Post-materialism as a basis for achieving

environmental sustainability

First online: 20 July 2021

Douglas

E. Booth

Associate

Professor Retired, Marquette University

cominggoodboom@gmail.com

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

DOI: 10.3197/jps.2021.5.2.97

Licensing: This article is Open Access (CC BY 4.0).

How to Cite:

Booth, D. 2021. 'Post-materialism as a basis for achieving environmental sustainability'. The Journal of Population and Sustainability 5(2): 97–125.

https://doi.org/10.3197/jps.2021.5.2.97

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Abstract

A recent article in this

journal, “Achieving a Post-Growth Green Economy”, argued that a turn to

post-material values by younger generations may be setting the stage for a more

environmentally friendly, post-growth green global economy. To expand the foundations

for the possible emergence of such an economy, the current article offers

empirical evidence from the World Values Survey for the propositions that

individual post-material values and experiences leads to (1) a reduction in

consumption-oriented activities, (2) a shift to more environmentally friendly

forms of life that include living at higher, more energy efficient urban

densities, (3) having families with fewer children, and (4) greater political

support for environmental improvement. Such behavioral shifts provide a

foundation for a no-growth, or even a negative-growth, economy among the

affluent nations of the world leading to declining rates of energy and

materials throughput to the benefit of a healthier global biosphere.

Keywords:

post-materialism; sustainability; population growth; post-growth economy

Introduction

A

sea-change in values among middle-class youth has occurred around the world

away from giving high social priority to materialist economic social goals and

towards non-economic social purposes such as advancing freedom of expression

and increasing social tolerance (Inglehart, 2008; Norris and Inglehart, 2019).

This change appears to be accompanied by less emphasis on the pursuit of wealth

and material possessions and more emphasis on seeking cultural and social

experiences that take place outside the sphere of economic transactions or

within the economic arena but for non-economic purposes. This article

hypothesizes that such a shift in outlook and activities brings a less entropic

and more environmentally friendly way of living and greater political support

for sustaining a healthy natural environment. Not only have values shifted in a

post-material direction away from more traditional concerns among global

populations, but interest in the pursuit of post-material experiences beyond

the strictly economic has expanded as well. In the following, data from the

World Values Survey, Wave 6 (2010-2014) will be used to offer evidence for

these claims and to show that post-materialists are (1) less oriented to

expanding material consumption, (2) choose to reside in denser, more energy

efficient urban settings, (3) have smaller families than others, and (4)

support the environment through political actions, all to the benefit of a

healthier global biosphere (World Values Survey Association, 2015).

Various

authors have suggested limiting material economic activity in those countries

most responsible for the violation of ecological sustainability measures such

as the ecological, carbon, or materials consumption footprints. Some argue

simply for a cessation of economic growth and others for actual reductions in

economic activity in order to meet global sustainability goals (Booth, 2020a;

Jackson, 2017, 2019; Victor, 2008). To accomplish either of these would

be a profound political act and require a substantial constituency. Such a

constituency is potentially found amongst individuals who express post-material

values or participate in post-material experiences. These individuals are more

likely than others to themselves limit their material consumption and to be

strongly supportive of doing something about global environmental problems.

Whatever position taken on the question of limiting growth to address harms to

the environment, the historical evidence is clear that economic growth, and the

technological changes and population expansion behind it, have brought about

substantial harms to the environment, and this is especially the case for the

U.S. and the U.K. (Booth, 1998).

The post-material silent revolution

Ronald

Inglehart and his colleagues have extensively documented a ‘silent revolution’

in social values among younger generations occurring over the last half of the

20th Century and continuing into the early 21st Century

(Inglehart, 1971, 2008; Inglehart and Abramson, 1994). In these years, the

‘silent revolution’ in the formation of post-material values made significant

advances in the world’s most affluent countries, which have gained the

capability of providing economic and physical security to younger generations

as they come of age (Inglehart, 1971; Inglehart and Welzel, 2005; Norris and

Inglehart, 2019). Statistical evidence shows a substantial advance in the ratio

of post-materialist to materialist values in a diverse collection of European

countries and the U.S. (Inglehart, 2008; Inglehart and Norris, 2016). Growing

up in economically secure conditions enables the formation of ‘liberal’

post-material values among younger generations such as freedom of expression,

social tolerance of all irrespective of race or sexual predilections, a humane

society based on ideas rather than money, and democracy in all of life’s

arenas. These values are given disproportionate support by younger individuals

over such materialist goals as increased economic growth and expanded personal

security (Inglehart, 2008; Inglehart and Abramson, 1999). Inglehart also

provides evidence showing that younger generations continue to be more

post-materialist than older generations over time despite fluctuations in

post-materialism measures related to economic cycles (Inglehart, 2008). In

brief, as particular generations age they retain their basic commitment to

values formed in their younger years.

The

realization of post-material values more commonly occurs among those from more

affluent middle-class backgrounds than among those from less economically

secure working-class backgrounds (Inglehart and Abramson, 1994, 1999; Inglehart

and Welzel, 2005). For this reason, a class divide between middle-class

post-materialists and working-class materialists who occupy the lower end of

the social class spectrum is likely (Booth, 2020b).

The World Values Survey data

and measuring post-materialism

The

data source used in the following analysis comes from the World Values Survey,

Wave 6, a global sample survey of a full array of human values under the

auspices of the World Values Survey Association composed of 100-member

countries (World Values Survey Association, 2015). For a full explanation of

the methodology behind the survey, go to the World Values Survey web site,

http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org. The survey is funded by member countries and

a variety of foundations and administered in person to a randomly selected set

of respondents by professional staff and is confined to adults 18 and older. Wave

6 data were collected over the period from 2010 to 2014 and include 60

countries (Table A1) and a total sample of 86,274 respondents.

