017. ROSES Flow diagram for systematic reviews, Version 1.0. doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.5897389.v3.

Hainmueller,

J., Hiscox, M. and Sequeira, S., 2015. Consumer demand for fair trade: evidence

from a multistore field experiment. Rev. Econ, 97(2), pp.42-256.

Hansen,

P. G., 2016. What is nudging? Behavioral

Science and Policy Association. [Online]

Available at:

https://behavioralpolicy.org/what-is-nudging/

[Accessed 4 September 2020].

Hartmann,

C. and Siegrist, M., 2017. Consumer perception and behaviour regarding

sustainable protein consumption: a systematic review. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 61, pp.11-25.

Hedin,

B., Katzeff, C., Eriksson, E. and Pargman, D., 2019. A systematic review of

digital behaviour change interventions for more sustainable food consumption. Sustainability, 11(9),

pp.1-23.

Helmefalk,

M. and Berndt, A., 2018. Shedding light on the use of single and multisensory

cues and their effect on consumer behaviours. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag, 46, pp.1077-1091.

Henderson,

S., Nink, E., Nierenberg, D. and Oakley, E., 2015. The real cost of food: examining the social, environmental and

health impacts of producing food, Baltimore:

Food Tank.

Hollands,

G. et al., 2017. The TIPPME intervention typology for changing environments to

change behaviour. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(0140), pp.1-14.

Holloway,

T., Salter, A. and McCullough, F., 2012. Dietary intervention to reduce meat

intake by 50% in university students – a pilot study. Proc. Nutr. Soc, 71,

p.164.

Just,

D. R. and Wansink, B., 2009. Smarter lunchrooms: using behavioral economics to

improve meal selection. Choices, 24(3), pp.1-7.

Kácha,

O. and Ruggeri, K., 2019. Nudging intrinsic motivation in environmental risk

and social policy. Journal of Risk Research, 22(5), pp.581-592.

Kahneman,

D., 2011. Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kaljonen,

M., Salo, M., Lyytimaki, J. and Furman, E., 2020. From isolated labels and

nudges to sustained tinkering: assessing long-term changes in sustainable

eating at a lunch restaurant. British Food Journal, 122(11), pp.1-17.

Kasperbauer,

T., 2017. The permissibility of nudging for sustainable energy consumption. Energy Policy, 111,

pp.52-57.

Kearney,

J., 2010. Food consumption trends and drivers. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. B, 365, pp.2793-2807.

Kerr,

J. and Foster, L., 2011. Sustainable consumption – UK Government activity. Nutrition Bulletin, 36,

pp.422-425.

Ketelsen,

M., Janssen, M. and Hamm, U., 2020. Consumers’ response to

environmentally-friendly food packaging – a systematic review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 254, pp.120-123.

Kraak,

V., Englund, T., Misyak, S. and Serrano, E., 2017. A novel marketing mix and

choice architecture framework to nudge restaurant customers toward healthy food

environments to reduce obesity in the United States. Obesity Reviews, 18,

pp.852-868.

Kurz,

V., 2018. Nudging to reduce meat consumption: immediate and persistent effects

of an intervention at a university restaurant. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 90, pp.317-341.

Lassalette

et al., 2014. Food and feed trade as a driver in the global nitrogen cycle:

50-year trends. Biogeochemistry, 118, pp.225-241.

Lea,

E., Crawford, D. and Worsley, A., 2006. Public views of the benefits and the

barriers to the consumption of a plant-based diet. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 60, pp.828-837.

Lehner,

M., Mont, O. and Heiskanen, E., 2016. Nudging – a promising tool for

sustainable consumption behaviour?. Journal of Cleaner Production, 134(A), pp.166-177.

Liu,

J., Thomas, J. and Higgs, S., 2019. The relationship between social identity,

descriptive social norms and eating intentions and behaviors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 82, pp.217-230.

Löfgren,

Å., Martinsson, P., Hennlock, M. and Sterner, T., 2012. Are experienced people

affected by a pre-set default option – results from a field experiment. Journal of Environmental Economics,

63(1), pp.66-72

Lombardini,

C. and Lankoski, L., 2013. Forced choice restriction in promoting sustainable

food consumption: Intended and unintended effects of the mandatory vegetarian

day inHelsinki schools. J. Consum. Policy, 36, pp.159-178.