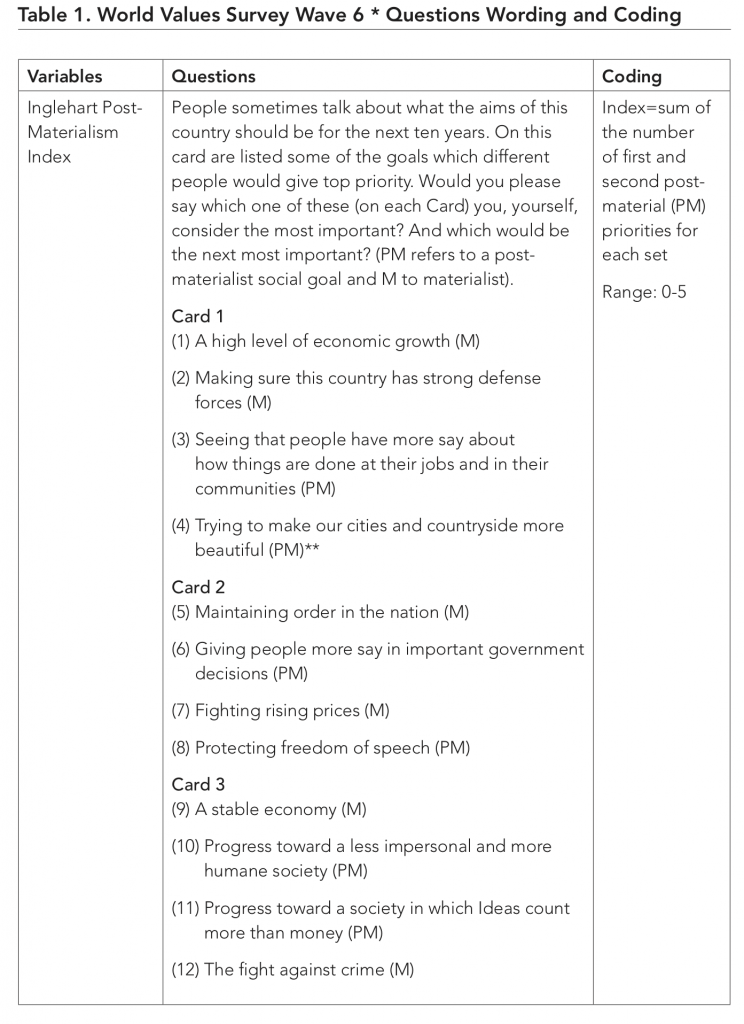

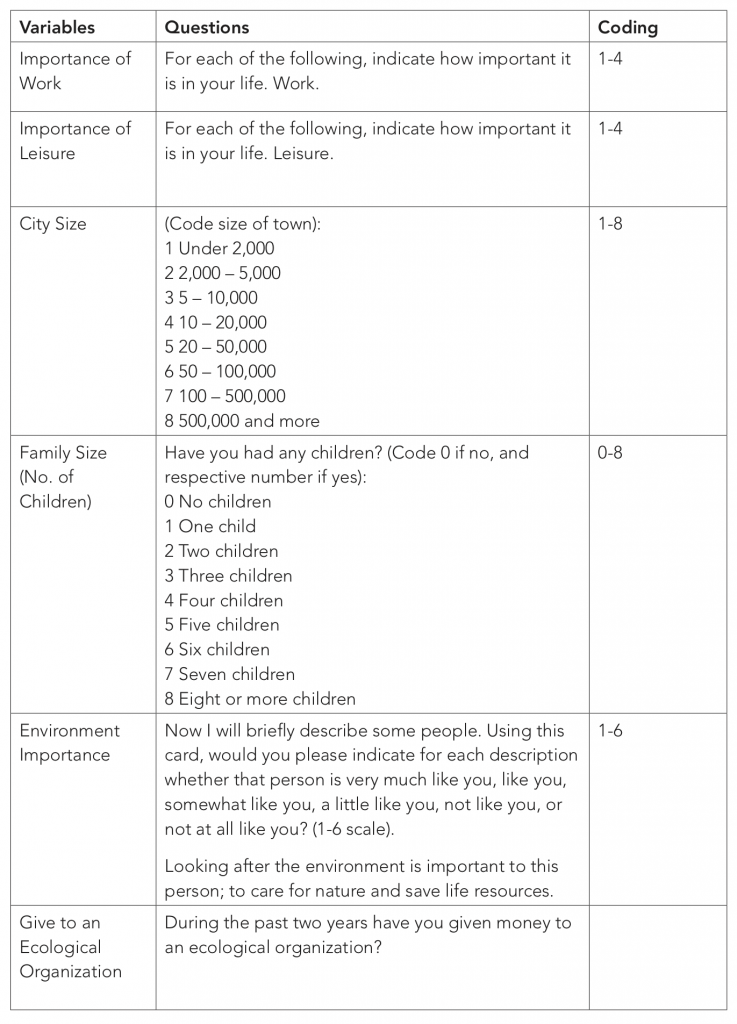

A

post-materialism index based on respondent expressions of attitudes towards

materialist and post-materialist social goals can be constructed using data

from the World Values Survey-Wave 6 (WVS), administered over the period

2010-2014 (World Values Survey Association, 2015), and is referred to here as

the Inglehart post-materialism index. The construction of the index is set out

in Table 1 where all WVS variables used in the following are described. Data

from the WVS survey shows that 69 % of respondents are materialists who each

claim less than a majority of post-material social goals among the options used

in the construction of the Inglehart Post-Materialism Index, and 31 % are

post-materialists who each claim a majority of their social goals as

post-material (World Values Survey Association, 2015). Between the WVS wave 6

(2010-2014) and wave 7 (2017-2020), for 32 countries common to each sample, the

share of post-materialists increased more than 10 % from 30.5 to 33.7 % of the

global sample population (World Values Survey Association, 2015, 2020).

Unsurprisingly, in an outwardly materialist world, post-materialists still

constitute a minority of the population, but one that has expanded in recent

decades in European countries and the U.S. as already described (Norris and

Inglehart, 2019).

The

formation of post-material values has also resulted in the advance of

post-material experiences such as joining voluntary groups, pursuing creativity

and independence in the world of work, and engaging in political actions,

experiences that go beyond a strict focus on accumulating financial wealth and

material possessions (Booth, 2018a, 2020b). Henceforth in this article, the

terms ‘post-materialism’ and ‘post-materialist’ will encompass both Inglehart

post-material values and post-material experiences. If we are materialists, our

life’s focus is on gaining control over both tangible and material-like

intangible objects and transforming them to mirror our deepest wishes (Booth,

2018a). Our experience of such control and its resulting manipulations of the

material stuff of life is sensual and virtual, a product of our

perception-driven, conscious thought process. Our desire to physically

manipulate and alter objects as we find them in nature can ultimately result in

huge transformations of the material world. Witness the remaking of the global

environment following, first, the agricultural revolution and, second, the

industrial revolution (Harari, 2015).

Some

object ownership is inevitably a part of all our lives—we each need our own

private supply of food, clothing, living space, and such—but post-materialists

look increasingly for experiences and actions not necessarily contingent on

ownership of objects in their field of perception. For post-materialists, the

essential quest in life is for experiences of the world apart from any

requirements for ownership and private control. A post-materialist is not just

someone with a certain value orientation, but a person who lives in a certain

way and participates in certain kinds of activities. A post-materialist can

afford to pursue extensive activities beyond the purely economic. Three

activities of this kind postulated here are these: (1) voluntary group membership,

(2) creative and independent work such as that undertaken by artists, and (3)

political action beyond voting in support of some cause. Each measures a

dimension of post-material, action-oriented experience where private

possessions or wealth are secondary and, in some cases, inessential to the

activity (Booth, 2018a). The World Values Survey (WVS) can be utilized to

construct measures of these activities and estimate the extent of participation

in them (World Values Survey Association, 2015). An index of voluntary group

membership can be formulated from WVS inquiries about respondent participation

in (a) sport or recreational, (b) art, music, or educational, (c)

environmental, or (d) humanitarian or charitable organizations with inactive

membership assigned a value of 1 and active membership a value of 2 for each of

the four organizational categories which are then added up for each survey

respondent (Table 1). These organizations were chosen on the assumption that

participation in each type generally requires only a modest amount of material

possessions or financial wealth. The particular kind of groups selected here

are those that normally provide a public benefit of some kind and would

consequently be of interest to individuals with post-material values seeking

self-expressive activities. People choose to belong to other kinds of

organizations including labor unions, political organizations, and professional

groups, but these generally have a ‘utilitarian’ focus and provide private

benefits of some kind to members. Membership in utilitarian groups was

virtually flat globally between 1980 and 2000 in post-industrial societies, but

by contrast public benefit groups experienced substantial growth (Welzel,

Inglehart, and Deutsch, 2005).

The

extent of creative and independent tasks at work can be measured by summing up

two WVS survey responses, each measured on a 1-10 scale, first, that asks

whether work tasks are mostly routine or mostly creative and, second, whether

independence is exercised in performing work tasks (Table 1). Seeking work that

possesses such characteristics doesn’t necessary require one to be materially

wealthy, as in the case of so-called ‘starving artists’ (Alper and Wassall,

2006; Lloyd, 2002). Work does necessitate participation in a product market for

the self-employed or a labor market and is inevitably subject to market

transactions unlike membership in voluntary organizations or participation in

political action, but product or labor market income can often be traded off

for creative and independent tasks (Alper and Wassall, 2006).

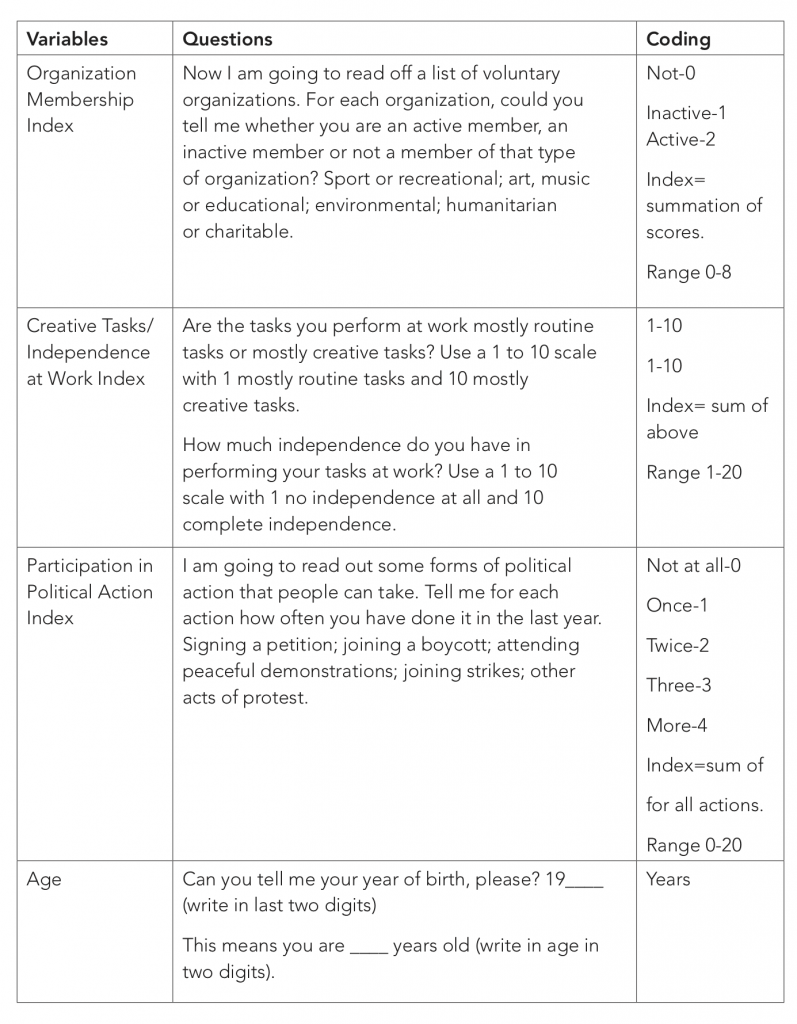

Participation

in political action can be measured with the sum of the number of times (up to

a maximum of four each) that a respondent signed a petition, joined a boycott,

attended a peaceful demonstration, joined a strike, or participated in some

other act of protest (Table 1). Participation in such activities normally

doesn’t require much in the way of material possessions and financial wealth.

Actions of this kind are the product of either formal or informal mass

organization by activists and can frequently be described as

‘elite-challenging’. Such actions experienced an upswing in the last two

decades of the 20th Century in post-industrial societies

(Inglehart and Welzel, 2005; Welzel et al., 2005).

The

three experience activities should measure phenomenon significant in daily life

if these phenomena are to be of any importance. The World Values Survey—Wave 6

(WVS) data reveal that voluntary organizations indeed matter for respondents,

33.5 % of whom belonged to at least one athletic, arts, environmental, or

humanitarian organization. For membership scoring purposes, inactive membership

in each type of organization is given a value of 1, and active membership a

value of two. Of those who participate in on or more of the four types of

voluntary organizations, the mean participation score is 2.81 out of a maximum

possible of 8, the latter number being achieved only with active membership in

all four types of organizations. The mean sample score for creative and

independent tasks is 10.5 out of a possible 20 with approximately 23 % of the

sample realizing a score of 15 or more, suggesting that creativity and

independence in work occurs for a substantial portion of the respondent working

population. Finally, the rate of respondent participation in political action

is 20.4 % of the total sample population and the mean participation rate is 3.0

actions for those who are politically active. The three experience activities

are thus a significant part of individual lives on a global scale, and

importance of post-material experiences around the world is established for a

substantial minority of the sample population (Booth, 2018a).

The statistical approach

To

repeat, the purpose of the statistical analysis to follow will be to provide

evidence that (1) post-materialists are less oriented than materialists to

expanding material consumption; (2) choose more so than others to reside in

denser, more energy efficient urban settings; (3) have smaller families than

others; and (4) support the environment through political actions, all to the

benefit of a healthier global biosphere. The basic statistical approach is to

use regression analysis to show that post-materialism measures are statistical

predictors of (1) – (4) in a global setting. Using such a large survey with

such a diverse geographic coverage for this task has its benefits and dangers.

The benefit is that the statistical results apply globally. The drawback is

that any useful regression analysis for such a large sample will necessarily

leave out a huge number of possible explanatory variables and will end up

explaining a relatively small portion of variation in the data. Nonetheless,

with such an analysis significant statistical relations can be discovered that

are highly useful in explaining human behavior. To account for country-level

differences, a hierarchical mixed-effects regression technique is used that

creates a random effects constant for each country that controls for country

differences unaccounted for by included variables in regressions equations

(Stata Corporation, 2015). Note that actual sample sizes will be reduced in

equations limited to the actively employed portion of the sample and generally

because of missing data where respondents fail to answer questions.

Statistical analysis of

post-materialism

The

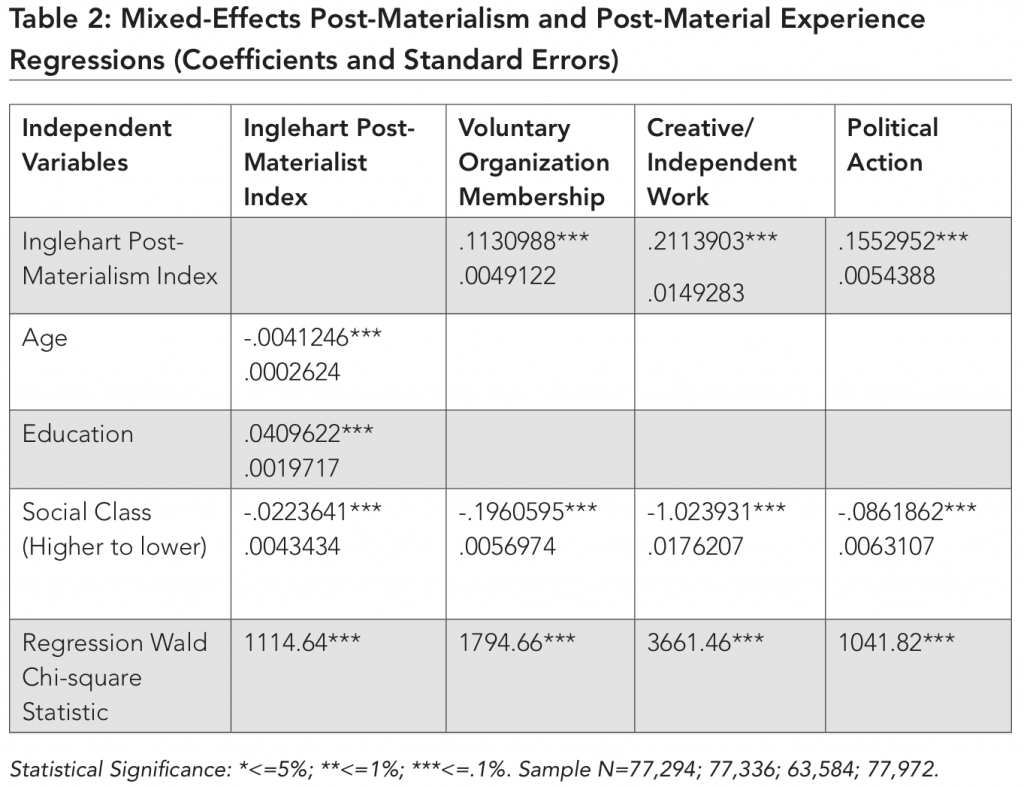

following WVS regressions (Table 2) confirm that (1) Inglehart Post-Materialism

is predicted negatively by age and positively by education, (2) the three

post-material experiences—Voluntary Organization Membership, Creative and

Independent Work, and Political Action—are in turn positively predicted by

Inglehart Post-Materialism, and (3) Social Class (higher to lower) negatively

predicts both Post-Materialism and post-material experiences:

Younger

individuals tend to be more post-materialist than their older peers and

education positively predicts the post-materialism index as Inglehart’s theory

postulates. Education is both a liberalizing force and an indicator of an

economically secure upbringing (Inglehart and Welzel, 2005 p. 37).