Loschelder,

D. D., Siepelmeyer, H., Fischer, D. and Rubele, J. A., 2019. Dynamic norms

drive sustainable consumption: Norm-based nudging helps café customers to avoid

disposable to-go-cups. Journal of Economic Psychology, 75(A). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2019.02.002

Marteau,

T., 2017. Towards environmentally sustainable human behaviour: targeting

non-conscious and conscious processes for effective and acceptable policies. Phil. Trans. R. Soc A, 375. https://doi: 10.1098/rsta.2016.0371

Masicampo,

E. and Baumeister, R., 2008. Toward a physiology of dual−process reasoning and

judgment: lemonade, willpower, and expensive rule−based analysis. Psychol. Sci, 19,

pp.255-260.

McBey,

D., Watts, D. and Johnstone, A. M., 2019. Nudging, formulating new products,

and the lifecourse: a qualitative assessment of the viability of three methods

for reducing Scottish meat consumption for health, ethical, and environmental

reasons. Appetite, 142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.104349

McDaniel,

J. H., Hunt, A., Hackes, B. and Pope, J. F., 2001. Impact of dining room

environment on nutritional intake of Alzheimer’s residents: a case study. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 16(5), pp.297-302.

McDonald,

R. I., Fielding, K. S. and Louis, W. R., 2014. Conflicting norms highlight the

need for action. Environment and Behavior, 46, pp.139-162.

Morizet,

D. et al., 2012. Effect of labeling on new vegetable dish. Appetite, 59,

pp.399-402.

Nørnberg,

T. R., Houlby, L., Skov, L. R. and Peréz-Cueto, F. J. A., 2015. Choice

architecture interventions for increased vegetable intake and behaviour change

in a school setting: a systematic review. Perspectives in Public Health, 136(3), pp.132-142.

Notarnicola

et al., 2017. Environmental impacts of food consumption in Europe. Journal of Cleaner Production, 140, pp.753-765.

Ohlhausen,

P. and Langen, N., 2020. When a combination of nudges decreases sustainable

food choices out of home – the example of food decoys and descriptive name

labels. Foods, 9(557), pp.1-18.

Peričić-Poklepović,

T. and Tanveer, S., 2019. Why systematic reviews matter, [online]

Available at: https://www.elsevier.com/connect/authors-update/why-systematic-reviews-matter [Accessed 26 August 2020].

Piester,

H. E. et al., 2020. “I’ll try the veggie burger”: increasing purchases of

sustainable foods with information about sustainability and taste. Appetite, 155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104842

Ratner,

R. K. et al., 2008. How behavioral decision research can enhance consumer

welfare: From freedom of choice to paternalistic intervention. Marketing Letters, 19, pp.383-397.

Rausch,

T. and Kopplin, C., 2021. Bridge the gap: consumers’ purchase intention and

behavior regarding sustainable clothing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123882

Ritchie,

H. and Roser, M., 2020. Environmental impacts of food

production, [online]

Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/environmental-impacts-of-food

[Accessed 25 August 2020].

Salmivaara,

L. and Lankoski, L., 2019. Promoting sustainable consumer behaviour through the

activation of injunctive social norms: a field experiment in 19 workplace

restaurants. Organization and Environment, DOI: 10.1177/1086026619831651

Scarborough,

P. e. a., 2014. Dietary greenhouse gas emissions of meat-eaters, fish-eaters,

vegetarians and vegans in the UK. Climate Change, 125, pp.179-192.

Schanes,

K., Dobernig, K. and Goezet, B., 2018. Food waste matters – a systematic review

of household food waste practices and their policy implications. Journal Of Cleaner Production, 182, pp.978-991.

Schoesler,

H., de Boer, J. and Boersema, J., 2014. Fostering more sustainable food

choices: can Self-Determination Theory help?. Food Quality And Preference, 35, pp. 9-69.

SCORAI,

2018. Third international conference

of the sustainable consumption research and action initiative, [online] Available at: https://scorai.net/2018conference/

[Accessed 4 September 2020].

Shiv,

B. and Fedorikhin, A., 1999. Heart and mind in conflict: the interplay of

affect and cognition in consumer decision-making. Journal of Consumer Research, 26, pp.278-292.

Simonson,

I., 1989. Choice based on reasons: the case of attraction and compromise effects. J. Consum, Res, 16,

pp.158-174.