Post-material values matter in choosing to engage in post-material experiences

as inferred by the post-materialism index positively predicting each of the

post-material experiences. This analysis makes clear that social class

(measured higher to lower) also matters for both post-material values and

experiences and has a negative impact on respondent post-materialism, meaning

that members of the working class are more heavily materialist in their outlook

than the middle and upper classes and are also less likely to participate in

post-material experiences.

The

emergence of post-materialism is especially interesting because it is

intrinsically ‘anti-capitalist’ in its value-orientation and its conversion to

a focus on actions and activities beyond the realm of marketed material

possessions. The post-materialist movement according to Inglehart and

Welzel is ‘elite-challenging’, and it supports an expansion of democracy in all

of life’s arenas including the workplace, something that would be antithetical

to the bureaucratic form of control exercised within the modern capitalist

corporation (Welzel et al., 2005). Carried to its logical conclusion, a

switch to post-material values and experiences means a dampening of demand

growth for consumer goods without which modern capitalism loses an essential

driver for its expanding global influence. Were post-materialism to become

globally prevalent and a threshold income reached universally beyond which

demand for further material possessions takes a back seat to post-material

experiences, then global growth in consumer demand could well shrink towards

zero. Historically, the central opposing force to unfettered capitalism has

been the materialist-oriented labor movement driven by the tendency of large

corporations in the pursuit of profits to place downward pressure on wages and

upward pressure on labor effort. Materialist members of the working class and middle-class

post-materialists both have interests counter to the unhindered operation of

capitalist enterprises, but these interests differ. Workers primarily desire

increased incomes and economic security through higher wages and benefits that

as a cost of production eat into business profits, and post-materialists are

more oriented to obtaining increases in freedom of expression, expanded say

over the organization of the work process, and the enlargement of life

prospects beyond market transactions. This division is important and will be

revisited later in this article. For now, it is worth noting that while their

interests differ, both post-materialists and the working-class individuals in

the pursuit of their particular interests oppose key outcomes delivered by

capitalist businesses.

Post-materialism as a

low-entropy form of life

The

future spreading of a ‘post-material silent revolution’ around the world, I

will now argue, provides an economic and political foundation for an

environmentally friendly ‘green economy’ with less energy and materials

throughput and associated waste emissions, an outcome that may well be

essential to prevent the existential threat of climate change and other

environmental stresses to the global biosphere. To repeat, the ‘silent

revolution’ will assist in bringing about such an economy for the following

reasons: (1) first and foremost, post-materialists likely consume relatively

less over their life-time than materialists with similar economic

opportunities, reducing the negative effects of such consumption on the

environment; (2) post-material forms of living and experiences tend to be less

entropic and harmful to the environment than materialist ways of life; (3)

post-materialists have smaller families dampening global fertility and

eventually population growth and associated environmental harms; (4) and

post-materialists are more supportive of environmental protection than others

in both their attitudes and political actions, increasing the likelihood of

government action favorable to the environment.

Those

who adopt a post-material way of life are more prone than others to lack an

interest in accumulating material possessions beyond a basic threshold level.

As already described, post-material experiences tend to be pursued for their

own sake, and material possessions are wanted for their supporting role in

meeting the basic threshold material requirements of modern life. This infers

that beyond some point post-materialists will be uninterested in voluntarily

expanding either their consumer purchases or their purchasing power. In such

circumstances, added economic growth is no longer desired, especially if it

means more working hours and less time for post-material experiences. Simply

put, the spread of post-materialism carries with it an attendant dampening of

growth in consumer demand that in turn will diminish the growth of aggregate

economic demand and output measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In brief,

more post-materialism, less economic growth, lower energy and materials

throughput and reduced waste emissions, and the closer a country comes to the

reality of an environment-conserving ‘green economy’.

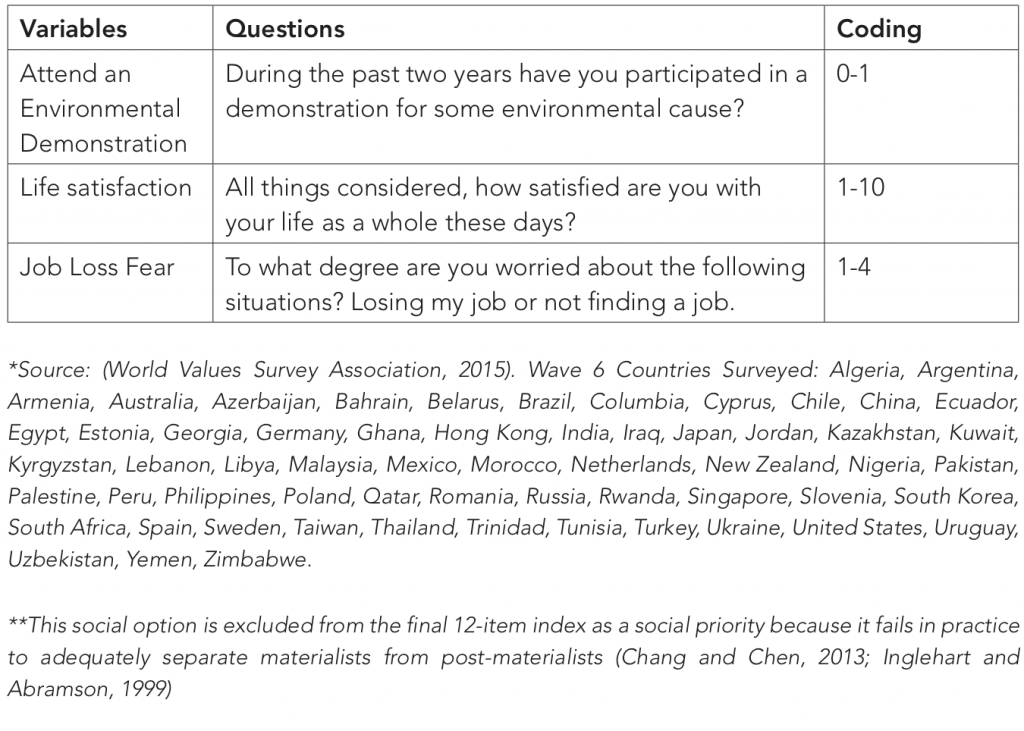

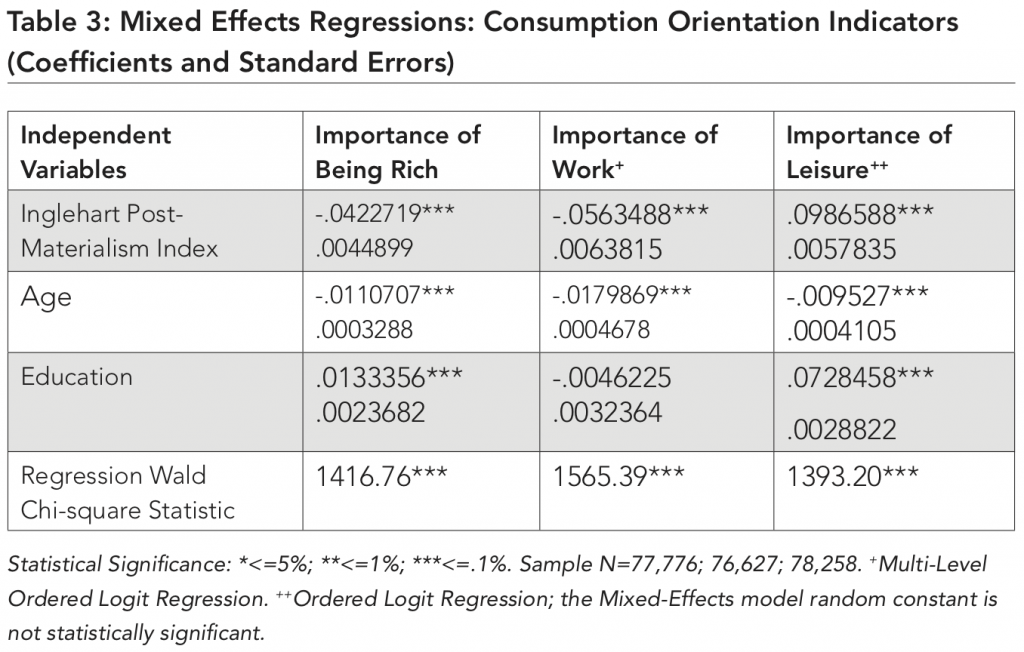

The

evidence for reduced consumption by post-materialist is circumstantial given

the unavailability of actual data on consumption for those who profess

post-material values, and such evidence is available from the World Values

Survey (WVS). That survey asks three different questions that shed light on an

individual’s commitment to earning and spending on consumer goods (see Table

1): (1) How important is it to the respondent ‘to be rich’ and have a lot of

money and expensive things (1-6 scale), (2) How important is ‘work’ in the

respondent’s life (1-4 scale), and (3) How important is ‘leisure’ in the

respondent’s life (1-4) scale. Statistical analysis of the WVS data in Table 3

on these questions finds that the Inglehart Post-Materialism Index is a

significant negative predictor of the Importance of Being Rich and the

Importance of Work and a positive predictor of the Importance of Leisure

controlling for Age and Education:

In

other words, post-materialists express a positive desire for leisure but a

negative desire for being rich and engaging in work, the latter two being

positive indicators of a materialist consumption orientation, and leisure being

important to the pursuit of post-material experiences as a substitute for

seeking more income to fund expanded material consumption.

Having

attained a basic threshold of economic security and material possessions,

post-materialists not only limit their overall demand for material possessions,

but as a matter of taste seek a comparatively low-entropy form of life, placing

less demand on energy and materials flows to the benefit of the environment.

Post-materialists are more prone than others to reside in larger, denser cities

that are more energy efficient and thus less entropic than the spread-out

suburban areas so attractive to their older peers after World War II (Booth, 2018b).

Energy efficiency increases with urban density for such reasons as reduced

human travel distances, less use of energy inefficient private motor vehicles

and more use of energy efficient public transit, and lower per person

consumption of private dwelling space and associated heating and cooling energy

requirements (New York City, 2007; Newman and Kenworthy, 1999, 2015). In

the U.S., a return to downtown living has been driven in part by Millennials

choosing to live in high-density urban neighborhoods as opposed to spread out

low-density suburbs (Birch, 2005, 2009). Even in already densely populated

countries such as Germany, center-city, dense neighborhoods recently

experienced a relative surge in population growth driven by younger generations

(Brombach, Jessen, Siedentop, and Zakrzewski, 2017). Complementary to

higher-density living by younger generations in the USA, the rate of car

ownership and the miles of driving undertaken by Millennials is less than their

older peers (Polzin, Chu, and Godrey, 2014). Higher urban densities support

more of the publicly shared experience opportunities afforded by parks,

libraries, public squares, museums, art galleries, entertainment and sports

venues, spaces for group meetings and public demonstrations, street cafes, and

more that provide opportunities for a post-material mode of living (Markusen,

2006; Markusen and Gadwa, 2010; Markusen and Schrock, 2006).

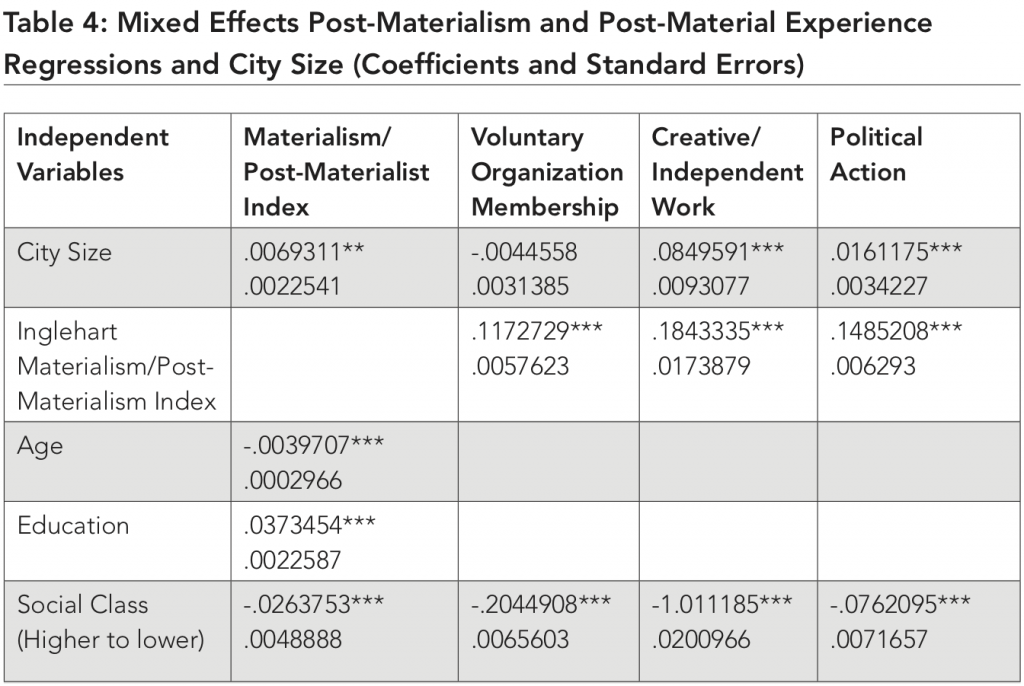

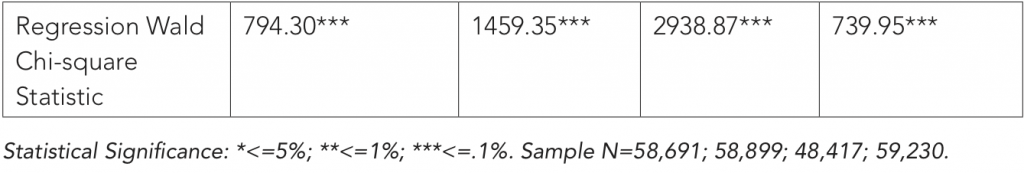

Data

in the latest World Values Survey (WVS) confirms that Inglehart

post-materialists and those who engage in two of three post-material

experiences—creative and independent work and political action—tend to reside

in larger cities around the world controlling for individual respondent Age,

Education, and Social Class (Table 4):

This

is an especially important inclination because, larger cities feature greater

residential density, and, as already described, denser cities are more energy

efficient, less entropic places to live (Newman and Kenworthy, 1999, 2015;

Tsai, 2005). City Size is a statistically significant predictor in the

Post-materialism, Creative/Independent Work, and the Political Action

equations. The only exception occurs in the Voluntary Organization Membership

equation where City Size lacks statistical significance. Organization

Membership is apparently invariant with respect to city size.

Simply

put, the choices made by post-materialists about where and how to live lead

them to a less entropic and environmentally destructive form of life, and this

is on top of their inclination to lower aggregate rates of material

consumption.