Slapø,

H. B. and Karevold, K. I., 2019. Simple eco-labels to nudge customers toward

the most environmentally friendly warm dishes: an empirical study in a

cafeteria setting. Frontiers in Sustainable Food

Systems, 3(40),

pp.1-9.

Sunstein,

C., 2013. Behavioural Economics, Consumption, and Environmental Protection. In:

L. Reisch and J. Thøgersen, eds. 2013. Handbook on research in

sustainable consumption. pp.1-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2296015

Sustainable

Food Trust, 2019. The hidden cost of UK food. Bristol: Sustainable Food Trust.

Taghikhah,

F., Voinov, A. and Shukla, N., 2019. Extending the supply chain to address

sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 229, pp.652-666.

Taufika,

D., Verain, M., Bouwman, E. and Reinders, M., 2019. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 93, pp.281-303.

Thaler,

R. and Sunstein, C., 2008. Nudge: improving decisions

about health, wealth, and happiness. London: Penguin Books.

Thorndike,

A. N., Riis, J., Sonnenberg, L. M. and Levy, D. E., 2014. Traffic-light labels

and choice architecture: promoting healthy food choices. Am. J. Prevent. Med, 46,

pp.143-149.

Tillman,

D. and Clark, M., 2014. Global diets link environmental sustainability and

human health. Nature, 515, pp.518-522.

Torma,

G., Aschemann-Witzel, J. and Thøgersen, J., 2018. I nudge myself: exploring

‘self-nudging’ strategies to drive sustainable consumption behaviour. Int J Consum Stud, 42, pp.141-154.

UNCED,

1992. Agenda 21: sustainable

development knowledge platform. [Online]

Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf

[Accessed 4 September 2020].

United

Nations, 2020. Sustainable consumption and

production: United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, [online] Available at:https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/

[Accessed 25 August 2020].

Van

Doorn, J. and Verhoef, P., 2011. Willingness to pay for organic products:

differences between virtue and vice foods. Int. J. Res. Mark, 28(3),

pp.167-180.

Van

Kleef, E., Otten, K. and Van Trijp, H., 2012. Healthy snacks at the checkout

counter: a lab and field study on the impact of shelf arrangement and

assortment structure on consumer choices. BMC Public Health, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-1072

Vandenbroele,

J., Slabbinck, H., Van Kerckhove, A. and Vermeir, I., 2018. Curbing portion

size effects by adding smaller portions at the point of purchase. Food Quality and Preference, 64, pp.82-87.

Vandenbroele,

J. et al., 2019. Nudging to get our food choices on a sustainable track. Proceedings of The Nutrition Society, 79(1), pp.1-14.

Vecchio,

R. and Cavallo, C., 2019. Increasing healthy food choices through nudges: a

systematic review. Food Quality and Preference, 78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.05.014

Vermeer,

W. M., Steenhuis, I. H. and Seidell, J. C., 2010. Portion size: a qualitative

study of consumers’ attitudes toward point-of-purchase interventions aimed at

portion size. Health Education Research, 25, pp.109-120.

Viegas,

C. andLins, A., 2019. Changing the food for the future: food and

sustainability. European Journal Of Tourism

Hospitality And Recreation, 9(2),

pp.52-57.

Wansink,

B., 2015. Change their choice! changing behavior using the CAN approach and

activism research. Psychology and Marketing, 32(5), pp.486-500.

White,

K., Habib, R. and Hardisty, D., 2019. How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be

more sustainable: a literature review and guiding framework. Journal of Marketing, 8(3), pp.22-49.

Wilson,

A., Buckley, E., Buckley, J. and Bogomolova, S., 2016. Nudging healthier food

and beverage choices through salience and priming. Evidence from a systematic

review. Food Qual. Prefer, 51, pp.47-64.

Worsley,

A., Wang, W. C. and Farragher, T., 2016. The associations of vegetable

consumption with food mavenism, personal values, food knowledge and demographic

factors. Appetite, 97, pp.29-36.

Zakowska-Biemans,

S., Pieniak, Z., Kostyra, E. and Gutkowska, K., 2019. Searching for a measure

integrating sustainable and healthy eating behaviors. Nutrients, 11(95),

pp.1-17.

Zhou,

X. et al., 2019. Promotion of novel plant-based dishes among older consumers

using the ‘dish of the day’ as a nudging strategy in 4 EU countries. Food Quality and Preference, 75, pp.260-272.