A

third choice that post-materialist make favorable to a slow-growth green

economy is to have fewer children, placing downward pressure on human fertility

and ultimately population growth. Global economic growth as measured by GDP

contains two components: (1) growth in GDP per capita, and (2) growth in global

population (Booth, 2020a; Jackson, 2019). The turn to post-materialism and its

focus on purposes and activities outside the economic arena serves to dampen

growth in GDP per capita as already suggested. Choosing to live in higher

density settings, in and of itself, limits the accumulation of material

possessions—less space, less stuff. Less population growth will mean less

growth in GDP as well. The rate of human fertility that drives global

population growth is, thankfully, declining at a fairly rapid rate, although it

still has some distance to go to reach the magic 2.1 (children born per women)

that will lead to long run population stability. Globally, world fertility

peaked at 5.06 in 1964 and declined to 2.43 in 2017. The fertility rates for

lower-middle, upper-middle, and high-income countries are respectively 2.3,

1.9, and 1.6, suggesting that population stability, and in some countries even

population decline, is on the horizon (World Bank, 2019a). The global

population annual growth rate peaked in 1969 at 2.11 % and declined to 1.11 %

in 2018 (World Bank, 2019b).

There

is an abundant literature on human fertility explaining the reasons for its

decline, and increased individual family affluence, education, and access to

health care are among the most important causes, each of which was in turn

rendered possible in the past by economic growth per capita (Rogers and

Stephenson, 2018). While historically the turn to post-materialism is certainly

a modest contributor to the aggregate decline in fertility, the simple point to

be made here is that post-materialists indeed contribute to fertility decline

and will likely continue to do so in the future by possessing lower fertility

rates than their materialist peers according to data in the WVS data analysis

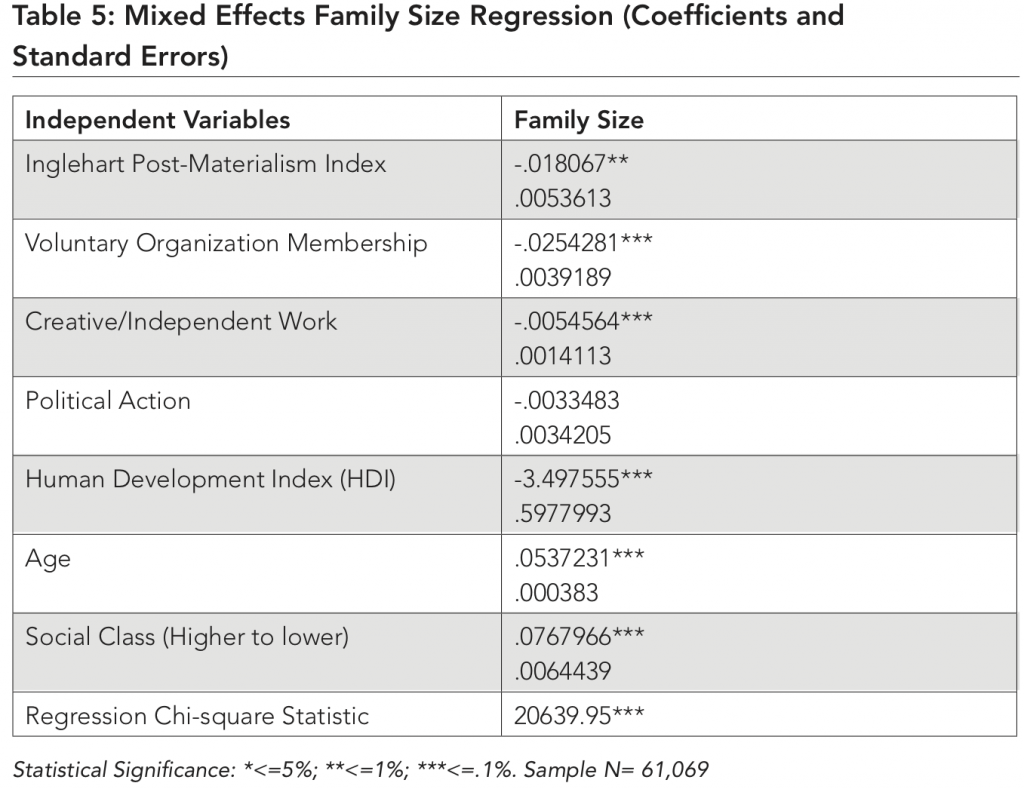

in Table 5:

Post-Materialism

and two measures of post-material experience—Voluntary Organization Membership

and Creative and Independent Work—are statistically significant ‘negative’

predictors of Family Size controlling for respondent Age. Inglehart

post-materialists and those who participate in two out of three post-material

experiences thus have smaller families with fewer children than others. A

comprehensive and widely used measure of economic and social development across

countries is the Human Development Index (HDI) compiled by the United Nations

Development Program (United Nations Human Development Program, 2018). The index

measures human capabilities across countries, and includes in its construction

indices of life expectancy, education, and gross national income per capita

(measured on a purchasing power basis). The index in each sample country for

2013 is reported in appendix, Table A1. The human development index is a

country-level negative predictor of family size as one would expect given that

human fertility typically declines with each of the three measures of human

development. Finally, Social Class is a negative predictor of family size

suggesting a positive connection between fertility and economic insecurity at

the individual level.

The

expansion of post-materialism on a global basis thus contributes to lower

global fertility rates and ultimately to the dampening of global population

growth. A slowing of population growth worldwide by itself will lead to slower

economic growth, lower throughput rates than otherwise for energy and

materials, and less harm to the global biosphere. Again, post-materialism is a

good deal for the environment. Note also that development is especially

important in reducing family size. Countries with a larger human development

index have smaller families and consequently lower fertility. Both

post-materialism and human development matter for reductions in human fertility

that lead to lower population growth and perhaps eventual population

reductions. Given that the life-time environmental impact of another person in

the developed world is many multiples of someone in a comparatively poor

country, reduction of family size among post-materialists in affluent societies

is especially important. Note also that post-materialists tend to have smaller

families while working-class materialists farther down the social class pecking

order tend to have larger families implying that a reduction in social

inequality could in turn decrease human fertility.

The

essential takeaway message of the ‘post-material silent revolution’ is this:

younger generations in economically and physically secure countries around the

world express values and pursue activities outside the arena of material

possessions more so than their older peers. The best experiences of their life

don’t require continuous additions to material affluence, and for them a low-

or even no-growth economy would be just fine as long as opportunities to earn a

minimum threshold income are available. Post-materialists also seem fine with

smaller families, less population growth, and a subsequent diminished need for

continuing economic expansion. Through generational replacement,

post-material values more prevalent among younger individuals will become more

extensive in the global population as a whole over time. In short, the growth

orientation of capitalism possesses little appeal to post-materialists,

especially if it is destructive of the global biosphere and harmful to cultural

and natural assets that support access to post-material experiences.

In

addition to being oriented to a less entropic form of living, post-materialists

exhibit support for the environment in terms of both their attitudes and

actions in the world. A long line of research demonstrates that the possession

of Inglehart post-material values around the world predicts individual support

for the environment, and, more specifically, for addressing the problem of

climate change (Booth, 2017). Such support extends as well to those individuals

who engage in post-material experience activities as suggested by the WVS

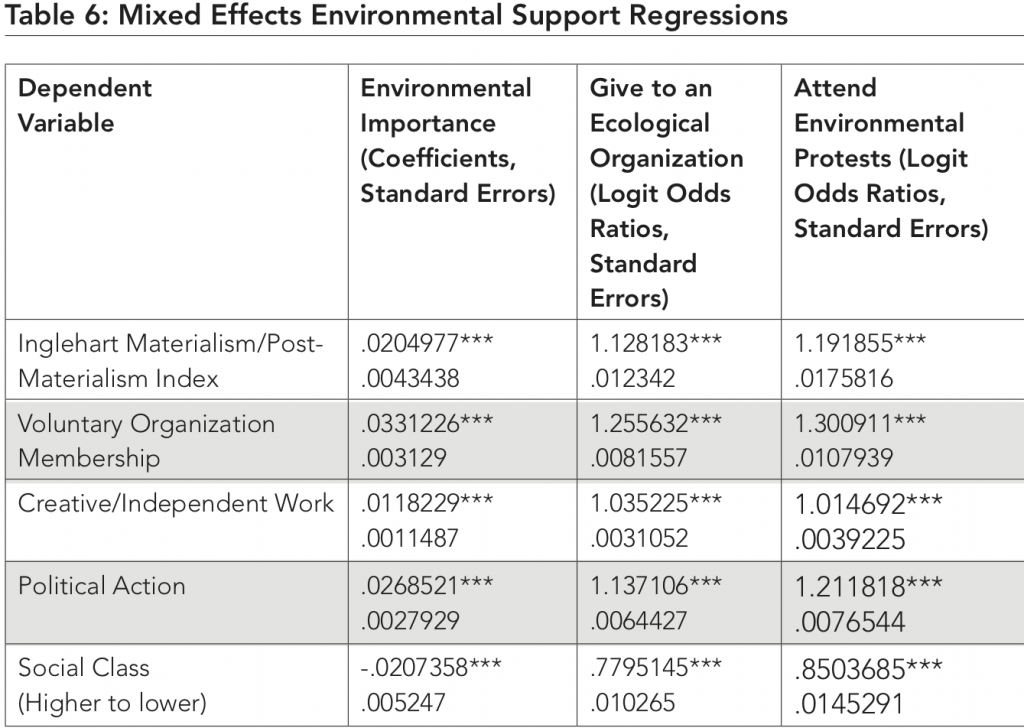

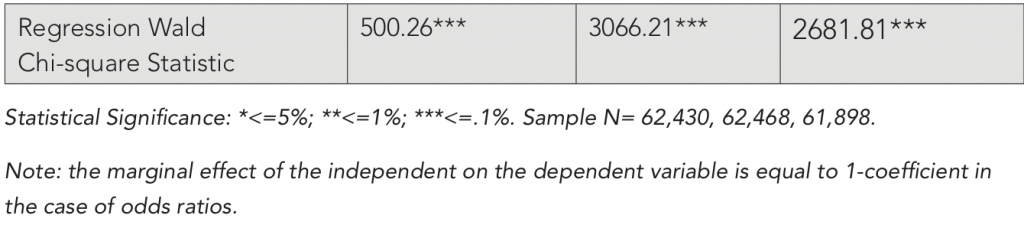

statistical analysis to follow in Table 6:

The

essential conclusions that follow from Table 6 are these: (1) Four separate

measures of post-materialism (Inglehart post-material values, voluntary

organization membership, creative and independent work, and political action)

positively and significantly predict each of three different measures of

individual support for the environment (the importance of doing something for

the environment, contributing to ecological organizations, and attending an

environmental demonstration); (2) Social Class (higher to lower) negatively

predicts support for the environment at significant levels. The dependent

variables, Give to An Ecological Organization and Attend Environmental

Protests, are both binary variables and require a logistical regression for

estimation. For the independent variables in the regression equations, if the

odds ratio is greater than one and statistically significant then the variable

has a positive effect on the dependent variable and if it is less than one and

significant it possesses a negative effect. To illustrate the meaning of the

odds-ratio consider the coefficients in the Attend Environmental Protests. The

odds ratio for Inglehart Post-Materialism equals 1.19 meaning that a 1 unit

increase in the Index will increase the probability of a typical individual

attending protests by 19 %. If we compare a materialist with an index equal to

0 and a post-materialist with an index equal to 5, then the odds are that such

a post-materialist will attend environmental protests will be (5 x 19=) 94 % greater

than the materialist. Clearly, post-materialism matters for engaging in

environmental actions. Similar calculations can be undertaken with the other

independent variable with similar results.

These

findings interestingly, and perhaps unsurprisingly, reveal a social class gap

in support for the environment between middle-class post-materialists and

working-class materialists. Moving down the social class ladder by a single

class results in a (100-85.0=) 15 % reduction in the odds of attending environmental

protests, for example. Working class individuals at the lower end of the social

class pecking order struggle to sustain a decent standard of living, a struggle

that is aggravated by increasing economic inequality in the most affluent

countries around the world and by economic disruptions such as the 2008 global

economic meltdown (Alvaredo, Chancel, Piketty, Saez, and Zucman, 2017; Saez,

2009; Stiglitz, 2010; Wisman, 2013). For this reason, members of the global

working class, many of whom suffer from economic insecurity, are more strongly

oriented than others to materialist goals and consequently place a lower

priority on support for the environment.

Conclusion

The

long-term trend towards post-materialism around the world fueled by

generational replacement is a good thing for the environment worldwide as it

takes the pressure off the growing demand for material possessions, fosters

more energy efficient and less entropic forms of living, reduces fertility and

population growth, and increases political support for protecting the global

biosphere. This trend supports the emergence of a green economy with

reduced rates of energy and materials throughput as a foundation for increasing

the health of the global biosphere.

Reducing

energy and materials throughput rates alone will not be enough to bring about

the climatic stability necessary to a healthy world environment (Jackson,

2017). This will require a decarbonization of the global energy system and a

worldwide ‘Green New Deal’ (Booth, 2020a; Sachs, 2019). Such decarbonization

has the special virtue of creating well-paid working-class jobs by replacing

capital-intensive fossil fuel energy with labor-intensive clean energy (Wei,

Patadia, and Kammen, 2010). Doing so will not only satisfy the political

demands for environmental improvement from politically active post-materialists

but will help bring working-class materialists on board the environmental

protection bandwagon by improving their immediate economic prospects and in the

longer term moving them upwards in the social class structure to the point

where post-materialism will become an attractive option for youths coming of

age in working-class families that have attained a middle-class material status

(Booth, 2020a). The social class divide between middle-class post-materialism

and working-class materialism may well be surmountable by way of a Green New

Deal that brings in its wake a healthier global biosphere.

Appendix

|

Table A1. Human Development Index (HDI Distribution Across 59

WVS Sample Countries, 2013)* |

||

|

Country |

Human Development Index |

Cumulative % |

|

Rwanda |

.503 |

1.80 |

|

Yemen |

.507 |

2.97 |

|

Zimbabwe |

.516 |

4.74 |

|

Nigeria |

.519 |

6.80 |

|

Pakistan |

.538 |

8.22 |

|

Ghana |

.577 |

10.04 |

|

India |

.607 |

11.90 |

|

Morocco |

.645 |

13.31 |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

.658 |

15.08 |

|

Iraq |

.666 |

16.49 |

|

South Africa |

.675 |

20.64 |

|

Palestine |

.679 |

21.81 |

|

Egypt |

.680 |

23.61 |

|

Philippines |

.685 |

25.02 |

|

Uzbekistan |

.690 |

26.78 |

|

Libya |

.707 |

29.29 |

|

Tunisia |

.723 |

30.70 |

|

Jordon |

.727 |

32.12 |

|

Thailand |

.728 |

33.53 |

|

China |

.729 |

36.23 |

|

Ecuador |

.734 |

37.64 |

|

Columbia |

.735 |

39.42 |

|

Peru |

.736 |

40.85 |

|

Armenia |

.742 |

42.14 |

|

Algeria and Ukraine |

.745 |

45.31 |

|

Brazil |

.748 |

47.06 |

|

Lebanon |

.751 |

48.47 |

|

Azerbaijan |

.752 |

49.65 |

|

Mexico |

.756 |

52.00 |

|

Georgia |

.757 |

53.42 |

|

Turkey |

.771 |

55.30 |

|

Trinidad |

.779 |

56.48 |

|

Malaysia |

.785 |

58.01 |

|

Kazakhstan |

.788 |

59.77 |

|

Kuwait |

.795 |

61.30 |

|

Uruguay |

.797 |

62.48 |

|

Romania |

.800 |

64.25 |

|

Belarus and Russia |

.804 |

68.99 |

|

Bahrain |

.807 |

70.40 |

|

Argentina |

.820 |

71.62 |

|

Chile |

.828 |

72.79 |

|

Poland |

.850 |

73.93 |

|

Cyprus |

.853 |

75.10 |

|

Qatar |

.854 |

76.35 |

|

Estonia |

.862 |

78.15 |

|

Spain |

.875 |

79.55 |

|

Slovenia |

.885 |

80.81 |

|

South Korea |

.893 |

82.22 |

|

Japan |

.899 |

85.09 |

|

New Zealand |

.907 |

86.08 |

|

Sweden |

.912 |

87.50 |

|

Hong Kong |

.915 |

88.68 |

|

United States |

.916 |

91.30 |

|

Netherlands and Singapore |

.923 |

95.86 |

|

Germany |

.928 |

98.26 |

|

Australia |

.931 |

100.00 |

|

*Taiwan data is unavailable. |

||

References

Alper,

N. O., and Wassall, G. H., 2006. Artists’ careers and their labor markets. In:

V. A. Ginsburgh and D. Throsby, eds. 2006. Handbook of the economics of art and culture.

Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Alvaredo,

F., Chancel, L., Piketty, T., Saez, E., and Zucman, G., 2017. Global inequality

dynamics: new findings from The World Wealth and Income Database. American Economic Review, 107(5), pp.404-409.

Birch,

E. L. 2005. Who lIves downtown? In: A. Berube, B. Katz, and R. E. Lang, eds.

2005. Redefining urban and suburban

America: evidence from Census 2000. Washington DC: Brookings Institution

Press. pp.29-49.

Birch,

E. L., 2009. Downtown in the “new American city”. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science,

626(1), pp.134-153.

Booth,

D. E., 2017. Postmaterialism and support for the environment in the United

States. Society and Natural Resources,

30(11), pp.1404-1420.

Booth,

D. E., 2018a. Postmaterial experience economics. Journal of Human Values, 24(2), pp.1-18.

Booth,

D. E., 2018b. Postmaterial experience economics, population, and environmental

sustainability. The Journal of Population and

Sustainability, 2(2), pp.33-50.

Booth,

D. E., 2020a. Achieving a post-growth green economy. J The Journal of Population and

Sustainability, 5(1), pp.57-75.

Booth,

D. E., 2020b. Postmaterialism’s social-class divide: experiences and life

satisfaction. Journal of Human Values,

forthcoming.

Brombach,

K., Jessen, J., Siedentop, S., and Zakrzewski, P., 2017. Demographic patterns

of reurbanisation and housing in metropolitan regions in the U.S. and Germany. Comparative Population Studies, 42, pp.281-317.

Chang,

C. C., and Chen, T. S., 2013. Idealism versus reality: empirical test of

postmaterialism in China and Taiwan. Issues and Studies,

49(2), pp.63-102.

Harari,

Y. N., 2015. Sapiens: a brief history of

humankind. New York: Harper Collins.

Inglehart,

R. F., 1971. The silent revolution in Europe: intergenerational change in

post-industrial societies. American Political Science

Review, 65(4), pp.991-1017.

Inglehart,

R. F., 2008. Changing values among western publics from 1970 to 2006. West European Politics, 31(1-2), pp.130-146.

Inglehart,

R. F., and Abramson, P. R., 1994. Economic security and value change. American Political Science Review,

88(2), pp.336-354.

Inglehart,

R. F., and Abramson, P. R., 1999. Measuring postmaterialism. American Political Science Review,

93(3), pp.665-667.

Inglehart,

R. F., and Norris, P., 2016. Trump, Brexit, and the rise of

populism: economic have-nots and cultural backlash. HKS Working Paper No.

RWP16-026. [pdf] Available at:

https://research.hks.harvard.edu/publications/workingpapers/citation.aspx?PubId=11325.

[Accessed 28 June 2021].

Inglehart,

R. F., and Welzel, C., 2005. Modernization, cultural change,

and democracy: the human development sequence. New

York: Cambridge University Press.

Jackson,

T., 2017. Prosperity without growth:

foundations for the economy of tomorrow. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Jackson,

T., 2019. The post-growth challenge: secular stagnation, inequality and the

limits to growth. Ecological Economics,

156, pp.236-246.

Lloyd,

R., 2002. Neo-bohemia: art and neighborhood redevelopment in Chicago. Journal of Urban Affairs, 24,

pp.517-532.

Markusen,

A., 2006. Urban development and the politics of a creative class: evidence from

a study of artists. Environment and Planning, 38, 1921-1940.

Markusen,

A., and Gadwa, A. 2010. Arts and culture in urban or regional planning: a

review and research agenda. Journal of Planning Education

and Research, 29(3), pp.379-391.

Markusen,

A., and Schrock, G., 2006. The artistic dividend: urban artistic specialisation

and economic development implications. Urban Studies,

43(10), 1661-1686.

New

York City, 2007. Inventory of New York City

greenhouse gas emissions.[pdf] Available at:

http://www.nyc.gov/html/planyc/downloads/pdf/publications/greenhousegas_2007.pdf

[Accessed 28 June 2021].

Newman,

P., and Kenworthy, J. R., 1999. Sustainability and cities:

overcoming automobile dependency. Washington DC: Island

Press.

Newman,

P., and Kenworthy, J. R., 2015. The end of automobile

dependence: how cities are moving beyond car-based planning.

Washington DC: Island Press.

Norris,

P., and Inglehart, R., 2019. Cultural backlash: Trump,

Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Polzin,

S. E., Chu, X., and Godrey, J., 2014. The impact of Millennials’ travel

behavior on future personal vehicle travel. Energy Strategy Reviews, 5, pp.59-65.

Rogers,

E., and Stephenson, R., 2018. Examining temporal shifts in the proximate

determinants of fertility in low- and middle-income countries. Journal of Biosocial Science, 50(4), pp.551-568.

Sachs,

J. 2019. Getting to a carbon-free economy. The American Prospect.[online] Available at:

https://prospect.org/greennewdeal/getting-to-a-carbon-free-economy/ [Accessed

28 June 2021].

Saez,

E., 2009. Striking it richer: the

evolution of top incomes in the United States (update with 2007 estimates).

[pdf] UC Berkeley Working Paper Series. Available at: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8dp1f91x

[Accessed 28 June 2021].

Stata

Corporation, 2015. STATA statistics and data analysis, 14.0. [online] College

Stations, Texas: Stata Corporation. Available at: https://www.stata.com

[Accessed 28 June 2021].

Stiglitz,

J. E., 2010. Freefall: America, free

markets, and the sinking of the world economy. New

York: W.W. Norton.

Tsai,

Y.-H., 2005. Quantifying urban form: compactness versus ‘sprawl’. Urban Studies, 42(1), pp.141-161.

United

Nations Human Development Program, 2018. Human development reports. [online] Available at:

http://hdr.undp.org/en/humandev [Accessed 28 June 2021].

Victor,

P. A., 2008. Managing without growth: slower

by design, not disaster. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Wei,

M., Patadia, S., and Kammen, D. M., 2010. Putting renewables and energy

efficiency to work: how many jobs can the clean energy industry generate in the

U.S.? Energy Policy, 38,

pp.919-931.

Welzel,

C., Inglehart, R. F., and Deutsch, F., 2005. Social capital, voluntary

associations and collective action: which aspects of social capital have the

greatest ‘civic’ payoff? Journal of Civil Society,

1(2), pp.121-146.

World

Bank, 2019a. Fertility rate, total (births

per woman). [online] Available at:

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN/ [Accessed 28 June 2021].

World

Bank, 2019b. Population growth (annual %).

[online] Available at:

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.GROW?end=2011&start=1961

[Accessed 28 June 2021].

World

Values Survey Association, 2015. World values survey, wave

1-wave 6.[online] Available at: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org

[Accessed 28 June 2021].

World

Values Survey Association, 2020. World values survey, wave 7. [online] Available at:

http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSOnline.jsp [Accessed 28 June 2021].